Cold Mountain (film)

| Cold Mountain | |

|---|---|

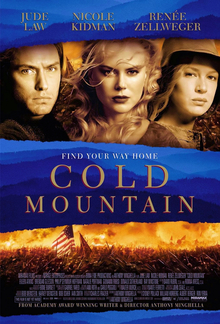

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Anthony Minghella |

| Screenplay by | Anthony Minghella |

| Based on | Cold Mountain by Charles Frazier |

| Produced by | |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | John Seale |

| Edited by | Walter Murch |

| Music by | Gabriel Yared |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Miramax Films |

Release date |

|

Running time | 154 minutes |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | $79 million[2] |

| Box office | $173 million[2] |

Cold Mountain is a 2003 epic period war drama film written and directed by Anthony Minghella. The film is based on the bestselling 1997 novel by Charles Frazier.[3] It stars Jude Law, Nicole Kidman, and Renée Zellweger with Eileen Atkins, Brendan Gleeson, Kathy Baker, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Natalie Portman, Jack White, Giovanni Ribisi, Donald Sutherland, and Ray Winstone in supporting roles. The film tells the story of a wounded deserter from the Confederate army close to the end of the American Civil War, who journeys home to reunite with the woman he loves. The film was a co-production of companies in Italy, Romania, and the United States.

Cold Mountain was released theatrically on December 25, 2003, by Miramax Films. It emerged a critical and commercial success, grossing over $173 million. It received seven nominations at the 76th Academy Awards, including Best Actor (Law), with Zellweger winning Best Supporting Actress.

Plot

[edit]When North Carolina secedes from the Union on May 20, 1861, the young men of Cold Mountain enlist in the Confederate States Army. Among them is W.P. Inman, a carpenter who has fallen in love with Ada Monroe, the preacher's daughter who came from Charleston, South Carolina, to care for her father. Their courtship is interrupted by the war, but they share their first kiss the day Inman leaves for battle. Ada promises to wait for him.

Three years later, Inman fights in the Battle of the Crater and survives. He then comforts a dying acquaintance from Cold Mountain, while fellow soldier Stobrod Thewes plays a tune on his fiddle. Inman is later wounded in a skirmish, and as he lies in a hospital near death, a nurse reads him a letter from Ada, who pleads for Inman to come home to her. Inman recovers and deserts. Embarking on a long trek back to Cold Mountain, he encounters a corrupt preacher Veasey and stops him from drowning his impregnated slave. Exiled from his parish, Veasey joins Inman on his journey. They meet a young man, Junior, and join him and his family for dinner. Junior betrays the duo to the Confederate Home Guard, who take Inman and Veasey away along with other deserters. Veasey and the group are killed in a skirmish with Union cavalry; Inman is left for dead. An elderly hermit finds Inman and nurses him back to health. Inman meets a grieving young widow Sara and her infant child Ethan and stays the night at her cabin. The next morning, three Union soldiers arrive, demanding food. They hold Ethan hostage and try to rape Sara, which forces Inman and Sara to kill them.

Back in Cold Mountain, Ada's father has died. With no money and little means to run the family farm in Black Cove, she survives on the kindness of her neighbors, particularly Esco and Sally Swanger, who eventually send for Ruby Thewes, an experienced farmer (and Stobrod's daughter), to help. Together they bring Black Cove to working order and become close friends. Ada continues to write letters to Inman, hoping they will reunite and renew their romance. Ada has several tense encounters with Captain Teague, the leader of the local Home Guard who covets Ada and her property. His grandfather once owned much of Cold Mountain. One day, Teague and his men kill Esco. They torture Sally to coax her deserter sons out of hiding and kill them as well. Ada and Ruby rescue Sally, who is traumatized and rendered mute. The women celebrate Christmas with Stobrod, who has come to Cold Mountain with fellow deserters and musicians Pangle and Georgia.

While camping in the woods one night, Stobrod and Pangle are cornered by Teague and the Guard while Georgia secretly watches. Pangle inadvertently reveals they are deserters, and the Guard shoots Pangle and Stobrod. Georgia escapes and informs Ruby and Ada, who find Pangle dead and Stobrod badly wounded. The women and Stobrod take shelter in an abandoned Cherokee camp. Ada hunts for food and is reunited with Inman, who has finally returned to Cold Mountain. They return to the camp and spend the night consummating their love. Heading home, Ada and Ruby are surrounded by Teague and his men, who had captured and tortured Georgia to learn their whereabouts. Inman arrives, and a gunfight occurs, resulting in Teague and most of his posse dying. Inman chases Bosie, Teague's lieutenant. They exchange fast draws; Bosie is killed, and Inman is mortally wounded. Ada finds and comforts Inman, who dies in her arms.

Years later, it is revealed that Ada's night with Inman produced a daughter, Grace Inman, and that Ruby has married Georgia and borne two children. With Stobrod and Sally, the family celebrates Easter together at Black Cove.

Cast

[edit]- Jude Law as William "W. P." Inman

- Nicole Kidman as Ada Monroe

- Renée Zellweger as Ruby Thewes

- Eileen Atkins as Maddy

- Kathy Baker as Sally Swanger

- James Gammon as Esco Swanger

- Brendan Gleeson as Stobrod Thewes

- Philip Seymour Hoffman as Reverend Solomon Veasey

- Natalie Portman as Sara

- Giovanni Ribisi as Junior

- Lucas Black as Oakley

- Donald Sutherland as Reverend Monroe

- Cillian Murphy as Bardolph

- Ethan Suplee as Pangle

- Jay Tavare as Swimmer

- Jack White as Georgia

- Ray Winstone as Teague

- Melora Walters as Lila

- Taryn Manning as Shyla

- Emily Deschanel as Mrs. Morgan

- Charlie Hunnam as Bosie

- Tom Aldredge as Blind Man

- James Rebhorn as Doctor

- Jena Malone as Ferry Girl

- Richard Brake as Nym

Production

[edit]In 1997, United Artists bought the rights to Cold Mountain for Anthony Minghella to write and direct, with Sydney Pollack as producer. MGM/United Artists and Miramax Films then announced a deal to produce eight films together, sharing the profits.[4]

As the script was developed, the scope of the film grew from a period love story with a budget of $40 million into an expensive epic. The budget grew to nearly $120 million, with Minghella having trouble finding American landscapes that could pass for 19th-century towns. Tom Cruise, at the time married to Nicole Kidman, wanted to play Inman, but the studio did not want to pay his $20 million demand. To get the budget down, production was moved to Romania, but three weeks before filming began in October 2002, MGM pulled out.[5] Executive producer Harvey Weinstein was going to cancel the shoot, but with Minghella already in pre-production Weinstein agreed to fund the $80 million project after receiving a $10 million tax break.[6]

Location

[edit]Cold Mountain, where the film is set, is a real mountain located within the Pisgah National Forest, Haywood County, North Carolina. However, the film was filmed mostly in Romania, with numerous scenes filmed in Virginia, South Carolina, and North Carolina. The film was one of an increasing number of Hollywood productions made in Eastern Europe as a result of lower costs in the region, and because, in this instance, Transylvania having less infrastructure like power cables and paved roads was less marked by modern life than the Appalachians.

Editing

[edit]The film marked a technological and industry turnaround in editing. Walter Murch edited Cold Mountain on Apple's sub-$1000 Final Cut Pro software "using several off-the-shelf PowerMac G4 computers".[3] This was a leap for such a big-budgeted film, where expensive Avid systems are usually the standard editing system. His efforts on the film were documented in the 2005 book Behind the Seen: How Walter Murch Edited Cold Mountain Using Apple's Final Cut Pro and What This Means for Cinema.[3]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]Cold Mountain grossed $95.6 million in the United States and Canada and $77.4 million in other territories, for a worldwide total of $173 million.[2] Executive producer Harvey Weinstein said the film would break-even if it grossed $135 million.[6] The film made $14.5 million in its opening weekend, finishing third at the box office. It made $11.7 million in its second weekend and $7.9 million in its third, finishing fourth both times.

Critical response

[edit]Cold Mountain opened to positive reviews from critics, with Law and Zellweger's performance receiving widespread critical acclaim. According to review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, 70% of 231 critics gave the film a positive review, with an average rating of 6.70/10. The site's critics consensus states: "The well-crafted Cold Mountain has an epic sweep and captures the horror and brutal hardship of war."[7] On Metacritic, the film was assigned a weighted average score of 73 out of 100 based on 41 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[8] Audiences surveyed by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of B+ on scale of A+ to F.[9]

Movie critic Roger Ebert gave the film three stars out of four, noting, "It evokes a backwater of the Civil War with rare beauty, and lights up with an assortment of colorful supporting characters."[10] Richard Corliss, film critic for Time, gave the film a positive review. He called it "A grand and poignant movie epic about what is lost in war and what's worth saving in life. It is also a rare blend of purity and maturity—the year's most rapturous love story."[11] In his movie guide, Leonard Maltin gave the film 3 1/2 stars out of 4, writing "Minghella's adaptation of the Charles Frazier best-seller captures both the grimness of battle and the starkness of life on the home front in the South," and concluded the film was "meticulously crafted" with "first-rate performances all around."[12]

Top ten lists

[edit]Cold Mountain was listed on many critics' top ten lists of 2003.[13]

- 1st – Stephen Hunter, The Washington Post

- 1st – Megan Lehmann, New York Post

- 2nd – Jonathan Foreman, New York Post

- 3rd – Ruthie Stein, San Francisco Chronicle

- 5th – Richard Corliss, TIME Magazine

- 5th – Peter Travers, Rolling Stone

- 7th – Lou Lumenick, New York Post

- 7th – Jonathan Rosenbaum, Chicago Reader

- 8th – Mike Clark, USA Today

- 8th – Wesley Morris, The Boston Globe

- Top 10 (listed alphabetically) – Kenneth Turan, Los Angeles Times

Historical accuracy

[edit]Several scholars of historical studies reviewed the film for its representation of North Carolina during the Civil War, especially the state's mountainous western region. Their justification is the effect popular media have on national and worldwide perceptions of Appalachian people, particularly southern Appalachians in this case. The opinions vary, but the consensus among them is the historical context of the movie is close to the scholarship.[14][15][16]

Scholars praised the film for its conformity to the historical scholarship in other subjects, with one saying "The final product should... provide so unflinching a portrayal of the bleak and unsettling realities of a far less familiar version of the Civil War, but one that would be all too recognizable to thousands of hardscrabble southern men and women who lived through it."

One scholar said, "Some of the best of the soundtrack was not composed for the movie but garnered from the body of time-tested and proven masterpieces of an earlier rural American culture." Such selections were not necessarily performed authentically in the film: the two Sacred Harp songs, although generally authentic to the period and region, contained vocal parts not yet written at that time.[17]

The beginning Battle of the Crater is depicted as happening in broad daylight but it began at 4:44 am with the detonation of the mine.

Soundtrack

[edit]Cold Mountain: Music from the Motion Picture shares producer T Bone Burnett with the soundtrack for O Brother, Where Art Thou?, a largely old-time and folk album with limited radio play that still enjoyed commercial success, and garnered a Grammy. As a result, comparisons were drawn between the two albums. Burnett brought in musician and scholar Tim Eriksen to teach the performers Sacred Harp singing, which features prominently in the sountrack.[18]

It features songs written by Jack White of The White Stripes (who also appeared in the film in the role of Georgia), Elvis Costello and Sting. Costello and Sting's contributions, "The Scarlet Tide" and "You Will Be My Ain True Love", were both nominated for the Academy Award for Best Original Song and featured vocals by bluegrass singer Alison Krauss. Gabriel Yared's Oscar-nominated score is represented by four tracks amounting to approximately fifteen minutes of music.

Awards

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Cold Mountain (2003)". bfi.org.uk. British Film Institute. Archived from the original on January 30, 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ a b c "Cold Mountain (2003)". Box Office Mojo. Internet Movie Database. Archived from the original on 2014-02-21. Retrieved 2010-10-18.

- ^ a b c Cellini, Joe. "Walter Murch: An Interview with the Editor of 'Cold Mountain'". Apple.com. Archived from the original on 2011-08-20. Retrieved 2023-12-30.

- ^ Bates, James (7 July 1999). "Miramax, MGM in Deal to Make Movies". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2024-11-26.

- ^ "MGM gets 'Cold' feet". Variety.com. 2002-10-27. Retrieved 2024-06-28.

- ^ a b "The Civil War Is a Risky Business: Miramax's Bet on 'Cold Mountain'". The New York Times. December 17, 2003. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ^ "Cold Mountain". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on 2017-11-27. Retrieved January 5, 2023.

- ^ "Cold Mountain". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on 2023-02-27. Retrieved 2010-10-09.

- ^ "COLD MOUNTAIN (2003) B+". CinemaScore. Archived from the original on 2018-12-20.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (December 24, 2003). "Cold Mountain Movie Review & Film Summary (2003)". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on April 19, 2015. Retrieved September 15, 2019.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (December 14, 2003). "O Lover, Where Art Thou?". Time. Archived from the original on April 14, 2019. Retrieved September 15, 2019.

- ^ Maltin, Leonard (2012). 2013 Movie Guide. Penguin Books. p. 268. ISBN 978-0-451-23774-3.

- ^ "Movie Reviews, Articles, Trailers, and more". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 12 February 2010.

- ^ Arnold, Edwin T.; Blethen, Tyler; Tipton Cortner, Amy; et al. (Spring–Summer 2004). "APPALJ Roundtable Discussion: Cold Mountain, the Film". Appalachian Journal: 316–353. JSTOR 40934797. Archived from the original on 2016-08-18.

- ^ Crawford, Martin (Winter–Spring 2003). "Cold Mountain Fictions: Appalachian Half-Truths. Review of Cold Mountain by Charles Frazier". Appalachian Journal: 182–195.

- ^ Inscoe, John C. (December 2004). "Cold Mountain Review". The Journal of American History: 1127–1129. doi:10.2307/3663028. JSTOR 3663028.

- ^ "Cooper v. James". mcir.usc.edu. Music Copyright Infringement Resource, Gould School of Law, University of Southern California. Archived from the original on 2014-05-19. Retrieved 2014-05-23.

At the time of the Civil War these songs, in the only available edition of the Sacred Harp, had only one verse apiece, and neither contained an alto part.

- ^ Hukill, Traci (April 22, 2009). "Northern Star". Santa Cruz Weekly.

Bibliography

[edit]- Tibbetts, John C., and James M. Welsh, eds. The Encyclopedia of Novels Into Film (2nd ed. 2005) pp. 63–66.

External links

[edit]- 2003 films

- 2000s American films

- 2000s English-language films

- 2000s romance films

- 2000s war films

- American Civil War films based on actual events

- BAFTA winners (films)

- English-language Italian films

- English-language Romanian films

- Films about deserters

- Films based on American novels

- Films based on the Odyssey

- Films directed by Anthony Minghella

- Films featuring a Best Supporting Actress Academy Award–winning performance

- Films featuring a Best Supporting Actress Golden Globe–winning performance

- Films produced by Sydney Pollack

- Films scored by Gabriel Yared

- Films set in 1864

- Films set in North Carolina

- Films set in Appalachia

- Films shot in North Carolina

- Films shot in Romania

- Films shot in South Carolina

- Films shot in Virginia

- Miramax films

- War romance films

- American Civil War films

- English-language romance films

- English-language war films

- Cattleya films