Thomas Aquinas

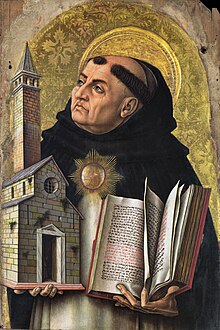

Thomas Aquinas OP (/əˈkwaɪnəs/ ə-KWY-nəs; Italian: Tommaso d'Aquino, lit. 'Thomas of Aquino'; c. 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian[6] Dominican friar and priest, the foremost Scholastic thinker,[7] as well one of the most influential philosophers and theologians in the Western tradition.[8] He was from the county of Aquino in the Kingdom of Sicily.

Thomas was a proponent of natural theology and the father of a school of thought (encompassing both theology and philosophy) known as Thomism. Central to his thought was the doctrine of natural law, which he argued was accessible to human reason and grounded in the very nature of human beings, providing a basis for understanding individual rights and moral duties.[9] He argued that God is the source of the light of natural reason and the light of faith.[10] He embraced[11] several ideas put forward by Aristotle and attempted to synthesize Aristotelian philosophy with the principles of Christianity.[12] Aquinas' natural law theory has been influential in shaping ideas about human liberty and the moral limits of government authority.[13][14] He has been described as "the most influential thinker of the medieval period"[15] and "the greatest of the medieval philosopher-theologians".[16]

Thomas's best-known works are the unfinished Summa Theologica, or Summa Theologiae (1265–1274), the Disputed Questions on Truth (1256–1259) and the Summa contra Gentiles (1259–1265). His commentaries on Christian Scripture and on Aristotle also form an important part of his body of work. He is also notable for his Eucharistic hymns, which form a part of the Church's liturgy.[17]

As a Doctor of the Church, Thomas Aquinas is considered one of the Catholic Church's greatest theologians and philosophers.[18] He is known in Catholic theology as the Doctor Angelicus ("Angelic Doctor", with the title "doctor" meaning "teacher"), and the Doctor Communis ("Universal Doctor").[a] In 1999, John Paul II added a new title to these traditional ones: Doctor Humanitatis ("Doctor of Humanity/Humaneness").[19]

Biography

[edit]Early life (1225–1244)

[edit]Thomas Aquinas was most likely born in the family castle of Roccasecca,[20] near Aquino, controlled at that time by the Kingdom of Sicily (in present-day Lazio, Italy), c. 1225.[21] He was born to the most powerful branch of the family, and his father, Landulf of Aquino, was a man of means. As a knight in the service of Emperor Frederick II, Landulf of Aquino held the title miles.[22] Thomas's mother, Theodora, belonged to the Rossi branch of the Neapolitan Caracciolo family.[23] Landulf's brother Sinibald was abbot of Monte Cassino, the oldest Benedictine monastery. While the rest of the family's sons pursued military careers,[24] the family intended for Thomas to follow his uncle into the abbacy;[25] this would have been a normal career path for a younger son of Southern Italian nobility.[26]

At the age of five Thomas began his early education at Monte Cassino, but after the military conflict between Emperor Frederick II and Pope Gregory IX spilt into the abbey in early 1239, Landulf and Theodora had Thomas enrolled at the studium generale (university) established by Frederick in Naples.[27] There, his teacher in arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music was Petrus de Ibernia.[28] It was at this university that Thomas was presumably introduced to Aristotle, Averroes and Maimonides, all of whom would influence his theological philosophy.[29] During his study at Naples, Thomas also came under the influence of John of St. Julian, a Dominican preacher in Naples, who was part of the active effort by the Dominican Order to recruit devout followers.[30]

At the age of nineteen, Thomas resolved to join the Dominican Order. His change of heart, however, did not please his family.[31] In an attempt to prevent Theodora's interference in Thomas's choice, the Dominicans arranged to move Thomas to Rome, and from Rome, to Paris.[32] However, while on his journey to Rome, per Theodora's instructions, his brothers seized him as he was drinking from a spring and took him back to his parents at the castle of Monte San Giovanni Campano.[32]

Thomas was held prisoner for almost one year in the family castles at Monte San Giovanni and Roccasecca in an attempt to prevent him from assuming the Dominican habit and to push him into renouncing his new aspiration.[29] Political concerns prevented the Pope from ordering Thomas's release, which had the effect of extending Thomas's detention.[33] Thomas passed this time of trial tutoring his sisters and communicating with members of the Dominican Order.[29]

Family members became desperate to dissuade Thomas, who remained determined to join the Dominicans. At one point, two of his brothers resorted to the measure of hiring a prostitute to seduce him, presumably because sexual temptation might dissuade him from a life of celibacy. According to the official records for his canonization, Thomas drove her away wielding a burning log—with which he inscribed a cross onto the wall—and fell into a mystical ecstasy; two angels appeared to him as he slept and said, "Behold, we gird thee by the command of God with the girdle of chastity, which henceforth will never be imperilled. What human strength can not obtain, is now bestowed upon thee as a celestial gift." From then onwards, Thomas was given the grace of perfect chastity by Christ, a girdle he wore till the end of his life. The girdle was given to the ancient monastery of Vercelli in Piedmont, and is now at Chieri, near Turin.[34][35]

By 1244, seeing that all her attempts to dissuade Thomas had failed, Theodora sought to save the family's dignity, arranging for Thomas to escape at night through his window. In her mind, a secret escape from detention was less damaging than an open surrender to the Dominicans. Thomas was sent first to Naples and then to Rome to meet Johannes von Wildeshausen, the Master General of the Dominican Order.[36]

Paris, Cologne, Albert Magnus, and first Paris regency (1245–1259)

[edit]

In 1245, Thomas was sent to study at the Faculty of the Arts at the University of Paris, where he most likely met Dominican scholar Albertus Magnus,[37] then the holder of the Chair of Theology at the College of St. James in Paris.[38] When Albertus was sent by his superiors to teach at the new studium generale at Cologne, in 1248,[37] Thomas followed him, declining Pope Innocent IV's offer to appoint him abbot of Monte Cassino as a Dominican.[25] Albertus then appointed the reluctant Thomas magister studentium.[26] Because Thomas was quiet and did not speak much, some of his fellow students thought he was slow. But Albertus prophetically exclaimed: "You call him the dumb ox [bos mutus], but in his teaching he will one day produce such a bellowing that it will be heard throughout the world".[25]

Thomas taught in Cologne as an apprentice professor (baccalaureus biblicus), instructing students on the books of the Old Testament and writing Expositio super Isaiam ad litteram (Literal Commentary on Isaiah), Postilla super Ieremiam (Commentary on Jeremiah), and Postilla super Threnos (Commentary on Lamentations).[39] In 1252, he returned to Paris to study for a master's degree in theology. He lectured on the Bible as an apprentice professor, and upon becoming a baccalaureus Sententiarum (bachelor of the Sentences)[40] he devoted his final three years of study to commenting on Peter Lombard's Sentences. In the first of his four theological syntheses, Thomas composed a massive commentary on the Sentences entitled, Scriptum super libros Sententiarium (Commentary on the Sentences). Aside from his master's writings, he wrote De ente et essentia (On Being and Essence) for his fellow Dominicans in Paris.[25]

In the spring of 1256, Thomas was appointed regent master in theology at Paris and one of his first works upon assuming this office was Contra impugnantes Dei cultum et religionem (Against Those Who Assail the Worship of God and Religion), defending the mendicant orders, which had come under attack by William of Saint-Amour.[41] During his tenure from 1256 to 1259, Thomas wrote numerous works, including: Quaestiones Disputatae de Veritate (Disputed Questions on Truth), a collection of twenty-nine disputed questions on aspects of faith and the human condition[42] prepared for the public university debates he presided over during Lent and Advent;[43] Quaestiones quodlibetales (Quodlibetal Questions), a collection of his responses to questions de quodlibet posed to him by the academic audience;[42] and both Expositio super librum Boethii De trinitate (Commentary on Boethius's De trinitate) and Expositio super librum Boethii De hebdomadibus (Commentary on Boethius's De hebdomadibus), commentaries on the works of 6th-century Roman philosopher Boethius.[44] By the end of his regency, Thomas was working on one of his most famous works, Summa contra Gentiles.[45]

Naples, Orvieto, Rome (1259–1268)

[edit]In 1259, Thomas completed his first regency at the studium generale and left Paris so that others in his order could gain this teaching experience. He returned to Naples where he was appointed as general preacher by the provincial chapter of 29 September 1260. In September 1261 he was called to Orvieto as conventual lector, where he was responsible for the pastoral formation of the friars unable to attend a studium generale. In Orvieto, Thomas completed his Summa contra Gentiles, wrote the Catena aurea (The Golden Chain),[46] and produced works for Pope Urban IV such as the liturgy for the newly created feast of Corpus Christi and the Contra errores graecorum (Against the Errors of the Greeks).[45] Some of the hymns that Thomas wrote for the feast of Corpus Christi are still sung today, such as the Pange lingua (whose final two verses are the famous Tantum ergo), and Panis angelicus. Modern scholarship has confirmed that Thomas was indeed the author of these texts, a point that some had contested.[47]

In February 1265, the newly elected Pope Clement IV summoned Thomas to Rome to serve as papal theologian. This same year, he was ordered by the Dominican Chapter of Agnani[48] to teach at the studium conventuale at the Roman convent of Santa Sabina, founded in 1222.[49] The studium at Santa Sabina now became an experiment for the Dominicans, the Order's first studium provinciale, an intermediate school between the studium conventuale and the studium generale. Prior to this time, the Roman Province had offered no specialized education of any sort, no arts, no philosophy; only simple convent schools, with their basic courses in theology for resident friars, were functioning in Tuscany and the meridionale during the first several decades of the order's life. The new studium provinciale at Santa Sabina was to be a more advanced school for the province.[50] Tolomeo da Lucca, an associate and early biographer of Thomas, tells us that at the Santa Sabina studium Thomas taught the full range of philosophical subjects, both moral and natural.[51]

While at the Santa Sabina studium provinciale, Thomas began his most famous work, the Summa Theologiae,[46] which he conceived specifically suited to beginner students: "Because a doctor of Catholic truth ought not only to teach the proficient, but to him pertains also to instruct beginners. As the Apostle says in 1 Corinthians 3:1–2, as to infants in Christ, I gave you milk to drink, not meat, our proposed intention in this work is to convey those things that pertain to the Christian religion in a way that is fitting to the instruction of beginners."[52] While there he also wrote a variety of other works like his unfinished Compendium Theologiae and Responsio ad fr. Ioannem Vercellensem de articulis 108 sumptis ex opere Petri de Tarentasia (Reply to Brother John of Vercelli Regarding 108 Articles Drawn from the Work of Peter of Tarentaise).[44]

In his position as head of the studium, Thomas conducted a series of important disputations on the power of God, which he compiled into his De potentia.[53] Nicholas Brunacci [1240–1322] was among Thomas's students at the Santa Sabina studium provinciale and later at the Paris studium generale. In November 1268, he was with Thomas and his associate and secretary Reginald of Piperno as they left Viterbo on their way to Paris to begin the academic year.[54] Another student of Thomas's at the Santa Sabina studium provinciale was Blessed Tommasello da Perugia.[55]

Thomas remained at the studium at Santa Sabina from 1265 until he was called back to Paris in 1268 for a second teaching regency.[53] With his departure for Paris in 1268 and the passage of time, the pedagogical activities of the studium provinciale at Santa Sabina were divided between two campuses. A new convent of the Order at the Church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva began in 1255 as a community for women converts but grew rapidly in size and importance after being given over to the Dominicans friars in 1275.[49] In 1288, the theology component of the provincial curriculum for the education of the friars was relocated from the Santa Sabina studium provinciale to the studium conventuale at Santa Maria sopra Minerva, which was redesignated as a studium particularis theologiae.[56] This studium was transformed in the 16th century into the College of Saint Thomas (Latin: Collegium Divi Thomæ). In the 20th century, the college was relocated to the convent of Saints Dominic and Sixtus and was transformed into the Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas, (aka the Angelicum).

Quarrelsome second Paris regency (1269–1272)

[edit]

In 1268, the Dominican Order assigned Thomas to be regent master at the University of Paris for a second time, a position he held until the spring of 1272. Part of the reason for this sudden reassignment appears to have arisen from the rise of "Averroism" or "radical Aristotelianism" in the universities. In response to these perceived errors, Thomas wrote two works, one of them being De unitate intellectus, contra Averroistas (On the Unity of Intellect, against the Averroists) in which he reprimands Averroism as incompatible with Christian doctrine.[57] During his second regency, he finished the second part of the Summa and wrote De virtutibus and De aeternitate mundi, contra murmurantes (On the Eternity of the World, against Grumblers),[53] the latter of which dealt with controversial Averroist and Aristotelian beginninglessness of the world.[58]

Disputes with some important Franciscans conspired to make his second regency much more difficult and troubled than the first. A year before Thomas re-assumed the regency at the 1266–67 Paris disputations, Franciscan master William of Baglione accused Thomas of encouraging Averroists, most likely counting him as one of the "blind leaders of the blind". Eleonore Stump says, "It has also been persuasively argued that Thomas Aquinas's De aeternitate mundi was directed in particular against his Franciscan colleague in theology, John Pecham."[58]

Thomas was deeply disturbed by the spread of Averroism and was angered when he discovered Siger of Brabant teaching Averroistic interpretations of Aristotle to Parisian students.[59] On 10 December 1270, the Bishop of Paris, Étienne Tempier, issued an edict condemning thirteen Aristotelian and Averroistic propositions as heretical and excommunicating anyone who continued to support them.[60] Many in the ecclesiastical community, the so-called Augustinians, were fearful that this introduction of Aristotelianism and the more extreme Averroism might somehow contaminate the purity of the Christian faith. In what appears to be an attempt to counteract the growing fear of Aristotelian thought, Thomas conducted a series of disputations between 1270 and 1272: De virtutibus in communi (On Virtues in General), De virtutibus cardinalibus (On Cardinal Virtues), and De spe (On Hope).[61]

Late career and cessation of writing (1272–1274)

[edit]

In 1272, Thomas took leave from the University of Paris when the Dominicans from his home province called upon him to establish a studium generale wherever he liked and staff it as he pleased. He chose to establish the institution in Naples and moved there to take his post as regent master.[53] He took his time at Naples to work on the third part of the Summa while giving lectures on various religious topics. He also preached to the people of Naples every day in Lent of 1273. These sermons on the Commandments, the Creed, the Our Father, and Hail Mary were very popular.[62]

Thomas has been traditionally ascribed with the ability to levitate and as having had various mystical experiences. For example, G. K. Chesterton wrote that "His experiences included well-attested cases of levitation in ecstasy; and the Blessed Virgin appeared to him, comforting him with the welcome news that he would never be a Bishop."[63] It is traditionally held that on one occasion, in 1273, at the Dominican convent of Naples in the chapel of Saint Nicholas,[64] after Matins, Thomas lingered and was seen by the sacristan Domenic of Caserta to be levitating in prayer with tears before an icon of the crucified Christ. Christ said to Thomas, "You have written well of me, Thomas. What reward would you have for your labor?" Thomas responded, "Nothing but you, Lord."[65]

On 6 December 1273, another mystical experience took place. While Thomas was celebrating Mass, he experienced an unusually long ecstasy.[66] Because of what he saw, he abandoned his routine and refused to dictate to his socius Reginald of Piperno. When Reginald begged him to get back to work, Thomas replied: "Reginald, I cannot, because all that I have written seems like straw to me"[67] (mihi videtur ut palea).[68] As a result, the Summa Theologica would remain uncompleted.[69] What exactly triggered Thomas's change in behaviour is believed by some to have been some kind of supernatural experience of God.[70] After taking to his bed, however, he did recover some strength.[71]

In 1274, Pope Gregory X summoned Thomas to attend the Second Council of Lyon. The council was to open 1 May 1274, and it was Gregory's attempt to try to heal the Great Schism of 1054, which had divided the Catholic Church in the West from the Eastern Orthodox Church.[72] At the meeting, Thomas's work for Pope Urban IV concerning the Greeks, Contra errores graecorum, was to be presented.[73] However, on his way to the council, riding on a donkey along the Appian Way,[72] he struck his head on the branch of a fallen tree and became seriously ill again. He was then quickly escorted to Monte Cassino to convalesce.[71] After resting for a while, he set out again but stopped at the Cistercian Fossanova Abbey after again falling ill.[74] The monks nursed him for several days,[75] and as he received his last rites he prayed: "I have written and taught much about this very holy Body, and about the other sacraments in the faith of Christ, and about the Holy Roman Church, to whose correction I expose and submit everything I have written."[76] He died on 7 March 1274[74] while giving commentary on the Song of Songs.[77]

Legacy, veneration, and modern reception

[edit]Condemnation of 1277

[edit]In 1277, Étienne Tempier, the same bishop of Paris who had issued the condemnation of 1270, issued another, more extensive, condemnation. One aim of this condemnation was to clarify that God's absolute power transcended any principles of logic that Aristotle or Averroes might place on it.[78] More specifically, it contained a list of 219 propositions, including twenty Thomistic propositions, that the bishop had determined to violate the omnipotence of God. The inclusion of the Thomistic propositions badly damaged Thomas's reputation for many years.[79]

Canonization

[edit]

By the 1300s, however, Thomas's theology had begun its rise to prestige. In the Divine Comedy (completed c. 1321), Dante sees the glorified soul of Thomas in the Heaven of the Sun with the other great exemplars of religious wisdom.[80] Dante asserts that Thomas died by poisoning, on the order of Charles of Anjou;[81] Villani cites this belief,[82] and the Anonimo Fiorentino describes the crime and its motive. But the historian Ludovico Antonio Muratori reproduces the account made by one of Thomas's friends, and this version of the story gives no hint of foul play.[83]

When the devil's advocate at his canonization process objected that there were no miracles, one of the cardinals answered, "Tot miraculis, quot articulis"—"there are as many miracles (in his life) as articles (in his Summa)".[84] Fifty years after Thomas's death, on 18 July 1323, Pope John XXII, seated in Avignon, pronounced Thomas a saint.[85]

A monastery at Naples, Italy, near Naples Cathedral, shows a cell in which he supposedly lived.[83] His remains were translated from Fossanova to the Church of the Jacobins in Toulouse, France, on 28 January 1369. Between 1789 and 1974, they were held in the Basilica of Saint-Sernin. In 1974, they were returned to the Church of the Jacobins, where they have remained ever since.

When he was canonized, his feast day was inserted in the General Roman Calendar for celebration on 7 March, the day of his death. Since this date commonly falls within Lent, the 1969 revision of the calendar moved his memorial to 28 January, the date of the translation of his relics to Church of the Jacobins, Toulouse.[86][87]

Thomas Aquinas is honored with a feast day in some churches of the Anglican Communion with a Lesser Festival on 28 January.[88]

The Catholic Church honours Thomas Aquinas as a saint and regards him as the model teacher for those studying for the priesthood. In modern times, under papal directives, the study of his works was long used as a core of the required program of study for those seeking ordination as priests or deacons, as well as for those in religious formation and for other students of the sacred disciplines (philosophy, Catholic theology, church history, liturgy, and canon law).[89]

Doctor of the Church and second scholasticism

[edit]Pope Pius V proclaimed St. Thomas Aquinas a Doctor of the Church on 15 April 1567,[90] and ranked his feast with those of the four great Latin fathers: Ambrose, Augustine of Hippo, Jerome, and Gregory.[83] At the Council of Trent, Thomas had the honour of having his Summa Theologiae placed on the altar alongside the Bible and the Decretals.[79][84] This happened within the historical timeframe of the "second scholasticism", a trend during the 16th and 17th centuries that saw renewed interest in the works of scholars of the 12th, 13th, and 14th centuries, in spite of humanism as a contrary trend. Second scholasticism gave special emphasis to the works of Thomas Aquinas and John Duns Scotus, with more Franciscans following Duns Scotus, and more Dominicans and Carmelites following Thomas.[91] "Thomists", or those following Thomas, included Francisco de Vitoria, Thomas Cajetan, Franciscus Ferrariensis, Domingo de Soto, Domingo Báñez, João Poinsot, the Complutenses and others.

Neo-scholasticism and Catholic Nouvelle théologie

[edit]During the 19th century, a movement that came to be known as neo-scholasticism revived Catholic scholarly interest in scholasticism generally and Thomas in particular, as well as the work of the Thomists of second scholasticism. The systematic work of Thomas was valued in part as a foundation for arguing against early modern philosophers and "modernist" theologians. A good example is Aeterni Patris, the 1879 encyclical by Pope Leo XIII stating that Thomas's theology was a definitive exposition of Catholic doctrine. Leo XIII directed the clergy to take the teachings of Thomas as the basis of their theological positions. Leo also decreed that all Catholic seminaries and universities must teach Thomas's doctrines, and where Thomas did not speak on a topic, the teachers were "urged to teach conclusions that were reconcilable with his thinking." In 1880, Thomas Aquinas was declared the patron saint of all Catholic educational establishments.[83] Similarly, in Pascendi Dominici gregis, the 1907 encyclical by Pope Pius X, the Pope said, "...let Professors remember that they cannot set St. Thomas aside, especially in metaphysical questions, without grave detriment."[92] On 29 June 1923, on the sixth centenary of his canonisation, Pope Pius XI dedicated the encyclical Studiorum Ducem to him.

In response to neo-scholasticism, Catholic scholars who were more sympathetic to modernity gained influence during the early 20th century in the nouvelle théologie movement (meaning "new theology"). It was closely associated with a movement of ressourcement, meaning "back to sources", echoing the phrase "ad fontes" used by Renaissance humanists. Although nouvelle théologie disagreed with neo-scholasticism about modernity, arguing that theology could learn much from modern philosophy and science, their interest in also studying "old" sources meant that they found common ground in their appreciation of scholastics like Thomas Aquinas.[93] The Second Vatican Council generally adopted the stance of the theologians of nouvelle théologie, but the importance of Thomas was a point of agreement.[93] The council's decree Optatam Totius (on the formation of priests, at No. 15), proposed an authentic interpretation of the popes' teaching on Thomism, requiring that the theological formation of priests be done with Thomas Aquinas as teacher.[94]

General Catholic appreciation for Thomas has remained strong in the 20th century, as seen in the praise offered by Pope John Paul II in the 1998 encyclical Fides et ratio,[95] and similarly in Pope Benedict XV's 1921 encyclical Fausto Appetente Die.[96]

Modern philosophical influence

[edit]

Some modern ethicists within the Catholic Church (notably Alasdair MacIntyre) and outside it (notably Philippa Foot) have recently commented on the possible use of Thomas's virtue ethics as a way of avoiding utilitarianism or Kantian "sense of duty" (called deontology).[97] Through the work of twentieth-century philosophers such as Elizabeth Anscombe (especially in her book Intention), Thomas's principle of double effect specifically and his theory of intentional activity generally have been influential.[citation needed]

The cognitive neuroscientist Walter Freeman has proposed that Thomism is the philosophical system explaining cognition that is most compatible with neurodynamics.[98]

Henry Adams's Mont Saint Michel and Chartres ends with a culminating chapter on Thomas, in which Adams calls Thomas an "artist" and constructs an extensive analogy between the design of Thomas's "Church Intellectual" and that of the gothic cathedrals of that period. Erwin Panofsky later would echo these views in Gothic Architecture and Scholasticism (1951).[99]

Thomas's aesthetic theories, especially the concept of claritas, deeply influenced the literary practice of modernist writer James Joyce, who used to extol Thomas as being second only to Aristotle among Western philosophers. Joyce refers to Thomas's doctrines in Elementa philosophiae ad mentem D. Thomae Aquinatis doctoris angelici (1898) of Girolamo Maria Mancini, professor of theology at the Collegium Divi Thomae de Urbe.[100] For example, Mancini's Elementa is referred to in Joyce's Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.[101]

The influence of Thomas's aesthetics also can be found in the works of the Italian semiotician Umberto Eco, who wrote an essay on aesthetic ideas in Thomas (published in 1956 and republished in 1988 in a revised edition).[102]

Modern criticism

[edit]Twentieth-century philosopher Bertrand Russell criticized Thomas's philosophy, stating that:

He does not, like the Platonic Socrates, set out to follow wherever the argument may lead. He is not engaged in an inquiry, the result of which it is impossible to know in advance. Before he begins to philosophize, he already knows the truth; it is declared in the Catholic faith. If he can find apparently rational arguments for some parts of the faith, so much the better; if he cannot, he need only fall back on revelation. The finding of arguments for a conclusion given in advance is not philosophy, but special pleading. I cannot, therefore, feel that he deserves to be put on a level with the best philosophers either of Greece or of modern times.[103]

This criticism is illustrated with the following example: according to Russell, Thomas advocates the indissolubility of marriage "on the ground that the father is useful in the education of the children, (a) because he is more rational than the mother, (b) because, being stronger, he is better able to inflict physical punishment."[104] Even though modern approaches to education do not support these views, "No follower of Saint Thomas would, on that account, cease to believe in lifelong monogamy, because the real grounds of belief are not those which are alleged".[104]

Theology

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Catholic philosophy |

|---|

|

Thomas Aquinas viewed theology, "the sacred doctrine", as a science,[70] by which he meant a field of study in which humanity could learn more by its own efforts (as opposed to being totally dependent on having divine revelation planted into our minds). For Thomas, the raw material data of this field consists of written scripture and the tradition of the Catholic Church. These sources of data were produced by the self-revelation of God to individuals and groups of people throughout history. Faith and reason, being distinct but related, are the two primary tools for processing the data of theology. Thomas believed both were necessary—or, rather, that the confluence of both was necessary—for one to obtain true knowledge of God.[70]

Thomas blended Greek philosophy and Christian doctrine by suggesting that rational thinking and the study of nature, like revelation, were valid ways to understand truths pertaining to God. According to Thomas, God reveals himself through nature, so to study nature is to study God. The ultimate goals of theology, in Thomas's mind, are to use reason to grasp the truth about God and to experience salvation through that truth. The central thought is "gratia non tollit naturam, sed perficit" ('grace does not destroy nature, but perfects it').[70]

Revelation

[edit]Thomas believed that truth is known through reason, rationality (natural revelation) and faith (supernatural revelation). Supernatural revelation has its origin in the inspiration of the Holy Spirit and is made available through the teaching of the prophets, summed up in Holy Scripture, and transmitted by the Magisterium, the sum of which is called "Tradition". Natural revelation is the truth available to all people through their human nature and powers of reason. For example, he felt this applied to rational ways to know the existence of God.

Though one may deduce the existence of God and his Attributes (Unity, Truth, Goodness, Power, Knowledge) through reason, certain specifics may be known only through the special revelation of God through Jesus Christ. The major theological components of Christianity, such as the Trinity, the Incarnation, and charity are revealed in the teachings of the church and the scriptures and may not otherwise be deduced.[105] However, Thomas also makes a distinction between "demonstrations" of sacred doctrines and the "persuasiveness" of those doctrines.[106] The former is akin to something like "certainty", whereas the latter is more probabilistic in nature.[106]

In other words, Thomas thought Christian doctrines were "fitting" to reason (i.e. reasonable), even though they cannot be demonstrated beyond a reasonable doubt.[106] In fact, the Summa Theologica is filled with examples of Thomas arguing that we would expect certain Christian doctrines to be true, even though these expectations are not demonstrative (i.e. 'fitting' or reasonable).[107] For example, Thomas argues that we would expect God to become incarnate, and we would expect a resurrected Christ to not stay on Earth.[107][108]

Reconciling faith and reason

[edit]According to Thomas, faith and reason complement rather than contradict each other, each giving different views of the same truth. A discrepancy between faith and reason arises from a shortcoming of either natural science or scriptural interpretation. Faith can reveal a divine mystery that eludes scientific observation. On the other hand, science can suggest where fallible humans misinterpret a scriptural metaphor as a literal statement of fact.[109]

God

[edit]Augustine of Hippo's reflection on divine essentiality or essentialist theology would influence Richard of St. Victor, Alexander of Hales, and Bonaventure. By this method, the essence of God is defined by what God is, and also by describing what God is not (negative theology). Thomas took the text of Exodus beyond the explanation of essential theology. He bridged the gap of understanding between the being of essence and the being of existence. In Summa Theologica, the way is prepared with the proofs for the existence of God. All that remained was to recognize the God of Exodus as having the nature of "Him Who is the supreme act of being". God is simple, there is no composition in God. In this regard, Thomas relied on Boethius who in turn followed the path of Platonism, something Thomas usually avoided.[110]

The conclusion was that the meaning of "I Am Who I Am" is not an enigma to be answered, but a statement of the essence of God. This is the discovery of Thomas: the essence of God is not described by negative analogy, but the "essence of God is to exist". This is the basis of "existential theology" and leads to what Gilson calls the first and only existential philosophy. In Latin, this is called "Haec Sublimis Veritas", "the sublime truth". The revealed essence of God is to exist, or in the words of Thomas, "I am the pure Act of Being". This has been described as the key to understanding Thomism. Thomism has been described (as a philosophical movement), as either the emptiest or the fullest of philosophies.[110]

Creation

[edit]

As a Catholic, Thomas believed that God was the "maker of heaven and earth, of all that is visible and invisible." But he thought that this fact can be proved by natural reason; indeed, in showing that it is necessary that any existent being has been created by God, he uses only philosophical arguments, based on his metaphysics of participation.[111] He also maintains that God creates ex nihilo, from nothing, that is he does not make use of any preexisting matter.[112] On the other hand, Thomas thought that the fact that the world started to exist by God's creation and is not eternal is only known to us by faith; it cannot be proved by natural reason.[113]

Like Aristotle, Thomas posited that life could form from non-living material or plant life:

Since the generation of one thing is the corruption of another, it was not incompatible with the first formation of things, that from the corruption of the less perfect the more perfect should be generated. Hence animals generated from the corruption of inanimate things, or of plants, may have been generated then.[114]

Additionally, Thomas considered Empedocles's theory that various mutated species emerged at the dawn of Creation. Thomas reasoned that these species were generated through mutations in animal sperm, and argued that they were not unintended by nature; rather, such species were simply not intended for perpetual existence. That discussion is found in his commentary on Aristotle's Physics:

The same thing is true of those substances Empedocles said were produced at the beginning of the world, such as the 'ox-progeny', i.e., half ox and half-man. For if such things were not able to arrive at some end and final state of nature so that they would be preserved in existence, this was not because nature did not intend this [a final state], but because they were not capable of being preserved. For they were not generated according to nature, but by the corruption of some natural principle, as it now also happens that some monstrous offspring are generated because of the corruption of seed.[115]

Nature of God

[edit]Thomas believed that the existence of God is self-evident in itself, but not to us. "Therefore, I say that this proposition, "God exists", of itself is self-evident, for the predicate is the same as the subject ... Now because we do not know the essence of God, the proposition is not self-evident to us; but needs to be demonstrated by things that are more known to us, though less known in their nature—namely, by effects."[116]

Thomas believed that the existence of God can be demonstrated. Briefly in the Summa Theologiae and more extensively in the Summa contra Gentiles, he considered in great detail five arguments for the existence of God, widely known as the quinque viae (Five Ways).

- Motion: Some things undoubtedly move, though cannot cause their own motion. Since, as Thomas believed, there can be no infinite chain of causes of motion, there must be a First Mover not moved by anything else, and this is what everyone understands by God.

- Causation: As in the case of motion, nothing can cause itself, and an infinite chain of causation is impossible, so there must be a First Cause, called God.

- Existence of necessary and the unnecessary: Our experience includes things certainly existing but apparently unnecessary. Not everything can be unnecessary, for then once there was nothing and there would still be nothing. Therefore, we are compelled to suppose something that exists necessarily, having this necessity only from itself; in fact itself the cause for other things to exist.

- Gradation: If we can notice a gradation in things in the sense that some things are more hot, good, etc., there must be a superlative that is the truest and noblest thing, and so most fully existing. This then, we call God.[b]

- Ordered tendencies of nature: A direction of actions to an end is noticed in all bodies following natural laws. Anything without awareness tends to a goal under the guidance of one who is aware. This we call God.[c][117]

Thomas was receptive to and influenced by Avicenna's Proof of the Truthful.[118] Concerning the nature of God, Thomas, like Avicenna felt the best approach, commonly called the via negativa, was to consider what God is not. This led him to propose five statements about the divine qualities:

- God is simple, without composition of parts, such as body and soul, or matter and form.[119]

- God is perfect, lacking nothing. That is, God is distinguished from other beings on account of God's complete actuality.[120] Thomas defined God as the Ipse Actus Essendi subsistens, subsisting act of being.[121]

- God is infinite. That is, God is not finite in the ways that created beings are physically, intellectually, and emotionally limited. This infinity is to be distinguished from infinity of size and infinity of number.[122]

- God is immutable, incapable of change on the levels of God's essence and character.[123]

- God is one, without diversification within God's self. The unity of God is such that God's essence is the same as God's existence. In Thomas's words, "in itself the proposition 'God exists' is necessarily true, for in it subject and predicate are the same."[124]

Nature of sin

[edit]Following Augustine of Hippo, Thomas defines sin as "a word, deed, or desire, contrary to the eternal law."[125] It is important to note the analogous nature of law in Thomas's legal philosophy. Natural law is an instance or instantiation of eternal law. Because natural law is what human beings determine according to their own nature (as rational beings), disobeying reason is disobeying natural law and eternal law. Thus eternal law is logically prior to reception of either "natural law" (that determined by reason) or "divine law" (that found in the Old and New Testaments). In other words, God's will extends to both reason and revelation. Sin is abrogating either one's own reason, on the one hand, or revelation on the other, and is synonymous with "evil" (privation of good, or privatio boni[126]). Thomas, like all Scholastics, generally argued that the findings of reason and data of revelation cannot conflict, so both are a guide to God's will for human beings.

Nature of the Trinity

[edit]Thomas argued that God, while perfectly united, also is perfectly described by Three Interrelated Persons. These three persons (Father, Son, and Holy Spirit) are constituted by their relations within the essence of God. Thomas wrote that the term "Trinity" "does not mean the relations themselves of the Persons, but rather the number of persons related to each other; and hence it is that the word in itself does not express regard to another."[127] The Father generates the Son (or the Word) by the relation of self-awareness. This eternal generation then produces an eternal Spirit "who enjoys the divine nature as the Love of God, the Love of the Father for the Word."

This Trinity exists independently from the world. It transcends the created world, but the Trinity also decided to give grace to human beings. This takes place through the Incarnation of the Word in the person of Jesus Christ and through the indwelling of the Holy Spirit within those who have experienced salvation by God; according to Aidan Nichols.[128]

Prima causa (first cause)

[edit]Thomas's five proofs for the existence of God take some of Aristotle's assertions concerning the principles of being. For God as prima causa ("first cause") comes from Aristotle's concept of the unmoved mover and asserts that God is the ultimate cause of all things.[129]

Nature of Jesus Christ

[edit]

In the Summa Theologica, Thomas begins his discussion of Jesus Christ by recounting the biblical story of Adam and Eve and by describing the negative effects of original sin. The purpose of Christ's Incarnation was to restore human nature by removing the contamination of sin, which humans cannot do by themselves. "Divine Wisdom judged it fitting that God should become man, so that thus one and the same person would be able both to restore man and to offer satisfaction."[130] Thomas argued in favour of the satisfaction view of atonement; that is, that Jesus Christ died "to satisfy for the whole human race, which was sentenced to die on account of sin."[131]

Thomas argued against several specific contemporary and historical theologians who held differing views about Christ. In response to Photinus, Thomas stated that Jesus was truly divine and not simply a human being. Against Nestorius, who suggested that the Son of God was merely conjoined to the man Christ, Thomas argued that the fullness of God was an integral part of Christ's existence. However, countering Apollinaris' views, Thomas held that Christ had a truly human (rational) soul, as well. This produced a duality of nature in Christ. Thomas argued against Eutyches that this duality persisted after the Incarnation. Thomas stated that these two natures existed simultaneously yet distinguishably in one real human body, unlike the teachings of Manichaeus and Valentinus.[132]

With respect to Paul's assertion that Christ, "though he was in the form of God ... emptied himself" (Philippians 2:6–7) in becoming human, Thomas offered an articulation of divine kenosis that has informed much subsequent Catholic Christology. Following the Council of Nicaea, Augustine of Hippo, as well as the assertions of Scripture, Thomas held the doctrine of divine immutability.[133][134][135] Hence, in becoming human, there could be no change in the divine person of Christ. For Thomas, "the mystery of Incarnation was not completed through God being changed in any way from the state in which He had been from eternity, but through His having united Himself to the creature in a new way, or rather through having united it to Himself."[136]

Similarly, Thomas explained that Christ "emptied Himself, not by putting off His divine nature, but by assuming a human nature."[137] For Thomas, "the divine nature is sufficiently full, because every perfection of goodness is there. But human nature and the soul are not full, but capable of fulness, because it was made as a slate not written upon. Therefore, human nature is empty."[137] Thus, when Paul indicates that Christ "emptied himself" this is to be understood in light of his assumption of a human nature.

In short, "Christ had a real body of the same nature of ours, a true rational soul, and, together with these, perfect Deity". Thus, there is both unity (in his one hypostasis) and composition (in his two natures, human and Divine) in Christ.[138]

I answer that, The Person or hypostasis of Christ may be viewed in two ways. First as it is in itself, and thus it is altogether simple, even as the Nature of the Word. Secondly, in the aspect of person or hypostasis to which it belongs to subsist in a nature; and thus the Person of Christ subsists in two natures. Hence though there is one subsisting being in Him, yet there are different aspects of subsistence, and hence He is said to be a composite person, insomuch as one being subsists in two.[139]

Echoing Athanasius of Alexandria, he said that "The only begotten Son of God ... assumed our nature, so that he, made man, might make men gods."[140]

Goal of human life

[edit]

Thomas Aquinas identified the goal of human existence as union and eternal fellowship with God. This goal is achieved through the beatific vision, in which a person experiences perfect, unending happiness by seeing the essence of God. The vision occurs after death as a gift from God to those who in life experienced salvation and redemption through Christ.

The goal of union with God has implications for the individual's life on earth. Thomas stated that an individual's will must be ordered toward the right things, such as charity, peace, and holiness. He saw this orientation as also the way to happiness. Indeed, Thomas ordered his treatment of the moral life around the idea of happiness. The relationship between will and goal is antecedent in nature "because rectitude of the will consists in being duly ordered to the last end [that is, the beatific vision]." Those who truly seek to understand and see God will necessarily love what God loves. Such love requires morality and bears fruit in everyday human choices.[141]

Treatment of heretics

[edit]Thomas Aquinas belonged to the Dominican Order (formally Ordo Praedicatorum, the Order of Preachers) which began as an order dedicated to the conversion of the Albigensians and other heterodox factions, at first by peaceful means; later the Albigensians were dealt with by means of the Albigensian Crusade. In the Summa Theologiae, he wrote:

With regard to heretics two points must be observed: one, on their own side; the other, on the side of the Church. On their own side there is the sin, whereby they deserve not only to be separated from the Church by excommunication, but also to be severed from the world by death. For it is a much graver matter to corrupt the faith that quickens the soul, than to forge money, which supports temporal life. Wherefore if forgers of money and other evil-doers are forthwith condemned to death by the secular authority, much more reason is there for heretics, as soon as they are convicted of heresy, to be not only excommunicated but even put to death. On the part of the Church, however, there is mercy, which looks to the conversion of the wanderer, wherefore she condemns not at once, but "after the first and second admonition", as the Apostle directs: after that, if he is yet stubborn, the Church no longer hoping for his conversion, looks to the salvation of others, by excommunicating him and separating him from the Church, and furthermore delivers him to the secular tribunal to be exterminated thereby from the world by death.[142]

Heresy was a capital offence against the secular law of most European countries of the 13th century. Kings and emperors, even those at war with the papacy, listed heresy first among the crimes against the state. Kings claimed power from God according to the Christian faith. Often enough, especially in that age of papal claims to universal worldly power, the rulers' power was tangibly and visibly legitimated directly through coronation by the pope.

Simple theft, forgery, fraud, and other such crimes were also capital offences; Thomas's point seems to be that the gravity of this offence, which touches not only the material goods but also the spiritual goods of others, is at least the same as forgery. Thomas's suggestion specifically demands that heretics be handed to a "secular tribunal" rather than magisterial authority. That Thomas specifically says that heretics "deserve ... death" is related to his theology, according to which all sinners have no intrinsic right to life ("For the wages of sin is death; but the free gift of God is eternal life in Christ Jesus our Lord"[143]). Although the life of a heretic who repents should be spared, the former heretic should be executed if he relapses into heresy. Thomas elaborates on his opinion regarding heresy in the next article, when he says:

In God's tribunal, those who return are always received, because God is a searcher of hearts, and knows those who return in sincerity. But the Church cannot imitate God in this, for she presumes that those who relapse after being once received, are not sincere in their return; hence she does not debar them from the way of salvation, but neither does she protect them from the sentence of death. For this reason the Church not only admits to Penance those who return from heresy for the first time, but also safeguards their lives, and sometimes by dispensation, restores them to the ecclesiastical dignities which they may have had before, should their conversion appear to be sincere: we read of this as having frequently been done for the good of peace. But when they fall again, after having been received, this seems to prove them to be inconstant in faith, wherefore when they return again, they are admitted to Penance, but are not delivered from the pain of death.[144]

For Jews, Thomas argues for toleration of both their persons and their religious rites.[145]

Forced baptism of children of Jews and heretics

[edit]The position taken by Thomas was that if children were being reared in error, the Church had no authority to intervene. From Summa Theologica II-II Q. 10 Art. 12:

- Injustice should be done to no man. Now it would be an injustice to Jews if their children were to be baptized against their will, since they would lose the rights of parental authority over their children as soon as these were Christians. Therefore, these should not be baptized against their parent's will. The custom of the Church has been given very great authority and ought to be jealously observed in all things, since the very doctrine of Catholic Doctors derives its authority from the Church. Hence we ought to abide by the authority of the Church rather than that of an Augustine or a Jerome or any doctor whatever. Now it was never the custom of the Church to baptize the children of Jews against the will of their parents. There are two reasons for this custom. One is on account of the danger to faith. For children baptized before coming into the use of reason, might easily be persuaded by their parents to renounce what they had unknowingly embraced; and this would be detrimental to the faith. The other reason is that it is against natural justice. For a child is by nature part of its father: at first, it is not distinct from its parents as to its body, so long as it is enfolded within the mother's womb and later on after birth, and before it has the use of free will, it is enfolded in the care of its parents, like a spiritual womb. So long as a man does not have the use of reason, he is no different from an irrational animal. Hence, it would be contrary to natural justice, if a child, before coming to the use of reason, were to be taken away from its parent's custody, or anything done against its parent's wish.

The question was again addressed by Thomas in Summa Theologica III Q. 68 Art. 10:

- It is written in the Decretals (Dist. xiv), quoting the Council of Toledo: In regard to the Jews the holy synod commands that henceforth none of them be forced to believe; for such are not to be saved against their will, but willingly, that their righteousness may be without flaw. Children of non-believers either have the use of reason or they have not. If they have, then they already begin to control their own actions, in things that are of Divine or natural law. And therefore, of their own accord, and against the will of their parents, they can receive Baptism, just as they can contract in marriage. Consequently, such can be lawfully advised and persuaded to be baptized. If, however, they have not yet the use of free-will, according to the natural law they are under the care of their parents as long as they cannot look after themselves. For which reason we say that even the children of the ancients were saved through the faith of their parents.

The issue was discussed in a papal bull by Pope Benedict XIV (1747) where both schools were addressed. The pope noted that the position of Aquinas had been more widely held among theologians and canon lawyers, than that of John Duns Scotus.[146]

Magic and its practitioners

[edit]Regarding magic, Thomas wrote that:

- only God can perform miracles, create and transform.[147]

- angels and demons ("spiritual substances") may do wonderful things, but they are not miracles and merely use natural things as instruments.[148]

- any efficacy of magicians does not come from the power of particular words, or celestial bodies, or special figures, or sympathetic magic, but by bidding (ibid., 105)

- "demons" are intellective substances which were created good and have chosen to be bad, it is these who are bid.[149]

- if there is some transformation that could not occur in nature it is either the demon working on human imagination or arranging a fake.[150]

A mention of witchcraft appears in the Summa Theologicae[151] and concludes that the church does not treat temporary or permanent impotence attributed to a spell any differently to that of natural causes, as far as an impediment to marriage.

Under the canon Episcopi, church doctrine held that witchcraft was not possible and any practitioners of sorcery were deluded and their acts an illusion. Thomas Aquinas was cited in a new doctrine that included the belief in witches. This was a departure from the teachings of his master Albertus Magnus whose doctrine was based in the Episcopi.[152] "To what extent Dominican inquisitors such as Heinrich Kramer really found support in Thomas is irrelevant in this context, thus associating Thomas's name with the whole aspect of witchcraft and the persecution of witches."[153]

The famous 15th-century witch-hunter's manual, the Malleus Maleficarum, also written by a member of the Dominican Order, begins by quoting Thomas Aquinas ("Commentary on Pronouncements" Sent.4.34.I.Co.) refuting the Episcopi and goes on to cite Thomas Aquinas over a hundred times.[154] Promoters of the witch hunts that followed often quoted Thomas more than any other source.[152] "Thomas Aquinas's statements remain essentially theoretical and lack any direct relation to the subsequent persecution of witches."[153]

Thoughts on the afterlife and resurrection

[edit]

A grasp of Thomas's psychology is essential for understanding his beliefs about the afterlife and resurrection. Thomas, following church doctrine, accepts that the soul continues to exist after the death of the body. Because he accepts that the soul is the form of the body, then he also must believe that the human being, like all material things, is form-matter composite. The substantial form (the human soul) configures prime matter (the physical body) and is the form by which a material composite belongs to that species it does; in the case of human beings, that species is a rational animal.[155] So, a human being is a matter-form composite that is organized to be a rational animal. Matter cannot exist without being configured by form, but form can exist without matter—which allows for the separation of soul from body. Thomas says that the soul shares in the material and spiritual worlds, and so has some features of matter and other, immaterial, features (such as access to universals). The human soul is different from other material and spiritual things; it is created by God, but also comes into existence only in the material body.

Human beings are material, but the human person can survive the death of the body through the continued existence of the soul, which persists. The human soul straddles the spiritual and material worlds, and is both a configured subsistent form as well as a configurer of matter into that of a living, bodily human.[156] Because it is spiritual, the human soul does not depend on matter and may exist separately. Because the human being is a soul-matter composite, the body has a part in what it is to be human. Perfected human nature consists in the human dual nature, embodied and intellecting.

Resurrection appears to require dualism, which Thomas rejects. Yet Thomas believes the soul persists after the death and corruption of the body, and is capable of existence, separated from the body between the time of death and the resurrection of the flesh. Thomas believes in a different sort of dualism, one guided by Christian scripture. Thomas knows that human beings are essentially physical, but physicality has a spirit capable of returning to God after life.[157] For Thomas, the rewards and punishment of the afterlife are not only spiritual. Because of this, resurrection is an important part of his philosophy on the soul. The human is fulfilled and complete in the body, so the hereafter must take place with souls enmattered in resurrected bodies. In addition to spiritual reward, humans can expect to enjoy material and physical blessings. Because Thomas's soul requires a body for its actions, during the afterlife, the soul will also be punished or rewarded in corporeal existence.

Thomas states clearly his stance on resurrection, and uses it to back up his philosophy of justice; that is, the promise of resurrection compensates Christians who suffered in this world through a heavenly union with the divine. He says, "If there is no resurrection of the dead, it follows that there is no good for human beings other than in this life."[158] Resurrection provides the impetus for people on earth to give up pleasures in this life. Thomas believes the human who prepared for the afterlife both morally and intellectually will be rewarded more greatly; however, all reward is through the grace of God. Thomas insists beatitude will be conferred according to merit, and will render the person better able to conceive the divine.

Thomas accordingly believes punishment is directly related to earthly, living preparation and activity as well. Thomas's account of the soul focuses on epistemology and metaphysics, and because of this, he believes it gives a clear account of the immaterial nature of the soul. Thomas conservatively guards Christian doctrine and thus maintains physical and spiritual reward and punishment after death. By accepting the essentiality of both body and soul, he allows for a Heaven and Hell described in scripture and church dogma.

Philosophy

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Thomas Aquinas |

|---|

|

Thomas Aquinas was a theologian and a Scholastic philosopher.[159] He never considered himself a philosopher, and criticized philosophers whom he saw as pagans, for always "falling short of the true and proper wisdom to be found in Christian revelation".[160] With this in mind, Thomas did have respect for Aristotle, so much so that in the Summa, he often cites Aristotle simply as "the Philosopher", a designation frequently used at that time. However, Thomas "never compromised Christian doctrine by bringing it into line with current Aristotelianism; rather, he modified and corrected the latter whenever it clashed with Christian belief".[161]

Much of Thomas's work bears upon philosophical topics, and in this sense may be characterized as philosophical. His philosophical thought has exerted enormous influence on subsequent Christian theology, especially that of the Catholic Church, extending to Western philosophy in general.

Commentaries on Aristotle

[edit]Thomas Aquinas wrote several important commentaries on Aristotle's works, including On the Soul, On Interpretation, Posterior Analytics, Nicomachean Ethics, Physics and Metaphysics. His work is associated with William of Moerbeke's translations of Aristotle from Greek into Latin.

Epistemology

[edit]Thomas Aquinas believed "that for the knowledge of any truth whatsoever man needs divine help, that the intellect may be moved by God to its act."[162] However, he believed that human beings have the natural capacity to know many things without special divine revelation, even though such revelation occurs from time to time, "especially in regard to such (truths) as pertain to faith."[163] But this is the light that is given to man by God according to man's nature: "Now every form bestowed on created things by God has power for a determined act[uality], which it can bring about in proportion to its own proper endowment; and beyond which it is powerless, except by a superadded form, as water can only heat when heated by the fire. And thus the human understanding has a form, viz. intelligible light, which of itself is sufficient for knowing certain intelligible things, viz. those we can come to know through the senses."[163]

Ethics

[edit]Thomas was aware that the Albigensians and the Waldensians challenged moral precepts concerning marriage and ownership of private property and that challenges could ultimately be resolved only by logical arguments based on self-evident norms. He accordingly argued, in the Summa Theologiae, that just as the first principle of demonstration is the self-evident principle of noncontradiction ("the same thing cannot be affirmed and denied at the same time"), the first principle of action is the self-evident Bonum precept ("good is to be done and pursued and evil avoided").[164]

This natural law precept prescribes doing and pursuing what reason knows is good while avoiding evil. Reason knows what is objectively good because good is naturally beneficial and evil is the contrary. To explain goods that are naturally self-evident, Thomas divides them into three categories: substantial goods of self-preservation desired by all; the goods common to both animals and humans, such as procreation and education of offspring; and goods characteristic of rational and intellectual beings, such as living in community and pursuing the truth about God.[165]

To will such natural goods to oneself and to others is to love. Accordingly, Thomas states that the love precept obligating loving God and neighbour are "the first general principles of the natural law, and are self-evident to human reason, either through nature or through faith. Wherefore all the precepts of the decalogue are referred to these, as conclusions to general principles."[166][167]

To so focus on lovingly willing good is to focus natural law on acting virtuously. In his Summa Theologiae, Thomas wrote:

Virtue denotes a certain perfection of a power. Now a thing's perfection is considered chiefly in regard to its end. But the end of power is act. Wherefore power is said to be perfect, according as it is determinate to its act.[168]

Thomas emphasized that "Synderesis is said to be the law of our mind, because it is a habit containing the precepts of the natural law, which are the first principles of human actions."[169][170]

According to Thomas "... all acts of virtue are prescribed by the natural law: since each one's reason naturally dictates to him to act virtuously. But if we speak of virtuous acts, considered in themselves, i.e., in their proper species, thus not all virtuous acts are prescribed by the natural law: for many things are done virtuously, to which nature does not incline at first; but that, through the inquiry of reason, have been found by men to be conducive to well living." Therefore, we must determine if we are speaking of virtuous acts as under the aspect of virtuous or as an act in its species.[171]

Thomas defined the four cardinal virtues as prudence, temperance, justice, and fortitude. The cardinal virtues are natural and revealed in nature, and they are binding on everyone. There are, however, three theological virtues: faith, hope, and charity. Thomas also describes the virtues as imperfect (incomplete) and perfect (complete) virtues. A perfect virtue is any virtue with charity, charity completes a cardinal virtue. A non-Christian can display courage, but it would be courage with temperance. A Christian would display courage with charity. These are somewhat supernatural and are distinct from other virtues in their object, namely, God:

Now the object of the theological virtues is God Himself, Who is the last end of all, as surpassing the knowledge of our reason. On the other hand, the object of the intellectual and moral virtues is something comprehensible to human reason. Therefore the theological virtues are specifically distinct from the moral and intellectual virtues.[172]

Thomas Aquinas wrote "[Greed] is a sin against God, just as all mortal sins, in as much as man condemns things eternal for the sake of temporal things."[173]

Furthermore, in his Treatise on Law, Thomas distinguished four kinds of law: eternal, natural, human, and divine. Eternal law is the decree of God that governs all creation: "That Law which is the Supreme Reason cannot be understood to be otherwise than unchangeable and eternal."[174] Natural law is the human "participation" in the eternal law and is discovered by reason.[175] Natural law is based on "first principles":

. . . this is the first precept of the law, that good is to be done and promoted, and evil is to be avoided. All other precepts of the natural law are based on this . . .[176]

Whether the natural law contains several precepts, or one only is explained by Thomas, "All the inclinations of any parts whatsoever of human nature, e.g., of the concupiscible and irascible parts, in so far as they are ruled by reason, belong to the natural law, and are reduced to one first precept, as stated above: so that the precepts of the natural law are many in themselves, but are based on one common foundation."[177]

The desires to live and to procreate are counted by Thomas among those basic (natural) human values on which all human values are based. According to Thomas, all human tendencies are geared towards real human goods. In this case, the human nature in question is marriage, the total gift of oneself to another that ensures a family for children and a future for mankind.[178] He defined the dual inclination of the action of love: "towards the good which a man wishes to someone (to himself or to another) and towards that to which he wishes some good".[179]

Concerning Human Law, Thomas concludes, "... that just as, in the speculative reason, from naturally known indemonstrable principles, we draw the conclusions of the various sciences, the knowledge of which is not imparted to us by nature, but acquired by the efforts of reason, so to it is from the precepts of the natural law, as from general and indemonstrable principles, that human reason needs to proceed to the more particular determination of certain matters. These particular determinations, devised by human reason, are called human laws, provided the other essential conditions of law be observed ..." Human law is positive law: the natural law applied by governments to societies.[171]

Natural and human law is not adequate alone. The need for human behaviour to be directed made it necessary to have Divine law. Divine law is the specially revealed law in the scriptures. Thomas quotes, "The Apostle says (Hebrews 7.12): The priesthood being translated, it is necessary that a translation also be made of the law. But the priesthood is twofold, as stated in the same passage, viz, the levitical priesthood, and the priesthood of Christ. Therefore, the Divine law is twofold, namely, the Old Law and the New Law."[180]

Thomas also greatly influenced Catholic understandings of mortal and venial sins.

Thomas Aquinas refers to animals as dumb and that the natural order has declared animals for man's use. Thomas denied that human beings have any duty of charity to animals because they are not persons. Otherwise, it would be unlawful to kill them for food. But humans should still be charitable to them, for "cruel habits might carry over into our treatment of human beings."[181][182]

Thomas contributed to economic thought as an aspect of ethics and justice. He dealt with the concept of a just price, normally its market price or a regulated price sufficient to cover seller costs of production. He argued it was immoral for sellers to raise their prices simply because buyers were in pressing need of a product.[183][184]

Political order

[edit]Thomas's theory of political order became highly influential. He sees man as a social being who lives in a community and interacts with its other members. That leads, among other things, to the division of labour.

Thomas made a distinction between a good man and a good citizen, which was important to the development of libertarian theory. That indicates, in the eyes of the atheist libertarian writer George H. Smith, that the sphere of individual autonomy was one which the state could not interfere with.[185]

Thomas thought that monarchy was the best form of government because a monarch does not have to form compromises with other persons. Thomas, however, held that monarchy in only a very specific sense was the best form of government—only when the king was virtuous is it the best form; otherwise if the monarch is vicious it is the worst kind (see De Regno I, Ch. 2). Moreover, according to Thomas, oligarchy degenerates more easily into tyranny than monarchy. To prevent a king from becoming a tyrant, his political powers must be curbed. Unless an agreement of all persons involved can be reached, a tyrant must be tolerated, as otherwise, the political situation could deteriorate into anarchy, which would be even worse than tyranny. In his political work De Regno, Thomas subordinated the political power of the king to the primacy of the divine and human law of God the creator. For example, he affirmed:

Just as the government of a king is the best, so the government of a tyrant is the worst.

— "De Regno, Ch. 4, n. 21" (in Latin and English).

It is plain, therefore, from what has been said, that a king is one who rules the people of one city or province, and rules them for the common good.

— "De Regno, Ch. 2, n. 15" (in Latin and English).

According to Thomas, monarchs are God's representatives in their territories, but the church, represented by the popes, is above the kings in matters of doctrine and ethics. As a consequence, worldly rulers are obliged to adapt their laws to the Catholic Church's doctrines and determinations.

Thomas said slavery was not the natural state of man.[186] He also held that a slave is by nature equal to his master (Summa Theologiae Supplement, Q52, A2, ad 1). He distinguished between 'natural slavery', which is for the benefit of both master and slave, and 'servile slavery', which removes all autonomy from the slave and is, according to Thomas, worse than death.[187] Aquinas' doctrines of the Fair Price,[188] of the right of tyrannicide and of the equality of all the baptized sons of God in the Communion of saints established a limit to the political power to prevent it from degenerating into tyranny. This system had a concern in the Protestant opposition to the Catholic Church and in "disinterested" replies to Thomism carried out by Kant and by Spinoza.

Death penalty

[edit]In Summa Contra Gentiles, Book 3, Chapter 146, which was written by Thomas prior to writing the Summa Theologica, Thomas allowed the judicial death penalty. He stated:[189]

[M]en who are in authority over others do no wrong when they reward the good and punish the evil.

[…] for the preservation of concord among men it is necessary that punishments be inflicted on the wicked. Therefore, to punish the wicked is not in itself evil.

Moreover, the common good is better than the particular good of one person. So, the particular good should be removed in order to preserve the common good. But the life of certain pestiferous men is an impediment to the common good which is the concord of human society. Therefore, certain men must be removed by death from the society of men.

Furthermore, just as a physician looks to health as the end in his work, and health consists in the orderly concord of humors, so, too, the ruler of a state intends peace in his work, and peace consists in "the ordered concord of citizens." Now, the physician quite properly and beneficially cuts off a diseased organ if the corruption of the body is threatened because of it. Therefore, the ruler of a state executes pestiferous men justly and sinlessly in order that the peace of the state may not be disrupted.

However, in the same discussion:

The unjust execution of men is prohibited…Killing which results from anger is prohibited…The execution of the wicked is forbidden wherever cannot be done without danger to the good.

Just war

[edit]While it would be contradictory to speak of a "just schism", a "just brawling" or a "just sedition", the word "war" permits sub-classification into good and bad kinds. Thomas Aquinas, centuries after Augustine of Hippo, used the authority of Augustine's arguments in an attempt to define the conditions under which a war could be just.[190] He laid these out in his work Summa Theologica:

- First, war must occur for a good and just purpose rather than the pursuit of wealth or power.

- Second, just war must be waged by a properly instituted authority such as the state.

- Third, peace must be a central motive even in the midst of violence.[191]

Psychology and anthropology

[edit]Thomas Aquinas maintains that a human is a single material substance. He understands the soul as the form of the body, which makes a human being the composite of the two. Thus, only living, form-matter composites can truly be called human; dead bodies are "human" only analogously. One actually existing substance comes from body and soul. A human is a single material substance, but still should be understood as having an immaterial soul, which continues after bodily death.

In his Summa Theologiae Thomas states his position on the nature of the soul; defining it as "the first principle of life".[192] The soul is not corporeal, or a body; it is the act of a body. Because the intellect is incorporeal, it does not use the bodily organs, as "the operation of anything follows the mode of its being".[193]

According to Thomas, the soul is not matter, not even incorporeal or spiritual matter. If it were, it would not be able to understand universals, which are immaterial. A receiver receives things according to the receiver's own nature, so for the soul (receiver) to understand (receive) universals, it must have the same nature as universals. Yet, any substance that understands universals may not be a matter-form composite. So, humans have rational souls, which are abstract forms independent of the body. But a human being is one existing, single material substance that comes from body and soul: that is what Thomas means when he writes that "something one in nature can be formed from an intellectual substance and a body", and "a thing one in nature does not result from two permanent entities unless one has the character of substantial form and the other of matter."[194]

Economics

[edit]Thomas Aquinas addressed most economic questions within the framework of justice, which he contended was the highest of the moral virtues.[195] He says that justice is "a habit whereby man renders to each his due by a constant and perpetual will."[196] He argued that this concept of justice has its roots in natural law. Joseph Schumpeter, in his History of Economic Analysis, concluded that "All the economic questions put together matters less to him than did the smallest point of theological or philosophical doctrine, and it is only where economic phenomena raise questions of moral theology that he touches upon them at all."[197]

Modern Western views concerning capitalism, unfair labor practice, living wage, price gouging, monopolies, fair trade practices, and predatory pricing, inter alia, are remnants of the inculcation of Aquinas' interpretation of natural moral law.[198]

Just price

[edit]Thomas Aquinas distinguished the just, or natural, price of a good from that price which manipulates another party. He determines the just price from a number of things. First, the just price must be relative to the worth of the good. Thomas held that the price of a good measures its quality: "the quality of a thing that comes into human use is measured by the price given for it".[199] The price of a good, measured by its worth, is determined by its usefulness to man. This worth is subjective because each good has a different level of usefulness to every man. The price should reflect the current value of a good according to its usefulness to man. "Gold and silver are costly not only on account of the usefulness of the vessels and other like things made from them, but also on account of the excellence and purity of their substance."[200]

Social justice

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Integralism |

|---|

|

Thomas defines distributive justice as follows:[201]