Charleston, West Virginia

Charleston | |

|---|---|

Downtown Charleston | |

| Nickname: Charlie West[1] | |

Interactive map of Charleston | |

| Coordinates: 38°20′59.35″N 81°37′57.44″W / 38.3498194°N 81.6326222°W | |

| Country | United States |

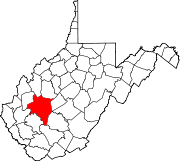

| State | West Virginia |

| County | Kanawha |

| Founded | 1788 |

| Incorporated | 1794 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Strong-Mayor Government |

| • Mayor | Amy Shuler Goodwin (D) |

| • City Council | Members list |

| • City Manager | Benjamin Mishoe, Esq. |

| Area | |

• City | 32.535 sq mi (84.265 km2) |

| • Land | 31.397 sq mi (81.317 km2) |

| • Water | 1.138 sq mi (2.948 km2) |

| Elevation | 597 ft (182 m) |

| Population | |

• City | 48,864 |

• Estimate (2023)[6] | 46,838 |

| • Rank | US: 863rd WV: 1st |

| • Density | 1,491.83/sq mi (575.99/km2) |

| • Urban | 140,958 (US: 248th) |

| • Metro | 203,164 (US: 228th) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes | ZIP Codes[7] |

| Area code(s) | 304 and 681 |

| FIPS code | 54-14600 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1558347[4] |

| Highways | US-60, I-64, I-77, US-119, and SR-214 |

| Sales tax | 7.0%[8] |

| Website | charlestonwv.gov |

Charleston is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of West Virginia and the seat of Kanawha County.[9] It is at the confluence of the Elk and Kanawha rivers. The population was 48,864 at the 2020 census.[5] According to 2023 census estimates, the city has a population of 46,838.[6] The Charleston metropolitan area had 203,164 residents in 2023.

In 1773, William Morris built the first permanent settlement in the Kanawha Valley, Fort Morris. It was built about 20 miles upstream of Charleston at the confluence of Kellys Creek, near the burned ruins of Walter Kelly's cabin, before Lord Dunmore's War, and was used extensively during the American Revolution.[10] In 1794, the town of Charleston was incorporated by the Virginia House of Delegates with the trustees being William Morris, Leonard Morris, and Daniel Boone.[11] Early industries important to Charleston included salt and the first natural gas well.[12] Later, coal became central to economic prosperity in the city and the surrounding area. Today, trade, utilities, government, medicine, and education play central roles in the city's economy.

Charleston is the home of the Charleston Dirty Birds of the Atlantic League of Professional Baseball and the annual 15-mile (24 km) Charleston Distance Run. Yeager Airport and the University of Charleston are in the city. West Virginia State University is in the area, as are West Virginia University and Marshall University satellite campuses.

History

[edit]Establishment

[edit]

After the American Revolutionary War, pioneers began making their way out from the early settlements. Many slowly migrated into western Virginia. Capitalizing on its many resources made Charleston an important part of Virginia and West Virginia history. It is the state's capital and most populous city.

Charleston's history goes back to the 18th century. Thomas Bullitt was deeded 1,250 acres (5 km2) of land near the mouth of the Elk River in 1773. It was inherited by his brother, Cuthbert Bullitt, upon his death in 1778, and sold to Colonel George Clendenin in 1786. Clendenin and his company of Virginia Rangers built the first permanent settlement, Fort Lee, in 1787. This structure occupied the area that is now the intersection of Brooks Street and Kanawha Boulevard. Historical conjecture indicates that Charleston is named after Clendenin's father, Charles. In 1794, the Virginia General Assembly officially established Charlestown.[13] On the 40 acres (160,000 m2) that made up the town in 1794, 35 people inhabited seven houses.

Charleston is part of Kanawha County. The origin of the word Kanawha (pronounced "Ka-NAH-wah"), Ka(h)nawha, derives from the region's Iroquoian dialects meaning "water way" or "Canoe Way", implying the metaphor "transport way". It was and is the name of the river that flows through Charleston. The "hard H" sound soon dropped out as various European arrivals developed West Virginia.[14] The phrase has been a matter of register. A two-story jail was the first county structure to be built, with the first floor dug into the bank of the Kanawha River.

In 1791, Daniel Boone, who was commissioned a lieutenant colonel of the Kanawha County militia, was elected to serve in the Virginia House of Delegates. Boone supposedly walked all the way to Richmond, the state capital. He served alongside Major William Morris Jr, representing Kanawha.

19th century growth

[edit]

By the early 19th century, salt brines were discovered along the Kanawha River, and the first salt well was drilled in 1806.[15] This created great economic growth in the area. By 1808, 1,250 pounds of salt were being produced daily, and the Farmers' Repository newspaper began publication.[16] An area adjacent to Charleston, Kanawha Salines (now Malden), became the world's top salt producer. Brine was heated over open flames, causing the water to evaporate and leaving a residue of salt crystals. Much of the work was done by enslaved peoples. Historian Cyrus Forman estimated that at the height of production as many as 3,000 slaves worked at more than 60 salt furnaces, which operated 24 hours a day, seven days a week.[17] The Holly Grove Mansion was established during this period.[15] In 1818, the Kanawha Salt Company, the first trust in the United States, went into operation. In the same year, "Charlestown" was shortened to "Charleston" to avoid confusion with another Charles Town in eastern West Virginia, named after George Washington's brother, Charles Washington.[18] A lyceum was established around 1841.[19]

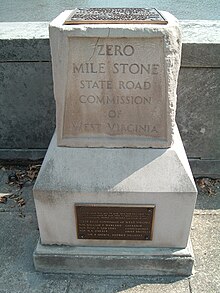

Captain James Wilson, while drilling for salt, struck the first natural gas well in 1815. It was drilled at the site that is now the junction of Brooks Street and Kanawha Boulevard (near the present-day state capitol complex). In 1817, coal was first discovered and gradually became used as the fuel for the salt works. The Kanawha salt industry declined in importance after 1861, until the onset of World War I brought a demand for chemical products. The chemicals needed were chlorine and sodium hydroxide, which could be made from salt brine.

The town continued to grow until the Civil War began in 1861. After the Virginia Secession Convention of 1861 and a referendum, Virginia seceded from the Union. But Charleston, like much of western Virginia, was divided in loyalty between the Union and the Confederacy. On September 13, 1862, the Union and Confederate armies clashed in the Battle of Charleston. The Confederates won, but could not hold the area for long. Union soldiers returned in force six weeks later and retook the city.[15] Charleston remained under Union control for the remainder of the war.

In addition to the dispute over slavery, the North wanted to separate West Virginia from the rest of the state for economic reasons. The heavy industries in the North, particularly the steel business of the upper Ohio River region, depended on coal from western Virginia mines. Federal units from Ohio marched into western Virginia early in the war solely to capture the mines and control transportation in the area.[citation needed] The Wheeling Convention of 1861 declared the Ordinance of Succession, and the Confederate state government in Richmond, illegal and void, and formed the Unionist Restored Government of Virginia. The Restored Government and the United States Congress approved the formation of the state of West Virginia, which was admitted on June 20, 1863, as the 35th state, and the Restored Government of Virginia moved to Alexandria.[18]

Choosing the state capital proved difficult. For several years, the capital moved between Wheeling and Charleston.[20] In 1877, the citizens voted on a permanent location. Charleston received 41,243 votes, Clarksburg 29,442, and Martinsburg 8,046; Wheeling was not considered. Eight years later the state capitol opened in Charleston.[15]

The West Virginia Historical and Antiquarian Society was headquartered in Charleston in 1890.[21][22] In 1891, the West Virginia Colored Institute, now known as West Virginia State University, was established. The next year, Capitol City Commercial College was founded.[23] Charleston's Basilica of the Co-Cathedral of the Sacred Heart was completed in 1897.

20th century

[edit]

Charleston became the center of state government. Natural resources, such as coal and natural gas, along with railroad expansion, also contributed to growth. New industries such as chemical, glass, timber and steel migrated to the state, attracted by the area's natural resources. The city established a chamber of commerce in 1900.[23] There was a large amount of new construction in Charleston during this period. A number of those buildings, including churches and office buildings, still stand in the heart of downtown along and bordering Capitol Street. The State Bureau of Archives and History was established in 1905, and the Charleston Public Library was established in 1909.[21][24]

The city's first chemical manufacturer began operation in 1913.[15] Three years later, the Libbey-Owens-Ford glass manufactory was built,[25] as well as Charleston High School. Another large manufacturer, Owens Bottle Company, opened in 1917. Charleston City Hall was built in 1921. In the same year, a fire at the capitol building resulted in a new, hastily built structure being opened, but it too burned down in 1927. A Capitol Building Commission, created by the legislature in 1921, authorized construction of the present capitol. Architect Cass Gilbert designed the buff-colored Indiana limestone structure in the Italian Renaissance style, with a final cost of just under $10 million. After the three stages of construction were completed, Governor William G. Conley dedicated the West Virginia State Capitol on June 20, 1932. Charleston Municipal Airport was established in 1909.[18] In 1934, the city library expanded to become the Kanawha County Public Library system.[24] In 1935, Morris Harvey College relocated to Charleston from Barboursville, West Virginia.[26]

Charleston Municipal Auditorium was completed in 1939.[15] During World War II, the first and largest styrene-butadiene plant in the U.S. opened in nearby Institute, providing a replacement for rubber to the war effort.[27] After the war ended, Charleston was on the brink of some significant construction. One of the first during this period was Kanawha Airport (now Yeager Airport, named after General Chuck Yeager). Built in 1947, the construction encompassed clearing 360 acres (1.5 km2) on three mountaintops and moving more than nine million cubic yards of earth.[13] Kanawha Boulevard, a riverfront four-lane road, was also built in the early 1940s.[15] The Charleston Civic Center opened in 1959.

Charleston began to be integrated into the Interstate Highway System in the 1960s when three major interstate systems—I-64, I-77 and I-79 were designated, all converging in Charleston. In 1961, the Kanawha River flooded much of the lower-lying parts of Charleston.[18] In 1973, Morris Harvey College was renamed to be the University of Charleston.[26]

In 1983, the Charleston Town Center opened its doors downtown. It was the largest urban-based mall east of the Mississippi River, featuring three stories of shops and eateries. Downtown revitalization began in earnest in the late 1980s. Funds were set aside for streetscaping as Capitol and Quarrier streets saw new building facades, trees along the streets, and brick walkways installed. For a time, the opening of the Charleston Town Center Mall had a somewhat negative impact on the main streets of downtown Charleston, as many businesses closed and relocated into the mall. Also in 1983, West Virginia Public Radio launched a live-performance radio program statewide called Mountain Stage.[28] What began as a live, monthly statewide broadcast went on to national distribution in 1986 through National Public Radio and around the world on the Voice of America satellite service.

The Robert C. Byrd Federal Building, Haddad Riverfront Park, and Capitol Market are just a few of the new developments that have helped growth in the downtown area during the 1990s. Charleston launched its city website in 1998.[29][30]

21st century

[edit]2003 marked the opening of the Clay Center for the Arts & Sciences.[13] The center includes the Maier Foundation Performance Hall, the Walker Theatre, the Avampato Discovery Museum and the Juliet Art Museum. Also on site is the ElectricSky Theater, a 175-seat combination planetarium and dome-screen cinema. Movies shown at the theatre include educational large format (70 mm) presentations and are often seen in similar Omnimax theatres. Planetarium shows are staged as a combination of pre-recorded and live presentations. The West Virginia Music Hall of Fame was established in 2005.[31]

Many festivals and events were also incorporated into the calendar, including Multifest, Vandalia Festival, a July 4 celebration with fireworks at Haddad Riverfront Park, and the already popular Sternwheel Regatta, which was founded in 1970, provided a festive atmosphere for residents to enjoy. In 2005 FestivALL Charleston was established and has grown into a ten-day festival offering a variety of performances, events and exhibits in music, dance, theatre, visual arts and other entertainments.

Charleston has one central agency for its economic development efforts, the Charleston Area Alliance. The Alliance works with local public officials and the private sector to build the economy of the region and revitalize its downtown. Charleston also has an economic and community development organization focused on the East End and West Side urban neighborhood business districts, Charleston Main Streets.

Geography

[edit]

Charleston is in west-central Kanawha County at 38°20′59.35″N 81°37′57.44″W / 38.3498194°N 81.6326222°W (38.3498195, -81.6326235). The elevation is 597 feet (182 m) above sea level.[4] It lies within the ecoregion of the Western Allegheny Plateau.[32]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has an area of 32.535 square miles (84.27 km2), of which 31.397 square miles (81.32 km2) is land and 1.138 square miles (2.95 km2) is water.[3]

The city lies at the intersection of Interstates 79, 77, 64, and also where the Kanawha and Elk rivers meet. Charleston is about 117 miles (188 km) southeast of Chillicothe, Ohio, 315 miles (507 km) west of Richmond, Virginia, 228 miles (367 km) southwest of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, 247 miles (398 km) east of Louisville, Kentucky, and 264 miles (425 km) north of Charlotte, North Carolina.

Neighborhoods

[edit]

The following are neighborhoods and communities within the city limits:

- Charleston Heights (Westmoreland/Hillsdale)

- East End

- Edgewood

- Elk City

- Forest Hills

- Fort Hill

- Kanawha City

- Louden Heights

- North Charleston

- Riverview

- Shadowlawn

- South Park

- South Hills

- South Ruffner

- West Side

Climate

[edit]Charleston has a four-season humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa) with continental climate (Dfa) elements.[33] Especially in winter, Charleston's average temperatures are warmer than the rest of the state, due to the city being west of the higher elevations. Spring is the most unpredictable season, and spring-like weather usually arrives in late March or early April. From the beginning of March through early May, temperatures can vary considerably and it is not unusual at this time for day-to-day temperature fluctuations to exceed 20 °F (11 °C). Temperatures warm up considerably in late May, with warm summer-like days. Summer is warm to hot, with 23 days of highs at or above 90 °F (32 °C),[34] sometimes reaching 95 °F (35 °C), often accompanied by high humidity. Autumn features crisp evenings that warm quickly to mild to warm afternoons. Winters are chilly, with a January daily average of 34.4 °F (1.3 °C), and with a mean of 16 days with maxima at or below the freezing mark.[34] Snowfall generally occurs from late November to early April, with the heaviest period being January and February. However, major snowstorms of more than 10 inches (25 cm) are rare. The area averages about 3.5 inches (89 mm) of precipitation each month. Thunderstorms are frequent during the late spring and throughout the summer, and occasionally they can be quite severe, producing the rare tornado.

Record temperatures have ranged from −17 °F (−27 °C) on December 30, 1917, to 108 °F (42 °C) on August 6, 1918, and July 4, 1931.[34] Decades can pass between temperatures of 100 °F (37.8 °C) or hotter, and the last such instance was July 8, 2012.[34] The record cold maximum is 4 °F (−16 °C) on December 22, 1989 (during the December 1989 United States cold wave). The record warm minimum is 84 °F (29 °C) on July 29, 1924.[34] The hardiness zone is 7a.

| Climate data for Charleston, West Virginia (Yeager Airport), 1991–2020 normals,[a] extremes 1892–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 81 (27) |

81 (27) |

92 (33) |

96 (36) |

98 (37) |

105 (41) |

108 (42) |

108 (42) |

104 (40) |

96 (36) |

87 (31) |

80 (27) |

108 (42) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 68.2 (20.1) |

70.6 (21.4) |

79.1 (26.2) |

86.8 (30.4) |

88.8 (31.6) |

92.0 (33.3) |

93.9 (34.4) |

93.1 (33.9) |

90.1 (32.3) |

84.5 (29.2) |

77.3 (25.2) |

69.1 (20.6) |

95.3 (35.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 43.9 (6.6) |

47.8 (8.8) |

56.8 (13.8) |

69.4 (20.8) |

76.2 (24.6) |

83.1 (28.4) |

86.0 (30.0) |

85.2 (29.6) |

79.5 (26.4) |

68.7 (20.4) |

57.3 (14.1) |

47.5 (8.6) |

66.8 (19.3) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 35.0 (1.7) |

38.2 (3.4) |

46.0 (7.8) |

56.9 (13.8) |

64.7 (18.2) |

72.3 (22.4) |

75.8 (24.3) |

74.6 (23.7) |

68.3 (20.2) |

57.0 (13.9) |

46.4 (8.0) |

38.7 (3.7) |

56.2 (13.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 26.1 (−3.3) |

28.6 (−1.9) |

35.1 (1.7) |

44.5 (6.9) |

53.2 (11.8) |

61.5 (16.4) |

65.5 (18.6) |

64.1 (17.8) |

57.1 (13.9) |

45.3 (7.4) |

35.6 (2.0) |

29.9 (−1.2) |

45.5 (7.5) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 5.5 (−14.7) |

9.9 (−12.3) |

17.0 (−8.3) |

27.6 (−2.4) |

37.1 (2.8) |

48.8 (9.3) |

55.7 (13.2) |

54.1 (12.3) |

43.3 (6.3) |

30.4 (−0.9) |

20.6 (−6.3) |

12.9 (−10.6) |

2.3 (−16.5) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −16 (−27) |

−12 (−24) |

−5 (−21) |

18 (−8) |

26 (−3) |

33 (1) |

46 (8) |

41 (5) |

32 (0) |

17 (−8) |

6 (−14) |

−17 (−27) |

−17 (−27) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.27 (83) |

3.36 (85) |

4.14 (105) |

3.56 (90) |

4.93 (125) |

4.72 (120) |

5.38 (137) |

3.75 (95) |

3.46 (88) |

2.91 (74) |

3.20 (81) |

3.56 (90) |

46.24 (1,174) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 10.3 (26) |

7.7 (20) |

5.9 (15) |

0.5 (1.3) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.6 (1.5) |

1.5 (3.8) |

5.0 (13) |

31.5 (80) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 14.8 | 13.7 | 14.8 | 13.4 | 14.1 | 12.5 | 12.8 | 10.6 | 9.0 | 10.1 | 11.0 | 14.2 | 151.0 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 7.6 | 6.2 | 3.9 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.5 | 4.1 | 23.9 |

| Source: NOAA[34][35] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 1,050 | — | |

| 1860 | 1,520 | 44.8% | |

| 1870 | 3,162 | 108.0% | |

| 1880 | 4,192 | 32.6% | |

| 1890 | 6,742 | 60.8% | |

| 1900 | 11,099 | 64.6% | |

| 1910 | 22,996 | 107.2% | |

| 1920 | 39,608 | 72.2% | |

| 1930 | 60,408 | 52.5% | |

| 1940 | 67,914 | 12.4% | |

| 1950 | 73,501 | 8.2% | |

| 1960 | 85,796 | 16.7% | |

| 1970 | 71,505 | −16.7% | |

| 1980 | 63,968 | −10.5% | |

| 1990 | 57,287 | −10.4% | |

| 2000 | 53,421 | −6.7% | |

| 2010 | 51,400 | −3.8% | |

| 2020 | 48,864 | −4.9% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 46,838 | [6] | −4.1% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[36] 2020 Census[5] | |||

2020 census

[edit]| Race / ethnicity (NH = non-Hispanic) | Pop. 2000[37] | Pop. 2010[38] | Pop. 2020[39] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 42,810 | 39,900 | 36,216 | 74.1% | ||

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 7,998 | 7,867 | 7,136 | 14.6% | ||

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 120 | 116 | 115 | 0.2% | ||

| Asian alone (NH) | 974 | 1,178 | 1,254 | 2.6% | ||

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 12 | 17 | 20 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Other race alone (NH) | 88 | 80 | 288 | 0.6% | ||

| Mixed race or multiracial (NH) | 987 | 1,548 | 2,866 | 5.9% | ||

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 432 | 694 | 969 | 0.8% | 1.4% | 2.0% |

| Total | 53,421 | 51,400 | 48,864 | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

As of the 2020 census, there were 48,864 people, 22,082 households, and 11,685 families residing in the city.[40] The population density was 1,551.2 inhabitants per square mile (598.9/km2). There were 25,766 housing units. The racial makeup of the city was 74.7% White, 14.8% African American, 0.3% Native American, 2.6% Asian, 0.0% Pacific Islander, 1.1% from some other races and 6.6% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino people of any race were 2.0% of the population.[41]

There were 22,082 households, of which 36.8% were married couples living together, 34.7% had a female householder with no spouse present, 22% had a male householder with no spouse present. The average household and family size was 2.94. The median age in the city was 41.7 years with 18.9% of the population under 18. The median income for a household in the city was $54,101 and the poverty rate was 17.5%.

The median age in the city was 36.0. 27.6% of residents were under the age of 18; 7.6% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 26.9% were between the ages of 25 and 44; 21.9% were between the ages of 45 and 64; and 13.9% were 65 and older. The gender makeup of the city was 50.9% male and 49.1% female.

2022 American Community Survey (ACS)

[edit]There are 21,746 households accounted for in the 2022 ACS, with an average of 2.12 persons per household. The city's a median gross rent is $870 in the 2022 ACS. The 2022 ACS reports a median household income of $58,902, with 60.8% of households are owner occupied. 17.0% of the city's population lives at or below the poverty line (down from previous ACS surveys). The city boasts a 56.6% employment rate, with 43.2% of the population holding a bachelor's degree or higher and 92.1% holding a high school diploma.[42]

The top nine reported ancestries (people were allowed to report up to two ancestries, thus the figures will generally add to more than 100%) were English (15.8%), German (13.5%), Irish (11.7%), Italian (3.9%), Scottish (2.3%), Subsaharan African (1.7%), French (except Basque) (1.2%), Polish (1.1%), and Norwegian (0.5%).

The median age in the city was 42.2 years.

2010 census

[edit]As of the 2010 census, there were 51,400 people, 23,453 households, and 12,587 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,630.7 inhabitants per square mile (629.6/km2). There were 26,205 housing units at an average density of 831.4 inhabitants per square mile (321.0/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 78.4% White, 15.5% African American, 0.2% Native American, 2.3% Asian, 0.3% from other races, and 3.2% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino people of any race were 1.4% of the population.

There were 23,453 households, of which 24.6% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 35.6% were married couples living together, 14.1% had a female householder with no husband present, 3.9% had a male householder with no wife present, and 46.3% were non-families. 39.4% of all households were made up of individuals, and 13.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.11 and the average family size was 2.83.

The median age in the city was 41.7 years. 20.1% of residents were under the age of 18; 9% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 24.9% were from 25 to 44; 29.9% were from 45 to 64; and 16.1% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 47.6% male and 52.4% female.

2000 census

[edit]As of the 2000 census, there were 53,421 people, 24,505 households, and 13,624 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,690.4 inhabitants per square mile (652.7/km2). There were 27,131 housing units at an average density of 858.5 inhabitants per square mile (331.5/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 80.63% White, 15.07% Black or African American, 0.24% Native American, 1.83% Asian, 0.03% Pacific Islander, 0.30% from other races, and 1.91% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino people of any race were 0.81% of the population.

The five most common ancestries were German (12.4%), English (11.6%), American (11.4%), Irish (10.6%), and Italian (3.9%).

There were 24,505 households, out of which 23.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 38.9% were married couples living together, 13.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 44.4% were non-families. 38.9% of all households were made up of individuals, and 14.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.11 and the average family size was 2.82.

The age distribution was 20.7% under 18, 8.4% from 18 to 24, 27.9% from 25 to 44, 25.3% from 45 to 64, and 17.6% who were 65 or older. The median age was 41 years. For every 100 females there were 87.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 83.7 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $34,009, and the median income for a family was $47,975. Males had a median income of $38,257 versus $26,671 for females. The per capita income for the city was $26,017. About 12.7% of families and 16.7% of the population were below the poverty line, including 24.5% of those under age 18 and 11.3% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

[edit]

The City of Charleston recognizes the Charleston Area Alliance as its economic development organization.[43] Notable companies headquartered in the Charleston area include Appalachian Power, owned by American Electric Power[44] of Columbus, Ohio; Charleston Gazette, Gestamp, Tudor's Biscuit World and United Bank.

Notable companies founded in Charleston include Shoney's restaurants and Heck's / L.A. Joe discount department stores.

Culture

[edit]Annual events and fairs

[edit]

Charleston is home to numerous annual events and fairs that take place from the banks of the Kanawha River to the capitol grounds.

The West Virginia Dance Festival, held between April 25 and 30, features dance students from across the state that attend classes and workshops in ballet, jazz, and modern dance. At the finale, the students give free public performances at the West Virginia State Theatre.

Symphony Sunday, held annually since 1982, usually the first weekend in June, is a full day of music, food, and family fun culminating in a free performance by the West Virginia Symphony Orchestra and a fireworks display. Throughout the day, local community dance and music ensembles perform. Ensembles that perform on Symphony Sunday include the Kanawha Valley Ringers, the West Virginia Kickers, the Charleston Metro Band, the West Virginia Youth Symphony, the Mountain State Brass Band, and the Kanawha Valley Community Band. The now-defunct Charleston Neophonic Orchestra also performed at the event.[45]

The NPR program Mountain Stage was founded in Charleston in 1983. The live performance music program, produced by West Virginia Public Broadcasting and heard on the Voice of America and via NPR Music, records episodes at the Culture Center Theater on the West Virginia State Capitol grounds.

Twice a year, in late April and early November, the West Virginia International Film Festival occurs,[46] at which many domestic and international films are shown, including full-length feature films, shorts, documentaries, animation, and student films.

Charleston hosts the annual Gazette-Mail Kanawha County Majorette and Band Festival for the eight public high schools in Kanawha County. The festival began in 1947 and has continued on as an annual tradition. It is held at the University of Charleston Stadium at Laidley Field in downtown Charleston. It is the state's oldest music festival.

On Memorial Day weekend, the Vandalia Gathering[47] is held on the state capitol grounds. Thousands of visitors each year enjoy traditional music, art, dance, stories, crafts, and food that stems from West Virginia's mountain culture.

Since 2005, FestivALL[48] has provided the Charleston area with cultural and artistic events beginning on June 20 (West Virginia Day) and including dance, theater, and music. FestivALL provides local artists a valuable chance to display their works and help get others interested in, and involved with, the local artistic community. Highlights include an art fair on Capitol Street and local bands playing live music at stages set up throughout downtown, as well as a wine and jazz festival on the campus of the University of Charleston featuring local and nationally known jazz artists and showcasing the products of West Virginia vineyards.

The Charleston Sternwheel Regatta is an annual river festival held on the Kanawha Boulevard by Haddad Riverfront Park on the Kanawha River. Founded in 1970, it was originally held during Labor Day weekend each year until its discontinuation in 2008, but after its revival in 2022, it is now held during Independence Day weekend. The event has carnival-style rides and attractions and live music from local and nationally known bands.[citation needed]

Historical structures and museums

[edit]

Charleston has several older buildings in various architectural styles. About 50 places in Charleston are on the National Register of Historic Places.[49] A segment of the East End consisting of several blocks of Virginia and Quarrier Streets, encompassing an area of nearly a full square mile, has been officially designated as a historical neighborhood. The neighborhood has many houses dating from the late 19th and early 20th century as well as a few art deco style apartment buildings dating from the 1920s and early 30s.

Downtown Charleston is home to several commercial buildings between 80 and 115 years old, including the Security Building (corner of Virginia and Capitol Street), 405 Capitol Street (the former Daniel Boone Hotel), the Union Building (at the southern end of Capitol Street), the Kanawha County Courthouse, the Public Library (corner of Capitol and Quarrier Streets), and the Masonic Temple (corner of Virginia and Dickenson Street). Also of note are several historic churches grouped closely together in a neighborhood just east of downtown; Basilica of the Co-Cathedral of the Sacred Heart (one of the two cathedrals of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Wheeling-Charleston), First Presbyterian Church, Kanawha United Presbyterian Church, St. John's Episcopal Church, Charleston Baptist Temple, St. Paul's Evangelical Lutheran Church, and Christ Church United Methodist.

Other historic buildings can be found throughout the city, particularly in the broader East End, the West Side, and Kanawha City. They include the Avampato Discovery Museum (now part of the Clay Center for the Arts & Sciences), Sunrise Museum, (now part of the Clay Center for the Arts & Sciences), West Virginia State Museum, St. George Orthodox Cathedral, St. Marks United Methodist Church, the Capitol Theater, and the Woman's Club of Charleston.[citation needed]

Retail

[edit]In 1983, the Charleston Town Center became the largest downtown mall east of the Mississippi River.[50] It is a three-story shopping and dining facility, formerly with 130 specialty stores; 31 remain open. The closure of Macy's in 2019 made J.C. Penney the sole remaining commercial anchor pad in the mall after Sears closed in 2017. The fourth and final anchor pad is a branch of Encova Insurance; it was occupied by various other insurance companies after Montgomery Ward left the mall in 2000. In 2021, it was announced that Hull Group, based in Augusta GA, will add the Town Center to its roster of malls in the eastern US and will work toward redeveloping the mall.[51]

There are five major shopping plazas in Charleston, two in the Kanawha City neighborhood—The Shops at Kanawha and Kanawha Landing—and three in the Southridge area, divided between Charleston and South Charleston—Southridge Centre, Dudley Farms Plaza, and The Shops at Trace Fork.

Parks and recreation

[edit]- University of Charleston Stadium at Laidley Field — Used for football, soccer, track, and festivals

- GoMart Ballpark — Stadium of the Charleston Dirty Birds

- Cato Park — Charleston's largest municipal park, including a golf course, Olympic-size swimming pool and picnic areas

- Coonskin Park — Includes swimming pool, boathouse, clubhouse with dining facilities, tennis courts, putt putt golf, an 18-hole par 3 golf course, driving range, and fishing lake. Schoenbaum Soccer Field and Amphitheatre inside the park is the home of West Virginia United soccer team

- Daniel Boone Park — A 4-acre (16,000 m2) park with a boat ramp, fishing and picnic facilities

- Danner Meadow Park

- Kanawha State Forest — A 9,300-acre (38 km2) forest, including 46 campsites (in the community of Loudendale)

- Magic Island — An area at the junction of the Elk River and the Kanawha River, near Kanawha Boulevard.

- Davis Park

- Haddad Riverfront Park

- Ruffner Park

- Joplin Park (South Charleston)

Sports

[edit]| Club | Sport | Founded | League | Venue |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charleston Dirty Birds | Baseball | 2005 | Atlantic League of Professional Baseball (Independent) | GoMart Ballpark |

| West Virginia United | Soccer | 2003 | USL League Two | Schoenbaum Stadium |

| West Virginia Wildfire | Women's American football | 2008 | Women's Spring Football League | TBA |

The West Virginia United is a soccer team that plays its home games at Schoenbaum Stadium in Charleston. The team plays in the USL League Two (USL2) — the fourth tier of the American Soccer Pyramid — in the South Atlantic Division of the Eastern Conference

Government

[edit]

Charleston functions has a mayor-council form of city government. The mayor is the city's designated chief executive, with the duty to see that all city laws and ordinances are enforced. The mayor gives general supervision over all executive departments, offices, and agencies of the city government and is the presiding officer of the council and a voting member thereof. Amy Goodwin was sworn in as mayor on January 7, 2019, and is Charleston's first female mayor.[52] Charleston also has a city manager, who is appointed by the mayor and approved by the council. Benjamin Mishoe took office as city manager in 2023. The city manager has supervision and control of the executive work and management of the heads of all departments under his or her control as directed by the mayor, makes all contracts for labor and supplies, and generally is responsible for all the city's business and administrative work.

The Charleston City Council has 26 members. Twenty of the members are elected from a specific ward within the city, and the other six are elected by the city at-large.

General elections for mayor, city council, and other city officers take place in November every four years, coinciding with midterm election races for Congress and the state legislature. Primary elections are held in May. The most recent election was in 2022. Until 2018, elections were held in off-cycle years, with primaries in March and general elections in May.[53]

- Jacob Goshorn, 1861 (elected but did not serve)[54][55]

- John A. Truslow, circa 1865[55]

- John Williams

- George Ritter, 1868–1869[55]

- John W. Wingfield, 1870[55]

- H. Clay Dickinson, 1871 (died in office)[55]

- John P. Hale, 1871[56]

- John Williams, 1872[55]

- C. P. Snyder, 1873[55]

- John D. White, 1874[55]

- John C. Ruby, 1875–1876[55][57]

- C. J. Botkin, 1877–1881[55]

- R. R. Delaney, 1881–1882[55]

- John D. Baines, 1883–1884[55]

- James Hall Huling, 1885–1886[55]

- Joseph L. Fry, 1887–1890[55]

- James B. Pemberton, 1891–1892[55][56]

- E. W. Staunton, 1893–1894[55]

- J. A. deGruyter, 1895–1898[55]

- W. Herman Smith, 1899–1900 (died in office)[55]

- John B. Floyd, 1900–1901

- George S. Morgan, 1901–[55]

- C. E. Rudesill

- John A. Jarrett

- James A. Holley

- William W. Wertz, 1929

- R. P. DeVan, 1934

- D. Boone Dawson, 1935–1947

- R. Carl Andrews, 1947–1950

- John T. Copenhaver, 1951–1959

- John A. Shanklin, 1959–1967

- Elmer H. Dodson, 1967–1971

- John G. Hutchinson, 1971–1980

- Joe F. Smith, 1980–1983

- James E. "Mike" Roark, 1983–1987

- Charles R. "Chuck" Gardner, 1987–1991

- Kent Strange Hall, 1991–1995

- G. Kemp Melton, 1995–1999

- Jay Goldman, 1999–2003[58]

- Danny Jones, 2003–2019[59]

- Amy Shuler Goodwin, 2019–present

Education

[edit]

Primary and secondary

[edit]Charleston has numerous schools that are part of Kanawha County Schools. The three high schools are:

- Capital High School, a public school in the community of Meadowbrook. It was established by the consolidation of Charleston High School and Stonewall Jackson High School. It opened in 1989.

- George Washington High School, a public school in the South Hills neighborhood. It opened in 1964.

- Charleston Catholic High School, a Catholic school at the eastern edge of the city's downtown. It opened in 1923.

Former high schools

[edit]- Charleston High School, across the street from CAMC General Hospital. It was founded in 1916 and closed in 1989.

- Stonewall Jackson High School, on the West Side. It was founded in 1940 and converted to a middle school in 1989 after Capital High School opened.

- Garnet High School was a historic African-American high school.

Colleges and universities

[edit]Charleston hosts a branch campus of West Virginia University that serves as a clinical campus for the university's medical and dental schools. Students at either school must complete their classwork at the main campus in Morgantown but can complete their clinical rotations at hospitals in Morgantown, the Eastern Panhandle, or Charleston. Students from West Virginia School of Osteopathic Medicine may also complete their clinical rotations at the branch campus after completing their first two academic years at the main campus in Lewisburg.

Charleston is also home to a 1,000-student private college, the University of Charleston, formerly Morris Harvey College. It is on MacCorkle Avenue, along the banks of the Kanawha River (directly across from the capitol), in South Ruffner.

In the immediate area are West Virginia State University in Institute and the South Charleston campus of both the BridgeValley Community and Technical College and Marshall University. The region is also home to the Charleston Branch of the Robert C. Byrd Institute for Advanced Flexible Manufacturing, an independent program administered by Marshall University providing access to computer numerical control (CNC) equipment for businesses.

BridgeValley Community and Technical College also has a campus in Montgomery.

Charleston was also home to West Virginia Junior College's Charleston campus until 2020, when it relocated to Cross Lanes.[60] WV Junior College is accredited by the Accrediting Council for Independent Colleges and Schools to award diplomas and associate degrees. Part of the Kanawha Valley for almost 115 years, WV Junior College was established as Capitol City Commercial College in 1892. It was originally established to train students in secretarial and business skills and has undergone changes in location and curriculum over the years.

Media

[edit]Charleston's only major newspaper is the Charleston Gazette-Mail. It was formerly two separate newspapers, the morning Charleston Gazette and afternoon Charleston Daily Mail. The city's first newspaper was the Farmers' Repository, first published in 1808.[16] Other newspapers included the 1819 Spectator and 1872 Kanawha Chronicle, a precursor to the modern Gazette-Mail.[15][16]

Radio

[edit]Charleston has 11 radio stations (AM and FM) licensed in the city. Most of them are owned either by the West Virginia Radio Corporation or by the Bristol Broadcasting Company.

| Call sign | Frequency | Format | Description / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| WCHS* | 580 AM | News / Talk[61] | 58 WCHS |

| WKAZ* | 680 AM | Oldies | The Oldies format was formerly on 107.3. |

| WBES* | 950 AM | Sportstalk | |

| WSWW* | 1490 AM | Sports | ESPN 1490 |

| WTSQ-LP | 88.1 FM | Freeform | |

| WVPB* | 88.5 FM | Public Radio[62] | NPR News, Classical Music, Mountain Stage, and other local and national programs. |

| WKVW | 93.3 FM | KLOVE Contemporary Christian | |

| WXAF* | 90.9 FM | Religious | |

| WZAC-FM | 92.5 FM | Classic Country | |

| WYNL | 94.5 FM | Contemporary Christian[63] | New Life Ninety Four Five |

| WKWS* | 96.1 FM | Classic Country | 96.1 KWS |

| WQBE-FM* | 97.5 FM | Country[64] | 97.5 WQBE. The Charleston MSA's #1 rated radio station, according to Arbitron. |

| WCST-FM | 98.7 FM | Classic Rock | 98.7 The Mountain |

| WVAF* | 99.9 FM | Adult Contemporary[65] | V-100 |

| WMXE | 100.9 FM | Classic Hits[66] | 100.9 The Mix |

| WVSR-FM* | 102.7 FM | Top 40[67] | Electric 102.7 |

| WKLC-FM | 105.1 FM | Rock[68] | Rock 105 |

| WRVZ | 107.3 FM | Hip Hop | 107.3 The Beat |

* represents radio stations that are licensed to the city of Charleston.

Television

[edit]The Charleston–Huntington TV market is the second-largest television market by area east of the Mississippi River and 64th-largest in terms of households in the U.S., serving counties in central West Virginia, eastern Kentucky, and southern Ohio. There are four VHF and ten UHF television stations in the market. WSAZ-TV was the market's first station, going on air in 1949.[69]

| Call sign | Channel | Description |

|---|---|---|

| WSAZ-TV | 3 | (NBC) / (MyNetworkTV on DT2) |

| WCHS-TV | 8 | (ABC) / (Fox on DT2) |

| WVAH | 11 | (Catchy Comedy) |

| WOWK | 13 | (CBS) |

| WLPX | 29 | (ION) |

| WQCW | 30 | (The CW) |

| WVPB | 33 | (PBS) |

| WTSF | 61 | Ashland, Kentucky (Daystar) |

Transportation

[edit]Air

[edit]

Yeager Airport is West Virginia's largest airport, serving more than twice as many passengers as all other airports in the state combined. It is two miles (three kilometers) north of Interstate 64 and Interstate 77, accessible via WV 114. It is also home to the McLaughlin Air National Guard Base.

Rail

[edit]

Amtrak, the national passenger rail service, provides tri-weekly service to Charleston via the Cardinal routes. The Amtrak station is on the south side of the Kanawha River, at 350 MacCorkle Avenue, near downtown.

Until the 1960s, several daily Chesapeake and Ohio Railway trains traversed central West Virginia, making stops in Charleston. Destinations in the midwest included St. Louis, Chicago, Detroit and Louisville. To the east the trains terminated in either Washington, D.C. or Newport News, Virginia. These featured the Fast Flying Virginian, George Washington, and the Sportsman. Into the late 1940s, the New York Central Railroad operated passenger trains between Columbus, Ohio, and Charleston.[70]

River

[edit]

Interstate 64 crosses the Kanawha River four times as it passes through the Charleston metropolitan area. The Elk River flows into the Kanawha River in downtown Charleston.

Roads

[edit]

Charleston is served by Interstate 64, Interstate 77, and Interstate 79. The West Virginia Turnpike's northern terminus is at the city's southeastern end. Two U.S. routes, US 60 and US 119, cut through the city center. US 21 and US 35 formerly ran through Charleston.

WV 25, WV 61, WV 62, and WV 114 are all state highways that are within Charleston's city limits.

Mass transit

[edit]Charleston is served by Kanawha Valley Regional Transportation Authority.

Infrastructure

[edit]Utilities

[edit]Electricity in Charleston is provided by Appalachian Power, a division of American Electric Power of Columbus, Ohio. Appalachian Power is headquartered in Charleston. Suddenlink Communications provides the Charleston area's Cable TV. Landline phone service in Charleston is provided by Frontier Communications. The city's water supply is provided by Charleston-based West Virginia American Water, a subsidiary of American Water[71] of Voorhees Township, New Jersey. Charleston's water supply is pumped from the Elk River and treated at the Kanawha Valley Water Treatment Plant. Its natural gas is supplied by Mountaineer Gas, a division of Allegheny Energy of Greensburg, Pennsylvania.

Law enforcement

[edit]The Charleston Police Department (CPD) is West Virginia's second-largest police department[72] and the state's largest municipal/city police department. In 2008, Charleston Police had 168 sworn officers, two animal control officers, and 29 civilian employees.[72]

Healthcare

[edit]CAMC (Charleston Area Medical Center) a complex of hospitals throughout the city.

Thomas Health is a complex of hospitals and healthcare centers in the Charleston area.[73]

Highland Hospital (Kanawha City) is a behavioral health facility.

Popular culture

[edit]- Charleston is a location in the game The Sum of All Fears, based on Tom Clancy's book of the same name[74]

- Charleston is a location in the game Fallout 76[75]

Notable people

[edit]- Diplomat and attorney Harriet C. Babbitt, born in Charleston

- Olympic shot put gold and silver medalist Randy Barnes

- MMA fighter Brian Bowles, bantamweight champion

- Extreme metal band Byzantine formed and based in Charleston

- Kevin Canady, Professional wrestler founder of IWA East Coast

- Jean Carson, Actress

- Cisco Systems CEO John Chambers

- H. Rodgin Cohen, banker

- William E. Chilton, Newspaper publisher and U.S. Senator

- Basudeb DasSarma, Chemist

- Douglas Dick, Actor

- Barbara DuMetz, Photographer was born in Charleston

- George Crumb, Classical composer

- Dorian Etheridge, linebacker for the Atlanta Falcons

- Sarah Feinberg, interim president of the New York City Transit Authority and former head of the Federal Railroad Administration

- Conchata Ferrell, Actress

- Sierra Ferrell, Musician, Singer-Songwriter

- Paul Frame, chiropractor and former ballet dancer

- Peter Frame, ballet dancer

- William Frischkorn, cyclist

- Actress and Alias star Jennifer Garner was born in Houston, moved with her family to Princeton, West Virginia, then Charleston as a child and grew up there, graduating from city's George Washington High School

- Elizabeth Harden Gilmore, civil rights activist

- George H. Goodrich, justice, Superior Court of the District of Columbia

- Alexis Hornbuckle, professional basketball player, NCAA champion at Tennessee

- Professional baseball player and coach J. R. House

- Basketball player and broadcaster Hot Rod Hundley

- John G. Hutchinson, mayor 1971–80

- Soap opera actress Lesli Kay who has appeared on As the World Turns, General Hospital and The Bold and the Beautiful

- George King, NBA player and head coach of West Virginia and Purdue

- Former Major League Baseball player and current sportscaster John Kruk was born in Charleston, but grew up in Keyser

- Special effects artist Robert "RJ" Haddy was born and resides in Charleston

- Actress Allison Hayes

- Actress Ann Magnuson

- NASA astronaut Jon McBride was born in Charleston[76]

- Actor Tom McBride Actor from Friday the 13th Part II

- George Armitage Miller, one of the founders of the field of cognitive psychology, was born here.

- Would-be presidential assassin Sara Jane Moore was born in Charleston

- Actor Nick Nolte lived in the South Hills neighborhood of Charleston during the 1980s

- National Football League player Rick Nuzum was born in Charleston

- Pop singer Caroline Peyton

- Phil Pfister, world's strongest man (2006), is a firefighter for CFD

- American author Eugenia Price

- Creator of Droodles and television personality Roger Price

- Author and technology policy analyst Alec Ross[77]

- Actress Kristen Ruhlin

- Country singer Red Sovine was born in Charleston

- Civil rights activist Rev. Leon Sullivan was born in Charleston

- NFL player Russ Thomas, general manager of Detroit Lions 1967–89, attended high school in Charleston

- Actor and True Blood star Sam Trammell was born in New Orleans, but grew up in Charleston, graduating from city's George Washington High School

- Tennis player Anne White attended John Adams Junior High School and graduated from George Washington High School.[78]

- Miami Heat point guard Jason Williams, who grew up in Belle in the same vicinity, was a high school teammate of Moss

- Daniel Webster, longest-serving Florida legislator, was born in Charleston[79]

- Athlete and coach Harry Young, member of College Football Hall of Fame

- Former NFL player Dennis Harrah

Sister city

[edit]Charleston's sister city is:[80]

Banská Bystrica, Slovakia (2009)[81]

Banská Bystrica, Slovakia (2009)[81]

See also

[edit]- USAT General Frank M. Coxe was built in Charleston in 1922 by the Charles Ward Engineering Works. She served as an Army transport and later a cruise ship on San Francisco Bay. She is now preserved as a floating restaurant in Burlingame, California, just south of San Francisco.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the expected highest and lowest temperature readings at any point during the year or given month) calculated based on data at said location from 1981 to 2020.

References

[edit]- ^ "I'm Charlie West". Charleston Convention & Visitors Bureau. Archived from the original on June 20, 2015. Retrieved June 5, 2015.

- ^ "City Council". City of Charleston, West Virginia. Retrieved October 13, 2024.

- ^ a b "2024 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 13, 2024.

- ^ a b c U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Charleston, West Virginia

- ^ a b c "Explore Census Data". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 13, 2024.

- ^ a b c "City and Town Population Totals: 2020-2023". United States Census Bureau. October 13, 2024. Retrieved October 13, 2024.

- ^ "Look Up a ZIP Code™". USPS. October 13, 2024.

- ^ "Charleston (WV) sales tax rate". Retrieved October 13, 2024.

- ^ "Nielsen US Media Market rankings" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on March 18, 2015.

- ^ Morris, William (March 19, 1922). "William Morris History of First Settler to Locate in Valley of Kanawha WV 1773". Charleston Daily Mail. No. Morning Issue. newspapers.com. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ Shepherd, Samuel (1835). Statutes at Large of Virginia from October Session 1792 to December Session 1806 (1st ed.). Richmond, Virginia: Commonwealth of Virginia. p. 322. ISBN 0404060102.

- ^ "First Natural Gas Well – West Virginia (WV) Cyclopedia". Wvexp.com. December 10, 2005. Archived from the original on March 15, 2013. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ a b c Richard A. Andre. "Charleston". West Virginia Encyclopedia. Charleston, WV: West Virginia Humanities Council. Archived from the original on March 5, 2017. Retrieved March 7, 2017. (Includes timeline)

- ^ Kanawha County was named in honor of the Great Kanawha River that runs through the county. The river was named for the Indian tribe that once lived in the area. The spelling of the Indian tribe varied at the time from Conoys to Conois to Kanawha. The latter spelling was used and has gained acceptance over time. "Kanawha County History". Archived from the original on June 16, 2010. Retrieved October 31, 2009. (December 29, 2008)

- ^ a b c d e f g h Federal Writers' Project 1941.

- ^ a b c "U.S. Newspaper Directory". Chronicling America. Washington DC: Library of Congress. Archived from the original on March 7, 2017. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- ^ Easter, Makeda (April 4, 2020). "Slavery Documents from Southern Saltmakers Bring Light to Dark History". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 2, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Hellmann 2006.

- ^ Davies Project. "American Libraries before 1876". Princeton University. Archived from the original on March 2, 2015. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- ^ Britannica 1910.

- ^ a b "West Virginia State Archives". West Virginia Division of Culture and History. Archived from the original on March 16, 2017. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- ^ Appleton Prentiss Clark Griffin (1907), Bibliography of American Historical Societies, Annual Report of the American Historical Association (2nd ed.), Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, pp. 942+, hdl:2027/uc2.ark:/13960/t7dr2pp5f,

West Virginia

- ^ a b Chamber of Commerce 1901, p. [page needed].

- ^ a b "About Us: History". Charleston: Kanawha County Public Library. Archived from the original on March 7, 2017. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- ^ "West Virginia Encyclopedia". Charleston, WV: West Virginia Humanities Council. Archived from the original on March 19, 2017. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ a b "Our History". University of Charleston. Archived from the original on March 8, 2017. Retrieved March 8, 2017. (Timeline)

- ^ Nelson, Clarence M. (December 28, 2005). "Institute and WWII: Creation of Synthetic Rubber Plant Was Exciting". redOrbit. Archived from the original on September 20, 2009. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ^ "Home". www.mountainstage.org. Archived from the original on October 30, 2009. Retrieved October 26, 2019.

- ^ "City of Charleston, West Virginia". Archived from the original on December 5, 1998 – via Internet Archive, Wayback Machine.

- ^ Kevin Hyde; Tamie Hyde (eds.). "United States of America: West Virginia". Official City Sites. Utah. OCLC 40169021. Archived from the original on September 25, 2000.

- ^ Lilly, John (January 21, 2016). "West Virginia Music Hall of Fame". West Virginia Encyclopedia. West Virginia Humanities Council. Archived from the original on November 8, 2021. Retrieved November 29, 2021.

- ^ "Level III Ecoregions of West Virginia". U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Archived from the original on June 28, 2014. Retrieved September 29, 2013.

- ^ "Charleston-Huntington Climate Summary – Eyewitness News Storm Team Weather". Wchstv.com. Archived from the original on March 4, 2013. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on May 1, 2021. Retrieved June 13, 2021.

- ^ "Station: Charleston Yeager AP, WV". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 13, 2021.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "P004: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – Charleston city, West Virginia". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 13, 2024.

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Charleston city, West Virginia". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 13, 2024.

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Charleston city, West Virginia". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 13, 2024.

- ^ "US Census Bureau, Table P16: Household Type". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 13, 2024.

- ^ "How many people live in Charleston city, West Virginia". USA Today. Retrieved October 13, 2024.

- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Charleston city, West Virginia". www.census.gov. Retrieved October 13, 2024.

- ^ "Home - Charleston Area Alliance, WV". charlestonareaalliance.org. Archived from the original on May 31, 2013. Retrieved October 26, 2019.

- ^ "AEP.com". aep.com. Archived from the original on March 4, 2007. Retrieved October 26, 2019.

- ^ "Symphony Sunday". West Virginia Symphony League. Archived from the original on June 8, 2009.

- ^ "Our Mission". West Virginia Film Festival. Archived from the original on April 29, 2009.

- ^ "Vandalia Gathering". www.wvculture.org. Archived from the original on September 17, 2019. Retrieved October 26, 2019.

- ^ "Home | FestivAll". festivallcharleston.com. Archived from the original on September 30, 2019. Retrieved October 26, 2019.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ Conn, Anthony (February 22, 2021). "What is next for the Charleston Town Center Mall?". WCHS TV. Archived from the original on September 24, 2021. Retrieved September 24, 2021.

- ^ BSHARAH, MEGAN (May 10, 2021). "Mayor: Charleston Town Center sale is 'a step forward in the right direction'". WCHS. Archived from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved June 24, 2021.

- ^ Shinkle, Leanne. "Amy Goodwin sworn in as first female mayor in Charleston". WSAZ. Archived from the original on November 7, 2018. Retrieved January 15, 2019.

- ^ Fallon, Paul (February 5, 2013). "New measure would shorten Charleston council members' terms". Charleston Gazette-Mail. Retrieved May 7, 2023.

- ^ W. S. Laidley (1911), History of Charleston and Kanawha County, West Virginia, and Representative Citizens, Chicago: Richmond-Arnold Publishing Co., pp. 166–169, OCLC 3645365, archived from the original on March 7, 2017, retrieved August 25, 2017 – via Internet Archive,

List of mayors

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Chamber of Commerce 1901, p. 31.

- ^ a b "West Virginia Encyclopedia". Charleston, WV: West Virginia Humanities Council. Archived from the original on March 19, 2017. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- ^ Thomas Condit Miller; Hu Maxwell (1913). West Virginia and Its People. Vol. 3. New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Company. Archived from the original on July 1, 2014.

- ^ "Mayor's Office". Cityofcharleston.org. Archived from the original on December 16, 2000 – via Internet Archive, Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Office of the Mayor". Cityofcharleston.org. Archived from the original on August 10, 2003.

- ^ writer, Ryan Quinn Staff (August 2, 2020). "WV Junior College leaving longtime Charleston location for Cross Lanes". Charleston Gazette-Mail. Archived from the original on April 16, 2021. Retrieved April 16, 2021.

- ^ "58WCHS.COM". www.58wchs.com. Archived from the original on January 7, 2007. Retrieved October 26, 2019.

- ^ "West Virginia Public Broadcasting". www.wvpublic.org. Archived from the original on June 5, 2009. Retrieved October 26, 2019.

- ^ "Charleston's Supertalk 950 WVTS – Home". Wvtsam950.com. January 11, 2008. Archived from the original on December 13, 2012. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ "97.5 WQBE | Twenty-Four Carrot Country". 97.5 WQBE. Archived from the original on January 8, 2007. Retrieved October 26, 2019.

- ^ "V100 | Better Music For A Better Workday | Charleston, WV". V100 | Better Music For A Better Workday | Charleston, WV. Archived from the original on October 26, 2019. Retrieved October 26, 2019.

- ^ Homepage – Classic Hits 100.9 The Mix Archived December 5, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Electric 102.7". Electric 102.7. Archived from the original on October 26, 2019. Retrieved October 26, 2019.

- ^ Homepage – ROCK 105 Archived February 6, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Charles A. Alicoate, ed. (1960), "Television Stations: West Virginia", Radio Annual and Television Year Book, New York: Radio Daily Corp., OCLC 10512206

- ^ "Table 35" (PDF), New York Central RR Timetable, April 1948, archived from the original (PDF) on September 11, 2018

- ^ "American Water". February 27, 2007. Archived from the original on February 27, 2007. Retrieved October 26, 2019.

- ^ a b Department's Official web site

- ^ "About Us". Thomas Health. May 5, 2020. Archived from the original on March 2, 2021. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

- ^ Gorski, Sam (June 16, 2023). "5 video games set in West Virginia". WBOY. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ Forward, Jordan (October 8, 2018). "Fallout 76 locations - all the map markers confirmed across post-apocalyptic West Virginia". PC GamesN. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ "Astronaut Biography: Jon McBride". Spacefacts.de. Archived from the original on October 10, 2012. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ Wood, Pamela (May 24, 2018). "Democrat Alec Ross, tech expert and author, says as Maryland governor he'll focus on 'what's next'". baltimoresun.com. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- ^ Simms, J.T. (July 6, 1999). "Women have long sports history". Daily Mail. Archived from the original on June 15, 2008. Retrieved April 24, 2008.

- ^ Hollis, Mark (August 14, 1996). "Webster is Poised to Become House Speaker". The Ledger. Lakeland, Florida. The New York Times Company. p. D4. Archived from the original on August 18, 2014. Retrieved September 1, 2010.

- ^ [1] Archived September 26, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Banská Bystrica EN Sister cities". March 3, 2012. Archived from the original on March 3, 2012. Retrieved August 5, 2019.

Bibliography

[edit]- J. A. Gibbons (1872). Kanawha Valley: Its Resources and Developments; Also, Special Business Directory of Charleston and Other Cities. Charleston: Gibbens, Atkinson & Co., Printers. Archived from the original on March 8, 2017. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- D.H. Strother (1872). Capital of West Virginia and the Great Kanawha Valley. Charleston: Journal Office. Archived from the original on March 8, 2017. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- J.H. Chataigne, ed. (1882). "Charleston". Chesapeake & Ohio Railway Directory. Richmond, VA. pp. 349–356. OCLC 23244118. Archived from the original on March 8, 2017. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Charleston". West Virginia State Gazetteer and Business Directory. Detroit: R.L. Polk & Co. 1882.

- History of Kanawha County, and Biographical Sketches of Prominent Men. Charleston: Miller & Graham. 1885. Archived from the original on August 26, 2017. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- Charleston Chamber of Commerce (1901). Century Chronicle, Devoted to the Capital City. The Chamber. hdl:2027/hvd.hx4tu5.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 945.

- W. S. Laidley (1911), History of Charleston and Kanawha County, West Virginia, and Representative Citizens, Chicago: Richmond-Arnold Publishing Co., OCLC 3645365, OL 25173948M

- Thomas Condit Miller; Hu Maxwell (1913). "Kanawha County". West Virginia and Its People. New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Company. Archived from the original on March 7, 2017. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- Code of Ordinances of the City of Charleston, West Virginia. Laws, etc. (Code of ordinances : 1921 ed.). Tribune Print. Co. 1921. Archived from the original on August 25, 2017. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- Federal Writers' Project (1941). "Charleston". West Virginia: A Guide to the Mountain State. American Guide Series. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 177+. ISBN 9781603540476. Archived from the original on October 11, 2013. Retrieved August 25, 2017 – via Google Books. + chronology

- Jean Callahan (August 1978). "Cancer Valley". Mother Jones. San Francisco. Archived from the original on March 8, 2017. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- George Thomas Kurian (1994), "Charleston, West Virginia", World Encyclopedia of Cities, Vol. 1: North America, Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO, OL 1431653M, archived from the original on October 27, 2021, retrieved December 26, 2019 – via Internet Archive (fulltext)

- Stan Bumgardner (2006). Charleston. Postcard History Series. Charleston, SC: Arcadia. ISBN 978-0-7385-4265-2. Archived from the original on March 8, 2017. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- Paul T. Hellmann (2006). "West Virginia: Charleston". Historical Gazetteer of the United States. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 1-135-94859-3. Archived from the original on August 18, 2018. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Charleston, West Virginia at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Charleston, West Virginia at Wikimedia Commons

- City of Charleston, WV – official website

- Items related to Charleston, various dates (via Digital Public Library of America).

- "Charleston, a city, the capital of West Virginia". The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

- "Charleston. The capital of West Virginia". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- "Charleston, the capital of West Virginia". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- "Charleston, capital of West Virginia". The New Student's Reference Work. 1914.

- "Charleston, a city, capital of the State of West Virginia". Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

- FestivALL Charleston

- Charleston, West Virginia

- Charleston, West Virginia metropolitan area

- Cities in West Virginia

- County seats in West Virginia

- Populated places established in 1788

- Cities in Kanawha County, West Virginia

- Populated places on the Kanawha River

- 1788 establishments in Virginia

- State capitals in the United States

- Populated places on the Elk River (West Virginia)