William C. Gorgas

William Crawford Gorgas | |

|---|---|

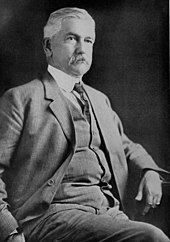

Gorgas during World War I | |

| Born | October 3, 1854 Toulminville, Alabama, US |

| Died | July 3, 1920 (aged 65) London, England |

| Place of burial | |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1880–1918 |

| Rank | |

| Commands | Surgeon General of the US Army |

| Awards | Distinguished Service Medal Public Welfare Medal (1914) |

| Relations | Josiah Gorgas (father) Amelia Gayle Gorgas (mother) John Gayle (grandfather) |

William Crawford Gorgas KCMG (October 3, 1854 – July 3, 1920) was a United States Army physician and 22nd Surgeon General of the U.S. Army (1914–1918). He is best known for his work in Florida, Havana and at the Panama Canal in abating the transmission of yellow fever and malaria by controlling the mosquitoes that carry these diseases, for which he used the discoveries made by the Cuban doctor Carlos J. Finlay. At first, Finlay's strategy was greeted with considerable skepticism and opposition to such hygiene measures. However, the measures Gorgas put into practice as the head of the Panama Canal Zone Sanitation Commission saved thousands of lives and contributed to the success of the canal's construction.

He was a Georgist and argued that adopting Henry George's popular 'Single Tax' would be a way to bring about sanitary living conditions, especially for the poor.[1]

Early life and education

[edit]Born in Toulminville, Alabama, Gorgas was the first of six children of Josiah Gorgas and Amelia Gayle Gorgas. His maternal grandparents were Governor John Gayle and Sarah Ann Haynsworth Gayle, the diarist.[2]

After studying at The University of the South and Bellevue Hospital Medical College, Dr. Gorgas was appointed to the US Army Medical Corps in June 1880.[3]

Military career

[edit]

He was assigned to three posts—Fort Clark, Fort Duncan, and Fort Brown—in Texas. He was sent to Fort Brown (1882–84) to take control of an epidemic of yellow fever. One of his patients was Marie Cook Doughty, who nearly died from the disease. In the course of caring for her, he contracted the disease himself. They both recovered together, and during the time of convalescence, fell in love, soon thereafter getting married.[4][5][3] Having recovered from the disease, they both now had lifetime immunity and consequently were assigned to other yellow fever outbreaks.[4]

In 1898, after the end of the Spanish–American War, Gorgas was appointed Chief Sanitary Officer in Havana, where he and Robert Ernest Noble worked to eradicate yellow fever and malaria.[6] Gorgas capitalized on the momentous work of another Army doctor, Major Walter Reed, who had built much of his work on the insights of Cuban doctor, Carlos Finlay, to prove the mosquito transmission of yellow fever. Through his efforts draining both the Aedes aegypti mosquito vector breeding ponds and quarantining of yellow fever patients in screened service rooms, cases in Havana plunged from 784 to zero within a year.[7]

As chief sanitary officer on the canal project, Gorgas implemented far-reaching sanitary programs, including the draining of ponds and swamps, fumigation, use of mosquito netting, and construction of public water systems. These measures were instrumental in permitting the construction of the Panama Canal, as they significantly prevented illness due to yellow fever and malaria (which had also been shown to be transmitted by mosquitoes in 1898) among the thousands of workers involved in the building project.[8]

Gorgas served as president of the American Medical Association in 1909–10. He was appointed as Surgeon General of the Army in 1914. That same year, Gorgas and George Washington Goethals were awarded the inaugural Public Welfare Medal from the National Academy of Sciences.

Gorgas retired from the Army in 1918, having reached the mandatory retirement age of 64.[9]

Personal life

[edit]He was married to Marie Cook Doughty (1862–1929) of Cincinnati.[3] He is buried with her at Arlington National Cemetery, in Arlington, Virginia.[10]

Death and legacy

[edit]- He received an honorary knighthood (KCMG) from King George V at the Queen Alexandra Military Hospital in the United Kingdom shortly before his death there on July 3, 1920.[11] He was given a special funeral in St. Paul's Cathedral.[12]

- Gorgas' name features on the Frieze of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. Twenty-three names of public health and tropical medicine pioneers were chosen to feature on the School building in Keppel Street when it was constructed in 1926.[13]

- Gorgas, Alabama was named after him.[14]

Awards and Honors

[edit]Military Awards

[edit]- Distinguished Service Medal (U.S. Army)[15]

- Spanish Campaign Medal

- Army of Cuban Occupation Medal

- Victory Medal

Other honors

[edit]- Elected member of the American Philosophical Society[16]

- Public Welfare Medal – National Academy of Sciences[17]

- Elected member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences[18]

- Honorary Knight Commander of Michael and George (KCMG) (United Kingdom)

Legacy

[edit]

- The Gorgas Memorial Institute of Tropical and Preventive Medicine, Incorporated (GMITP), which operated the Gorgas Laboratories in Panama, was founded in 1921 and was named after Dr. Gorgas. With the loss of congressional funding in 1990, the GMITP was closed. The institute was moved to the University of Alabama in 1992 and carries on the tradition of research, service and training in tropical medicine. The Gorgas Course in Clinical Tropical Medicine is sponsored by the University of Alabama School of Medicine in conjunction with Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia in Lima, Peru.

- Gorgas Hospital was a U.S. Army hospital in Panama, previously known as Ancon Hospital and named for Dr. Gorgas in 1928. Now held and operated by Panama, it is home to the Instituto Oncologico Nacional, Panama's Ministry of Health and its Supreme Court.

- In 1947 the Gorgas Science Foundation was founded at Texas Southmost College (on the site of the former Fort Brown). The foundation supports conservation and ecological science research projects worldwide.

- The Gorgas Medal is awarded by the Association of Military Surgeons of the United States (AMSUS)

- In 1953 William C. Gorgas was inducted into the Alabama Hall of Fame.

- Amelia Gayle Gorgas Library and Gorgas' parents' final home, the Gorgas House, located on the campus of The University of Alabama, are named in honor of the Gorgas family.[19]

- Texas Southmost College has a Gorgas Hall named in his honor. The college's campus is located on the grounds of the former Fort Brown.

- The Alabama Power Company renamed its Warrior Reserve Steam Plant on the Black Warrior River near Parrish in honor of Gorgas in the 1920s. Gorgas had testified on behalf of the utility during the previous decade in lawsuits over mosquito-borne illnesses in the vicinity of its Lay Dam hydroelectric reservoir.[20] The coal-fired steam plant was closed in April 2019.

- The German commercial passenger ship-cargo ship SS Prinz Sigismund, after being seized by the United States after it entered World War I on the side of the Allies, had a long American career under the name General W. C. Gorgas (named for Dr. Gorgas). It was owned by the Panama Railroad Company and used for commercial service as SS General W. C. Gorgas from 1917 to 1919 and from 1919 to 1941, it was used as the U.S. Navy troop transport USS General W. C. Gorgas in 1919 after World War I, and as the U.S. Army Transport USAT General W. C. Gorgas from 1941 to 1945 during World War II.

- Gorgas's Rice Rat (Oryzomys gorgasi) is a South American rodent named after Gorgas in 1971.

- The Latin University of Panama (Universidad Latina de Panama) named their health sciences faculty in Gorgas's honor (Facultad de ciencias de la salud Dr. William C. Gorgas).

- There is a Gorgas Avenue in the Presidio in San Francisco, California.[21]

- Gorgas Hall at Sewanee - The University of the South is named in his honor and was ranked the worst dorm at Sewanee in 2022 by College Jaguar [2]

- In 1984 the "Major General William C. Gorgas Clinic" was dedicated as part of the Mobile County Health Department, located at 251 North Bayou Street, Mobile, AL [3]

- Gorgas's papers are held at the National Library of Medicine in Bethesda, Maryland.[22]

- There is a Gorgas Road on Fort Myer, Virginia[23]

See also

[edit]- Health measures during the construction of the Panama Canal

- Postage stamps and postal history of the Canal Zone

- Sanitation

- Vector control

- Tropical disease

- Miasma theory of disease

References

[edit]- ^ The Great Adventure, Volume 4. Great Adventure League. 1920. Retrieved May 31, 2015.

- ^ Owen, Marie Bankhead, ed. (1927). Publications: Historical and patriotic series. Montgomery, Alabama: Birmingham Printing Company. p. 308. Retrieved December 5, 2023.

- ^ a b c Davis, Henry Blaine Jr. (1998). Generals in Khaki. Pentland Press, Inc. pp. 151–152. ISBN 1571970886. OCLC 40298151.

- ^ a b McCullough 1977, p. 412.

- ^ "Mrs. W. C. Gorgas, General's Widow, Dies". New York Times. November 10, 1929. Retrieved November 13, 2010.

- ^ "William Gorgas, 1854–1920". Harvard University. Retrieved September 5, 2008.

- ^ McCullough 1977, p. 415.

- ^ "Contagion, Tropical Diseases and the Construction of the Panama Canal, 1904–1914". Harvard University. Retrieved September 6, 2008.

- ^ "Public Welfare Award". National Academy of Sciences. Retrieved February 14, 2011.

- ^ "Burial Detail: Gorgas, William C. (Section 2, Grave 1039)". ANC Explorer. Arlington National Cemetery. (Official website).

- ^ "Famous Surgeon is Dead". Associated Press. Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved November 13, 2010.

Maj. Gen. William C. Gorgas, former Surgeon-General of the United States Army, died at an early hour this morning. Gen. Gorgas's death was very peaceful. He was unconscious most of the time for the last few day

- ^ After his death, Gorgas's ongoing work (through the Rockefeller Foundation) in eliminating yellow fever in Mexico and Central America was carried on by retired Brigadier General Theodore C. Lyster.

- ^ "Behind the Frieze". Archived from the original on February 22, 2017. Retrieved February 21, 2017.

- ^ Foscue, Virginia O. (1989). Place Names in Alabama. University of Alabama Press. p. 64. ISBN 081730410X. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- ^ "Valor awards for William Crawford Gorgas". Military Times.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved November 15, 2023.

- ^ "William C. Gorgas". www.nasonline.org. Retrieved November 15, 2023.

- ^ "William Crawford Gorgas". American Academy of Arts & Sciences. February 9, 2023. Retrieved November 15, 2023.

- ^ "The University of Alabama". Ua.edu. Retrieved March 9, 2022.

- ^ Atkins, Leah Rawls (2006). 'Developed for the Service of Alabama': The Centennial History of the Alabama Power Company. Birmingham, Alabama: Alabama Power Company.

- ^ "Maps - Presidio of San Francisco (U.S. National Park Service)". Nps.gov. Retrieved March 9, 2022.

- ^ "William Crawford Gorgas Papers 1890–1918". National Library of Medicine.

- ^ [1] [dead link]

- From the brochure "150 Year Celebration of the U.S. Marine Hospital/Mobile County Health Department" – December 15, 1993 – Bernard H. Eichold, II M.D., Dr. P.H., Health Officer

Further reading

[edit]

- Ashburn, P.M., History of the Medical Department of the U.S. Army, 1929.

- Gibson, John M., Physician to the World: The Life of General William C. Gorgas, Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 1950.

- Gorgas, Marie and Burton J. Hendrick, William Crawford Gorgas: His Life and Work, New York: Doubleday, 1924.

- McCullough, David (1977). The Path between the Seas: the Creation of the Panama Canal 1870-1914. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0671244094.

- Mellander, Gustavo A., Mellander, Nelly, Charles Edward Magoon: The Panama Years. Río Piedras, Puerto Rico: Editorial Plaza Mayor. ISBN 1-56328-155-4. OCLC 42970390. (1999)

- Mellander, Gustavo A., The United States in Panamanian Politics: The Intriguing Formative Years." Danville, Ill.: Interstate Publishers. OCLC 138568 (1971)

- Phalen, James M., "Chiefs of the Medical Department, U.S. Army 1775–1940, Biographical Sketches," Army Medical Bulletin, No. 52, April 1940, pp. 88–93.

- Wilson, Owen (July 1908). "The Conquest Of The Tropics: How Col. Gorgas's Sanitary Work At Panam Has Proved The Possibility of Beautiful Tropical Residence". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. XVI: 10432–10445. Retrieved July 10, 2009.

- Endorsements, Resolutions and other Data in Behalf of the Nomination of Dr. William Crawford Gorgas for Election to the New York Hall of Fame for Great Americans, 2 vols., Birmingham: Gorgas Hall of Fame Committee, 1950.

Obituaries:

- "William Crawford Gorgas". The Scientific Monthly. 11 (2): 187–190. 1920. Bibcode:1920SciMo..11..187.

- Ireland, M.W. (1920). "General William C. Gorgas". Science. 52 (1333): 54. Bibcode:1920Sci....52...53I. doi:10.1126/science.52.1333.53. PMID 17736545.

- Martin, Franklin H. (1923). "William Crawford Gorgas". Surgery, Gynecology and Obstetrics. October: 546–558.

- Noble, R.E. (1921). "William Crawford Gorgas". Am J Public Health. 11 (3): 250–256. doi:10.2105/ajph.11.3.250. PMC 1353777. PMID 18010462.

- Siler, J.F. (1922). "Major-General William Crawford Gorgas". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine. 1 (2): 161–171. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.1922.s1-2.161.

External links

[edit]- Video: William Gorgas Biography on Health.mil – The Military Health System provides a look at the life and work of William Gorgas.

- The Gorgas Memorial Institute, University of Alabama

- Gorgas Memorial Library, at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research

- Alabama Hall of Fame Bio

- The Gorgas TB Initiative

- Gorgas Science Foundation Website

- Mobile County Health Department – Maj. Gen. William C. Gorgas Clinic

- William Crawford Gorgas papers, W.S. Hoole Special Collections Library, The University of Alabama

- "William Crawford Gorgas". at ArlingtonCemetery.net. January 22, 2023. (Unofficial website).

- 1854 births

- 1920 deaths

- Surgeons General of the United States Army

- Panama Canal

- Malariologists

- Walter Reed

- Military personnel from Mobile, Alabama

- Sewanee: The University of the South alumni

- United States Army generals of World War I

- United States Army generals

- Burials at Arlington National Cemetery

- United States Army Medical Corps officers

- Recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (US Army)

- Honorary Knights Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George

- Physicians from Alabama

- Hall of Fame for Great Americans inductees

- American tropical physicians

- Georgists

- Presidents of the American Medical Association

- Members of the American Philosophical Society

- 19th-century United States Army personnel