Bupropion

| |

1 : 1 mixture (racemate) | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /bjuːˈproʊpiɒn/ bew-PROH-pee-on am-fa-BEW-teh-moan |

| Trade names | Wellbutrin, Zyban, others |

| Other names | Amfebutamone; 3-Chloro-N-tert-butyl-β-keto-α-methylphenethylamine; 3-Chloro-N-tert-butyl-β-ketoamphetamine; 3-Chloro-N-tert-butylcathinone |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a695033 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral (swallowed by mouth)[2][3] |

| Drug class | NDRI antidepressants |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Unknown[2] |

| Protein binding | Bupropion: 84%[14] Hydroxybupropion: 77%[14] Threohydrobupropion: 42%[14] |

| Metabolism | Liver, intestines (CYP2B6, others)[2] |

| Metabolites | • Hydroxybupropion • Threohydrobupropion • Erythrohydrobupropion • Others |

| Elimination half-life | Bupropion: 0.5–1.04 h[15][2] Hydroxybupropion: 20 h[2] Threohydrobupropion: 37 h[2] Erythrohydrobupropion: 33 h[2] |

| Excretion | Urine: 87% (0.5% unchanged)[2] Feces: 10%[2] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C13H18ClNO |

| Molar mass | 239.74 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Bupropion, formerly called amfebutamone,[16] and sold under the brand name Wellbutrin among others, is an atypical antidepressant primarily used to treat major depressive disorder, seasonal affective disorder and to support smoking cessation.[17][18] It is also popular as an add-on medication in the cases of "incomplete response" to the first-line selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressant.[18][19] Bupropion has several features that distinguish it from other antidepressants: it does not usually cause sexual dysfunction,[18] it is not associated with weight gain[18] and sleepiness,[20] and it is more effective than SSRIs at improving symptoms of hypersomnia and fatigue.[21] Bupropion, particularly the immediate-release formulation, carries a higher risk of seizure than many other antidepressants, hence caution is recommended in patients with a history of seizure disorder.[22] The medication is taken by mouth.[2][3]

Common adverse effects of bupropion with the greatest difference from placebo are dry mouth, nausea, constipation, insomnia, anxiety, tremor, and excessive sweating.[10][11] Raised blood pressure is notable.[23] Rare but serious side effects include seizures,[10][11] liver toxicity,[24] psychosis,[25] and risk of overdose.[26] Bupropion use during pregnancy may be associated with increased likelihood of congenital heart defects.[27]

Bupropion acts as a norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitor (NDRI) and a nicotinic receptor antagonist.[2] However, its effects on dopamine are weak and clinical significance is contentious.[28][29][30][31][32] Chemically, bupropion is an aminoketone that belongs to the class of substituted cathinones and more generally that of substituted amphetamines and substituted phenethylamines.[33][34]

Bupropion was invented by Nariman Mehta, who worked at Burroughs Wellcome, in 1969.[35] It was first approved for medical use in the United States in 1985.[36] Bupropion was originally called by the generic name amfebutamone, before being renamed in 2000.[16] In 2022, it was the 21st most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 25 million prescriptions.[37][38] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[39]In 2022, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the combination dextromethorphan/bupropion to serve as a rapid-acting antidepressant in patients with major depressive disorder.[40]

Medical uses

[edit]

Depression

[edit]The evidence overall supports the effectiveness of bupropion over placebo for the treatment of depression.[41][18][42] Some peer-reviewed studies suggest the quality of evidence is low.[42][18] Some meta-analyses report that bupropion has an at-most small effect size for depression.[43][44][42][45] One meta-analysis reported a large effect size.[18] However, there were methodological limitations with this meta-analysis, including using a subset of only five trials for the effect size calculation, substantial variability in effect sizes between the selected trials—which led the authors to state that their findings in this area should be interpreted with "extreme caution"—and general lack of inclusion of unpublished trials in the meta-analysis.[18] Unpublished trials are more likely to be negative in findings,[46][47] and other meta-analyses have included unpublished trials.[43][44][42][45] Evidence suggests that the effectiveness of bupropion for depression is similar to that of other antidepressants.[43][44][18]

Over the autumn and winter months, bupropion prevents the development of depression in those who have recurring seasonal affective disorder: 15% of participants on bupropion experienced a major depressive episode vs. 27% of those on placebo.[48] Bupropion also improves depression in bipolar disorder, with the efficacy and risk of an affective switch being similar to other antidepressants.[49]

Bupropion has several features that distinguish it from other antidepressants: for instance, unlike the majority of antidepressants, it does not usually cause sexual dysfunction, and the occurrence of sexual side effects is not different from placebo.[18][50] Bupropion treatment is not associated with weight gain; on the contrary, the majority of studies observed significant weight loss in bupropion-treated participants.[18] Bupropion treatment also is not associated with the sleepiness that may be produced by other antidepressants.[20] Bupropion is more effective than selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) at improving symptoms of hypersomnia and fatigue in depressed patients.[21] Bupropion is effective in the treatment of anxious depression and, contrary to common belief, does not exacerbate anxiety in this context.[51][52] The effectiveness of bupropion for anxious depression is equivalent to that of SSRIs in the case of depression with low or moderate anxiety, whereas SSRIs show a modest effectiveness advantage in terms of response rates for depression with high anxiety.[51]

The addition of bupropion to a prescribed SSRI is a common strategy when people do not respond to the SSRI,[19] and it is supported by clinical trials;[18] however, it appears to be inferior to the addition of atypical antipsychotic aripiprazole.[53][further explanation needed]

Smoking cessation

[edit]Prescribed as an aid for smoking cessation, bupropion reduces the severity of craving for nicotine and withdrawal symptoms[54][55][56] such as depressed mood, irritability, difficulty concentrating, and increased appetite.[57] Initially, bupropion slows the weight gain that often occurs in the first weeks after quitting smoking. With time, however, this effect becomes negligible.[57]

The bupropion treatment course lasts for seven to twelve weeks, with the patient halting the use of tobacco about ten days into the course.[57][10] After the course, the effectiveness of bupropion for maintaining abstinence from smoking declines over time, from 37% of tobacco abstinence at 3 months to 20% at one year.[58] It is unclear whether extending bupropion treatment helps to prevent relapse of smoking.[59]

Overall, six months after the therapy, bupropion increases the likelihood of quitting smoking by approximately 1.6-fold as compared to placebo. In this respect, bupropion is as effective as nicotine replacement therapy but inferior to varenicline. Combining bupropion and nicotine replacement therapy does not improve the quitting rate.[60]

In children and adolescents, the use of bupropion for smoking cessation does not appear to offer any significant benefits.[61] The evidence for its use to aid smoking cessation in pregnant women is insufficient.[62]

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

[edit]In the United States, the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is not an approved indication of bupropion, and it is not mentioned in the 2019 guideline on ADHD treatment from the American Academy of Pediatrics.[63] Systematic reviews of bupropion for the treatment of ADHD in both adults and children note that bupropion may be effective for ADHD but warn that this conclusion has to be interpreted with caution, because clinical trials were of low quality due to small sizes and risk of bias.[30][64][65][66] Similarly to atomoxetine, bupropion has a delayed onset of action for ADHD, and several weeks of treatment are required for therapeutic effects.[30][67] This is in contrast to stimulants, such as amphetamine and methylphenidate, which have an immediate onset of effect in the condition.[67]

Sexual dysfunction

[edit]Bupropion is less likely than other antidepressants to cause sexual dysfunction.[68] A range of studies indicate that bupropion not only produces fewer sexual side effects than other antidepressants but can actually help to alleviate sexual dysfunction[69] including sexual dysfunction induced by SSRI antidepressants.[70] There have also been small studies suggesting that bupropion or a bupropion/trazodone combination may improve some measures of sexual function in women who have hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) and are not depressed.[71] According to an expert consensus recommendation from the International Society for the Study of Women's Sexual Health, bupropion can be considered as an off-label treatment for HSDD despite limited safety and efficacy data.[72] Likewise, a 2022 systematic review and meta-analysis of bupropion for sexual desire disorder in women reported that although data were limited, bupropion appeared to be dose-dependently effective for the condition.[73]

Weight loss

[edit]Bupropion, when used for treating long-term weight gain over six to twelve months, results in an average weight loss of 2.7 kilograms (6.0 lb) over placebo.[74] This is not much different from the weight loss produced by several other weight-loss medications such as sibutramine or orlistat.[74] The combination drug naltrexone/bupropion has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of obesity.[75][76]

Other uses

[edit]Bupropion is not effective in the treatment of cocaine dependence,[77] but it is showing promise in reducing drug use in treating amphetamine-type stimulant use and cravings.[78][79] Based on studies indicating that bupropion lowers the level of the inflammatory mediator TNF-alpha, there have been suggestions that it might be useful in treating inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis, and other autoimmune conditions, but very little clinical evidence is available.[80][81][82] Bupropion is not effective in treating chronic low back pain.[83] The drug may be useful in the treatment of excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) and narcolepsy.[84][85][86][87]

Bupropion has been used to treat disorders of diminished motivation, like apathy, abulia, and akinetic mutism.[88][89] Accordingly, the drug has been found to increase effort expenditure and improve motivational deficits in animal models.[88] However, only limited benefits of bupropion in the treatment of apathy have been observed in clinical trials in various conditions.[88]

Bupropion has been used in the treatment of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS).[90][91]

Available forms

[edit]Bupropion is available as an oral tablet in several different formulations.[10][11] It is mainly formulated as the hydrochloride salt[10][11] but also as the hydrobromide salt.[12] In addition to single-drug formulations, bupropion is formulated in combinations including naltrexone/bupropion (Contrave) for obesity and dextromethorphan/bupropion (Auvelity) for depression.[92][93]

Contraindications

[edit]The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) prescription label advises that bupropion should not be prescribed to individuals with epilepsy or other conditions that lower the seizure threshold, such as anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, or benzodiazepine or alcohol withdrawal. It should be avoided in individuals who are taking monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). The label recommends that caution should be exercised when treating people with liver damage, severe kidney disease, and severe hypertension, and in children, adolescents, and young adults due to the increased risk of suicidal ideation.[10]

Side effects

[edit]The common adverse effects of bupropion with the greatest difference from placebo are dry mouth, nausea, constipation, insomnia, anxiety, tremor, and excessive sweating.[10][11] Bupropion has the highest incidence of insomnia of all second-generation antidepressants, apart from desvenlafaxine.[94] It is also associated with about 20% increased risk of headache.[95]

Bupropion raises blood pressure in some people. One study showed an average rise of 6 mm Hg in systolic blood pressure in 10% of patients.[23] The prescribing information notes that hypertension, sometimes severe, is observed in some people taking bupropion, both with and without pre-existing hypertension.[10][11] The safety of bupropion in people with cardiovascular conditions and its general cardiovascular safety profile remains unclear due to the lack of data.[96][97]

Seizure is a rare but serious adverse effect of bupropion. It is strongly dose-dependent: for the immediate release preparation, the seizure incidence is 0.4% at the dose 300–450 mg per day; the incidence climbs almost ten-fold for the higher than recommended dose of 600 mg.[10][11] For comparison, the incidence of unprovoked seizure in the general population is 0.07–0.09%, and the risk of seizure for a variety of other antidepressants is generally 0–0.5% at the recommended doses.[98]

Cases of liver toxicity leading to death or liver transplantation have been reported for bupropion. It is considered to be one of several antidepressants with a greater risk of hepatotoxicity.[24]

The prescribing information warns about bupropion triggering an angle-closure glaucoma attack.[10] On the other hand, bupropion may decrease the risk of development of open angle glaucoma.[99]

Bupropion use by mothers in the first trimester of pregnancy is associated with a 23% increase in the odds of congenital heart defects in their children.[27]

Bupropion has rarely been associated with instances of Stevens–Johnson syndrome.[100][101]

Bupropion has not been associated with QT prolongation at therapeutic doses but has been associated with QT prolongation in overdose.[102][103][104]

Psychiatric

[edit]The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requires all antidepressants, including bupropion, to carry a boxed warning stating that antidepressants may increase the risk of suicide in people younger than 25. This warning is based on a statistical analysis conducted by the FDA which found a 2-fold increase in suicidal thought and behavior in children and adolescents, and a 1.5-fold increase in the 18–24 age group.[105] For this analysis the FDA combined the results of 295 trials of 11 antidepressants to obtain statistically significant results. Considered in isolation, bupropion was not statistically different from placebo.[105]

Bupropion prescribed for smoking cessation results in a 25% increase in the risk of psychiatric side effects, in particular, anxiety (about 40% increase) and insomnia (about 80% increase). The evidence is insufficient to determine whether bupropion is associated with suicides or suicidal behavior.[55]

In rare cases, bupropion-induced psychosis may develop. It is associated with higher doses of bupropion; many cases described are at higher than recommended doses. Concurrent antipsychotic medication appears to be protective.[25] In most cases the psychotic symptoms are eliminated by reducing the dose, ceasing treatment or adding antipsychotic medication.[10][25]

Although studies are lacking, a handful of case reports suggest that abrupt discontinuation of bupropion may cause antidepressant discontinuation syndrome.[106]

Overdose

[edit]Bupropion is considered moderately dangerous in overdose.[107][108] According to an analysis of US National Poison Data System, adjusted for the number of prescriptions, bupropion and venlafaxine are the two new generation antidepressants (that is excluding tricyclic antidepressants) that result in the highest mortality and morbidity.[26] For significant overdoses, seizures have been reported in about a third of all cases; other serious effects include hallucinations, loss of consciousness, and abnormal heart rhythms. When bupropion was one of several kinds of pills taken in an overdose, fever, muscle rigidity, muscle damage, hypertension or hypotension, stupor, coma, and respiratory failure have been reported. While most people recover, some people have died, having had multiple uncontrolled seizures and myocardial infarction.[10]

Interactions

[edit]Since bupropion is metabolized to hydroxybupropion by the enzyme CYP2B6, drug interactions with CYP2B6 inhibitors are possible: this includes such medications as paroxetine, sertraline, norfluoxetine (active metabolite of fluoxetine), diazepam, clopidogrel, and orphenadrine. The expected result is an increase of bupropion and a decrease in hydroxybupropion blood concentration. The reverse effect (decrease of bupropion and increase of hydroxybupropion) can be expected with CYP2B6 inducers such as carbamazepine, clotrimazole, rifampicin, ritonavir, St John's wort, and phenobarbital.[109] Indeed, carbamazepine decreases exposure to bupropion by 90% and increases exposure to hydroxybupropion by 94%.[110] Ritonavir, lopinavir/ritonavir, and efavirenz have been shown to decrease levels of bupropion and/or its metabolites.[111] Ticlopidine and clopidogrel, both potent CYP2B6 inhibitors, have been found to considerably increase bupropion levels as well as decrease levels of its metabolite hydroxybupropion.[111]

Bupropion and its metabolites are inhibitors of CYP2D6, with hydroxybupropion responsible for most of the inhibition. Additionally, bupropion and its metabolites may decrease the expression of CYP2D6 in the liver. The end effect is a significant slowing of the clearance of other drugs metabolized by this enzyme.[2] For instance, bupropion has been found to increase area-under-the-curve of desipramine, a CYP2D6 substrate, by 5-fold.[111] Bupropion has also been found to increase levels of atomoxetine by 5.1-fold, while decreasing the exposure to its main metabolite by 1.5-fold.[112] As another example, the ratio of dextromethorphan (a drug that is mainly metabolized by CYP2D6) to its major metabolite dextrorphan increased approximately 35-fold when it was administered to people being treated with 300 mg/day bupropion.[109] When people on bupropion are given MDMA, about 30% increase of exposure to both drugs is observed, with enhanced mood but decreased heart rate effects of MDMA.[113][114] Interactions with other CYP2D6 substrates, such as metoprolol, imipramine, nortriptyline,[114] venlafaxine,[109] and nebivolol[2] have also been reported. However, in a notable exception, bupropion does not seem to affect the concentrations of CYP2D6 substrates fluoxetine and paroxetine.[109][115]

Bupropion lowers the seizure threshold, and therefore can potentially interact with other medications that also lower it, such as antipsychotics, tricyclic antidepressants, theophylline, and systemic corticosteroids.[10] The prescribing information recommends minimizing the use of alcohol, since in rare cases bupropion reduces alcohol tolerance.[10]

Caution should be observed when combining bupropion with a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI), as it may result in hypertensive crisis.[116]

Pharmacology

[edit]Pharmacodynamics

[edit]| Site | Value (nM) | Type | Species | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAT | 173–1,800 372–2,780 330–2,900 550–2,170 |

Ki Ki IC50 IC50 |

Human Rat Human Rat | |

| NET | 3,640–52,000 940–1,900 443–3,240 1,400–1,900 |

Ki Ki IC50 IC50 |

Human Rat Human Rat | |

| SERT | 9,100–>100,000 1,000–>10,000 47,000–>100,000 15,600 |

Ki Ki IC50 IC50 |

Human Rat Human Rat | |

| α1/1A-AdR | 4,200–16,000 | Ki | Human | |

| α2/2A-AdR | >10,000–81,000 | Ki | Human | |

| H1 | 6,600–>10,000 | Ki | Human | |

| σ1 | 580–2,100 | IC50 | Rodent | |

| α1-nACh | 7,600–28,000 | IC50 | Human | |

| α3β2-nACh | 1,000 | IC50 | Human | |

| α3β4-nACh | 1,800 | IC50 | Human | |

| α4β2-nACh | 12,000 | IC50 | Human | |

| α4β4-nACh | 12,000–14,000 | IC50 | Human | |

| α7-nACh | 7,900–50,000 | IC50 | Human | |

| α/β/δ/γ-nACh | 7,900 | IC50 | Human | |

| hERG | 34,000–69,000 | IC50 | Human | |

| Notes: (1) Values are in nanomolar (nM) units. The smaller the value, the more avidly the drug binds to or affects the site. (2) Affinities (Ki) were >10,000 nM at a variety of other sites (5-HT1, 5-HT2, β-adrenergic, D1, D2, mACh, nACh, GABAA). More: [120][121][122][123][124][125] | ||||

The mechanism of action of bupropion in the treatment of depression and for other indications is unclear.[2] However, it is thought to be related to the fact that bupropion is a norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitor (NDRI) and negative allosteric modulator of several nicotinic acetylcholine receptors.[2] Bupropion does not act as a norepinephrine–dopamine releasing agent.[126] Pharmacological actions of bupropion, to a substantial degree, are due to its active metabolites hydroxybupropion, threo-hydrobupropion, and erythro-hydrobupropion that are present in the blood plasma at comparable or much higher levels.[2] In fact, bupropion could accurately be conceptualized as a prodrug of these metabolites.[2] Overall action of these metabolites, and particularly one enantiomer S,S-hydroxybupropion, is also characterized by inhibition of norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake and nicotinic inhibition (see the chart on the right).[2] Bupropion has no meaningful direct activity at a variety of receptors, including α- and β-adrenergic, dopamine, serotonin, histamine, and muscarinic acetylcholine receptors.[20]

The occupancy of dopamine transporter (DAT) by bupropion (300 mg/day) and its metabolites in the human brain as measured by several positron emission tomography (PET) studies is approximately 20%, with a mean occupancy range of about 14 to 26%.[127][28][29][30] For comparison, the NDRI methylphenidate at therapeutic doses is thought to occupy greater than 50% of DAT sites.[30] In accordance with its low DAT occupancy, no measurable dopamine release in the human brain was detected with bupropion (one 150 mg dose) in a PET study.[127][28][29][128] Bupropion has also been shown to increase striatal VMAT2, though it is unknown if this effect is more pronounced than other DRIs.[129] These findings raise questions about the role of dopamine reuptake inhibition in the pharmacology of bupropion, and suggest that other actions may be responsible for its therapeutic effects.[127][28][30][29] No data are available on occupancy of the norepinephrine transporter (NET) by bupropion and its metabolites.[127][28] However, due to the increased exposure of hydroxybupropion over bupropion itself, which has higher affinity for the NET than the DAT,[130] bupropion's overall pharmacological profile in humans may end up making it effectively more of a norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor than a dopamine reuptake inhibitor.[31][32] Accordingly, the clinical effects of bupropion are more consistent with noradrenergic activity than with dopaminergic actions.[31][32]

Bupropion has been claimed to be a sigma σ1 receptor agonist.[131][132] Its antidepressant-like effects in rodents depend on σ1 receptor activation.[131][132][133] They are enhanced and inhibited by σ1 receptor agonists and antagonists, respectively.[131][132][133] However, no data on the binding or functional effects of bupropion at the human sigma receptors seem to be available.[117][118][119] In any case, bupropion has been reported to bind to rodent σ1 receptors with IC50 values of 580 to 2,100 nM.[134] In contrast to many other phenethylamines and amphetamines,[135] bupropion is not an agonist of the trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1).[136][137][138][139]

Bupropion has been found to have a mixture of anti-inflammatory and pro-inflammatory activity through modulation of the immune system.[140][141][142][143][144][145][146] One such mechanism underlying these effects may be reduced levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα).[140][146][147] The catecholaminergic actions of bupropion may be involved in its immunomodulatory effects.[147]

| Bupropion | R,R- Hydroxy bupropion |

S,S- Hydroxy bupropion |

Threo- hydro bupropion |

Erythro- hydro bupropion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure and half-life | |||||

| AUC relative to bupropion[148][149] |

1 | 23.8 | 0.6 | 11.2 | 2.5 |

| Half-life[15] | 1.04 h | 19 h | 15 h | 31 h | 22 h |

| Inhibition IC50 (μM) in human cells, unless noted otherwise (Lesser values indicate greater potency.) | |||||

| DAT, uptake[130] | 0.66 | inactive | 0.63 | 47 (rat)[150] | no data |

| NET, uptake[130] | 1.85 | 9.9 | 0.24 | 16 (rat)[150] | no data |

| SERT, uptake[130] | inactive | inactive | inactive | 67 (rat)[150] | no data |

| α3β4 nicotinic[130] | 1.8 | 6.5 | 11 | 14 (rat)[151] | no data |

| α4β2 nicotinic[152] | 12 | 31 | 3.3 | no data | no data |

| α1β1γδ nicotinic[152] | 7.9 | 7.6 | 28 | no data | no data |

| 5-HT3A[153][154] | 87 (mouse) | 113 | no data | no data | no data |

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]

After oral administration, bupropion is rapidly and completely absorbed reaching the peak blood plasma concentration after 1.5 hours (tmax). Sustained-release (SR) and extended-release (XL) formulations have been designed to slow down absorption resulting in tmax of 3 hours and 5 hours, respectively.[109] Absolute bioavailability of bupropion is unknown but is presumed to be low, at 5–20%, due to the first-pass metabolism. As for the relative bioavailability of the formulations, XL formulation has lower bioavailability (68%) compared to SR formulation and immediate release bupropion.[2]

Bupropion is metabolized in the body by a variety of pathways. The oxidative pathways are by cytochrome P450 isoenzymes CYP2B6 leading to R,R- and S,S-hydroxybupropion and, to a lesser degree, CYP2C19 leading to 4'-hydroxybupropion. The reductive pathways are by 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 in the liver and AKR7A2/AKR7A3 in the intestine leading to threo-hydrobupropion and by yet unknown enzyme leading to erythro-hydrobupropion.[2]

The metabolism of bupropion is highly variable: the effective doses of bupropion received by persons who ingest the same amount of the drug may differ by as much as 5.5 times (with a half-life of 12–30 hours), while the effective doses of hydroxybupropion may differ by as much as 7.5 times (with a half-life of 15–25 hours).[10][155][156] Based on this, some researchers have advocated monitoring of the blood level of bupropion and hydroxybupropion.[157]

The metabolism of bupropion also seems to follow biphasic pharmacokinetics: the redistribution alpha phase with half-life of about 1 hour[158] precedes the metabolism beta phase of about 12-30 hours. This might explain why abuse is unfeasible due to a short "high", as well as support the use of extended-release formulas to maintain a consistent concentration of bupropion.

The metabolism of bupropion is highly species-dependent.[159][160][161] As an example, oral bupropion results in hydroxybupropion levels that are 16-fold higher than those of bupropion itself in humans, whereas in rats, oral bupropion results in levels of bupropion that are 3.4-fold higher than those of hydroxybupropion.[159] The species-dependent metabolism of bupropion is thought to be involved in species differences in its pharmacodynamic effects.[159][160][161] For example, bupropion produces psychostimulant-like and reinforcing effects in rodents, whereas oral bupropion at therapeutic doses seems to have much less or no potential for such effects in humans.[162]

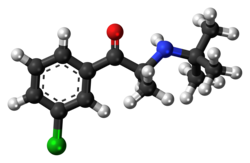

Chemistry

[edit]Bupropion is an aminoketone that belongs to the class of substituted cathinones and the more general class of substituted phenethylamines.[33][34] It is also known structurally as 3-chloro-N-tert-butyl-β-keto-α-methylphenethylamine, 3-chloro-N-tert-butyl-β-ketoamphetamine, or 3-chloro-N-tert-butylcathinone. The clinically used bupropion is racemic, which is a mixture of two enantiomers: S-bupropion and R-bupropion. Although the optical isomers on bupropion can be separated, they rapidly racemize under physiological conditions.[2][163]

Bupropion is a small-molecule compound with the molecular formula C13H18ClNO and a molecular weight of 239.74 g/mol.[164][165] It is a highly lipophilic compound,[2] with an experimental log P of 3.6.[164][165] Pharmaceutically, bupropion is used mainly as the hydrochloride salt but also to a lesser extent as the hydrobromide salt.[10][11][166]

A number of analogues of bupropion exist, such as hydroxybupropion, radafaxine, and manifaxine, among others.[159]

There have been reported cases of false-positive urine amphetamine tests in persons taking bupropion.[167][168][169]

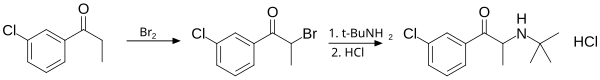

Synthesis

[edit]It is synthesized in two chemical steps starting from 3'-chloro-propiophenone. The alpha position adjacent to the ketone is first brominated followed by nucleophilic displacement of the resulting alpha-bromoketone with t-butylamine and treated with hydrochloric acid to give bupropion as the hydrochloride salt in 75–85% overall yield.[35][170]

This diagram shows the synthesis of bupropion via 3'-chloro-propiophenone.

|

History

[edit]

Bupropion was invented by Nariman Mehta of Burroughs Wellcome (now GlaxoSmithKline) in 1969, and the US patent for it was granted in 1974.[35] It was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as an antidepressant on 30 December 1985, and marketed under the name Wellbutrin.[36][171] However, a significant incidence of seizures at the originally recommended dosage (400–600 mg/day) caused the withdrawal of the drug in 1986. Subsequently, the risk of seizures was found to be highly dose-dependent, and bupropion was re-introduced to the market in 1989 with a lower maximum recommended daily dose of 450 mg/day.[172]

In 1996, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a sustained-release formulation of alcohol-resistant bupropion called Wellbutrin SR, intended to be taken twice a day (as compared with three times a day for immediate-release Wellbutrin).[173] In 2003, the FDA approved another sustained-release formulation called Wellbutrin XL, intended for once-daily dosing.[174] Wellbutrin SR and XL are available in generic form in the United States and Canada. In 1997, bupropion was approved by the FDA for use as a smoking cessation aid under the name Zyban.[175][173] In 2006, Wellbutrin XL was similarly approved as a treatment for seasonal affective disorder.[176][177]

In October 2007, two providers of consumer information on nutritional products and supplements, ConsumerLab.com and The People's Pharmacy, released the results of comparative tests of different brands of bupropion.[178] The People's Pharmacy received multiple reports of increased side effects and decreased efficacy of generic bupropion, which prompted it to ask ConsumerLab.com to test the products in question. The tests showed that "one of a few generic versions of Wellbutrin XL 300 mg, sold as Budeprion XL 300 mg, didn't perform the same as the brand-name pill in the lab."[179] The FDA investigated these complaints and concluded that Budeprion XL is equivalent to Wellbutrin XL in regard to bioavailability of bupropion and its main active metabolite hydroxybupropion. The FDA also said that coincidental natural mood variation is the most likely explanation for the apparent worsening of depression after the switch from Wellbutrin XL to Budeprion XL.[180] On 3 October 2012, however, the FDA reversed this opinion, announcing that "Budeprion XL 300 mg fails to demonstrate therapeutic equivalence to Wellbutrin XL 300 mg."[181] The FDA did not test the bioequivalence of any of the other generic versions of Wellbutrin XL 300 mg, but requested that the four manufacturers submit data on this question to the FDA by March 2013.[181] As of October 2013[update] the FDA has made determinations on the formulations from some manufacturers not being bioequivalent.[181]

In April 2008, the FDA approved a formulation of bupropion as a hydrobromide salt instead of a hydrochloride salt, to be sold under the name Aplenzin by Sanofi-Aventis.[12][182][183]

In 2009, the FDA issued a health advisory warning that the prescription of bupropion for smoking cessation has been associated with reports of unusual behavior changes, agitation, and hostility. Some people, according to the advisory, have become depressed or have had their depression worsen, have had thoughts about suicide or dying, or have attempted suicide.[184] This advisory was based on a review of anti-smoking products that identified 75 reports of "suicidal adverse events" for bupropion over ten years.[185] Based on the results of follow-up trials this warning was removed in 2016.[186]

In 2012, the US Justice Department announced that GlaxoSmithKline had agreed to plead guilty and pay a $3 billion fine, in part for promoting the unapproved use of Wellbutrin for weight loss and sexual dysfunction.[187]

In 2017, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) recommended suspending a number of nationally approved medicines due to misrepresentation of bioequivalence study data by Micro Therapeutic Research Labs in India.[188] The products recommended for suspension included several 300 mg modified-release bupropion tablets.[189]

Following EMA's call for an industry-wide review of medicines for the possible presence of nitrosamines,[190] GlaxoSmithKline paused batch release and distribution of bupropion 150 mg tablets in November 2022. In July 2023, EMA raised the acceptable daily intake of nitrosamine impurities, leading GlaxoSmithKline to announce that distribution of bupropion 150 mg tablets would resume "across the EU and Europe" by the end of 2023.[191]

Society and culture

[edit]Recreational use

[edit]While bupropion demonstrates some potential for misuse, this potential is less than of other commonly used stimulants, being limited by features of its pharmacology.[192] Case reports describe the misuse of bupropion as producing a "high" similar to cocaine or amphetamine usage but with less intensity. Bupropion misuse is uncommon.[192] There have been some anecdotal and case-study reports of bupropion abuse, but the bulk of evidence indicates that the subjective effects of bupropion when taken orally are markedly different from those of addictive stimulants such as cocaine or amphetamine.[193] However, bupropion, by non-conventional routes of administration like injection or insufflation, has been reported to be misused in the United States and Canada, notably in prisons.[194][195][196][197]

Legal status

[edit]In Russia bupropion is banned as a narcotic drug, due to it being a derivative of methcathinone.[198] In Australia, France, and the UK, smoking cessation is the only licensed use of bupropion, and no generics are marketed.[199][200][201]

Brand names

[edit]Brand names include Wellbutrin,[10][11] Aplenzin,[12] Budeprion, Buproban, buprapan, Forfivo, Voxra, Zyban,[8] Bupron, Bupisure, Bupep, Smoquite, Elontril, Oribion and Buxon.[citation needed]

Research

[edit]Bupropion has been studied limitedly in the treatment of social anxiety disorder.[202][203][204]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Bupropion Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Costa R, Oliveira NG, Dinis-Oliveira RJ (August 2019). "Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic of bupropion: integrative overview of relevant clinical and forensic aspects". Drug Metabolism Reviews. 51 (3): 293–313. doi:10.1080/03602532.2019.1620763. PMID 31124380. S2CID 163167323.

- ^ a b c Fava M, Rush AJ, Thase ME, Clayton A, Stahl SM, Pradko JF, et al. (2005). "15 years of clinical experience with bupropion HCl: from bupropion to bupropion SR to bupropion XL". Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 7 (3): 106–113. doi:10.4088/pcc.v07n0305. PMC 1163271. PMID 16027765.

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ "TGA eBS – Product and Consumer Medicine Information Licence". Archived from the original on 7 December 2016. Retrieved 9 January 2023.

- ^ Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency (Anvisa) (31 March 2023). "RDC Nº 784 – Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 – Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 4 April 2023). Archived from the original on 3 August 2023. Retrieved 3 August 2023.

- ^ "Wellbutrin Product information". Health Canada. 25 April 2012. Archived from the original on 9 January 2023. Retrieved 9 January 2023.

- ^ a b "Zyban Product information". Health Canada. 25 April 2012. Archived from the original on 9 January 2023. Retrieved 9 January 2023.

- ^ "Zyban 150 mg prolonged release tablets – Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 21 April 2022. Archived from the original on 9 January 2023. Retrieved 9 January 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r "Wellbutrin SR – bupropion hydrochloride tablet, film coated". DailyMed. 5 November 2019. Archived from the original on 4 June 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Wellbutrin XL- bupropion hydrochloride tablet, extended release". DailyMed. 4 March 2022. Archived from the original on 9 January 2023. Retrieved 9 January 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Aplenzin – bupropion hydrobromide tablet, extended-release". DailyMed. 2 June 2020. Archived from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- ^ "Bupropion hydrochloride EPAR". European Medicines Agency. 17 September 2018. Archived from the original on 18 August 2022. Retrieved 7 March 2023.

- ^ a b c "Zyban 150 mg prolonged release film-coated tablets – Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC)". electronic Medicines Compendium. GlaxoSmithKline UK. 1 August 2013. Archived from the original on 20 July 2017. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- ^ a b Masters AR, Gufford BT, Lu JB, Metzger IF, Jones DR, Desta Z (August 2016). "Chiral Plasma Pharmacokinetics and Urinary Excretion of Bupropion and Metabolites in Healthy Volunteers". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 358 (2): 230–238. doi:10.1124/jpet.116.232876. PMC 4959100. PMID 27255113.

- ^ a b World Health Organization (2000). "International nonproprietary names for pharmaceutical substances (INN) : proposed international nonproprietary names : list 83". WHO Drug Information. 14 (2). hdl:10665/58135.

- ^ Sweetman S (2011). Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference (37th ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. p. 402. ISBN 978-0-85369-982-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Patel K, Allen S, Haque MN, Angelescu I, Baumeister D, Tracy DK (April 2016). "Bupropion: a systematic review and meta-analysis of effectiveness as an antidepressant". Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology. 6 (2): 99–144. doi:10.1177/2045125316629071. PMC 4837968. PMID 27141292.

- ^ a b Arandjelovic K, Eyre HA, Lavretsky H (October 2016). "Clinicians' Views on Treatment-Resistant Depression: 2016 Survey Reports". The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 24 (10): 913–917. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2016.05.010. PMC 5540329. PMID 27591914.

- ^ a b c Dhillon S, Yang LP, Curran MP (2008). "Bupropion: a review of its use in the management of major depressive disorder". Drugs. 68 (5): 653–689. doi:10.2165/00003495-200868050-00011. PMID 18370448. S2CID 195687060.

- ^ a b Baldwin DS, Papakostas GI (2006). "Symptoms of fatigue and sleepiness in major depressive disorder". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 67 (Suppl 6): 9–15. PMID 16848671.

- ^ Steinert T, Fröscher W (July 2018). "Epileptic Seizures Under Antidepressive Drug Treatment: Systematic Review". Pharmacopsychiatry. 51 (4): 121–135. doi:10.1055/s-0043-117962. PMID 28850959. S2CID 22436728.

- ^ a b Wilens TE, Hammerness PG, Biederman J, Kwon A, Spencer TJ, Clark S, et al. (February 2005). "Blood pressure changes associated with medication treatment of adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 66 (2): 253–259. doi:10.4088/jcp.v66n0215. PMID 15705013.

- ^ a b Voican CS, Corruble E, Naveau S, Perlemuter G (April 2014). "Antidepressant-induced liver injury: a review for clinicians". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 171 (4): 404–415. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13050709. PMID 24362450.

- ^ a b c Kumar S, Kodela S, Detweiler JG, Kim KY, Detweiler MB (November–December 2011). "Bupropion-induced psychosis: folklore or a fact? A systematic review of the literature". General Hospital Psychiatry. 33 (6): 612–617. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2011.07.001. PMID 21872337.

- ^ a b Nelson JC, Spyker DA (May 2017). "Morbidity and Mortality Associated With Medications Used in the Treatment of Depression: An Analysis of Cases Reported to U.S. Poison Control Centers, 2000–2014". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 174 (5): 438–450. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16050523. PMID 28135844.

- ^ a b De Vries C, Gadzhanova S, Sykes MJ, Ward M, Roughead E (March 2021). "A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Considering the Risk for Congenital Heart Defects of Antidepressant Classes and Individual Antidepressants". Drug Safety. 44 (3): 291–312. doi:10.1007/s40264-020-01027-x. PMID 33354752. S2CID 229357583. Archived from the original on 7 March 2023. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Eap CB, Gründer G, Baumann P, Ansermot N, Conca A, Corruble E, et al. (October 2021). "Tools for optimising pharmacotherapy in psychiatry (therapeutic drug monitoring, molecular brain imaging and pharmacogenetic tests): focus on antidepressants" (PDF). The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry. 22 (8): 561–628. doi:10.1080/15622975.2021.1878427. PMID 33977870. S2CID 234472488. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 May 2022. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d Carroll FI, Blough BE, Mascarella SW, Navarro HA, Lukas RJ, Damaj MI (2014). "Bupropion and bupropion analogs as treatments for CNS disorders". Emerging Targets & Therapeutics in the Treatment of Psychostimulant Abuse. Advances in Pharmacology. Vol. 69. Academic Press. pp. 177–216. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-420118-7.00005-6. ISBN 978-0-12-420118-7. PMID 24484978.

- ^ a b c d e f Verbeeck W, Bekkering GE, Van den Noortgate W, Kramers C (October 2017). "Bupropion for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 (10): CD009504. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009504.pub2. PMC 6485546. PMID 28965364.

- ^ a b c DeBattista C (16 June 2022). "Other Antidepressants: Bupropion, Mirtazapine, and Trazodone". In Nemeroff CB, Schatzberg AF, Rasgon N, Strakowski SM (eds.). The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Mood Disorders, Second Edition. American Psychiatric Pub. pp. 365–374. ISBN 978-1-61537-331-4. OCLC 1249799493. Archived from the original on 8 March 2023. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ a b c Gautam M, Patel S, Zarkowski P (January 2022). "Practice patterns of bupropion co-prescription with antipsychotic medications". J Addict Dis. 40 (4): 481–488. doi:10.1080/10550887.2022.2028531. PMID 35068363. S2CID 246238087.

- ^ a b "Bupropion". PubChem. United States National Library of Medicine – National Center for Biotechnology Information. 28 July 2018. Archived from the original on 29 July 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- ^ a b Dye LR, Murphy C, Calello DP, Levine MD, Skolnik A (2017). Case Studies in Medical Toxicology: From the American College of Medical Toxicology. Springer. p. 85. ISBN 978-3-319-56449-4. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- ^ a b c Mehta NB (25 June 1974). "United States Patent 3,819,706: Meta-chloro substituted α-butylamino-propiophenones". USPTO. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- ^ a b "Wellbutrin approval package" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 30 December 1985. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2022". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 30 August 2024. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ "Bupropion Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013–2022". ClinCalc. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ World Health Organization (2023). The selection and use of essential medicines 2023: web annex A: World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 23rd list (2023). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/371090. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.

- ^ Majeed A, Xiong J, Teopiz KM, Ng J, Ho R, Rosenblat JD, et al. (March 2021). "Efficacy of dextromethorphan for the treatment of depression: a systematic review of preclinical and clinical trials". Expert Opinion on Emerging Drugs. 26 (1): 63–74. doi:10.1080/14728214.2021.1898588. PMID 33682569. S2CID 232141396.

- ^ Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, Geddes JR, Higgins JP, Churchill R, et al. (February 2009). "Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 12 new-generation antidepressants: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis". Lancet. 373 (9665): 746–758. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60046-5. PMID 19185342. S2CID 35858125.

- ^ a b c d Monden R, Roest AM, van Ravenzwaaij D, Wagenmakers EJ, Morey R, Wardenaar KJ, et al. (August 2018). "The comparative evidence basis for the efficacy of second-generation antidepressants in the treatment of depression in the US: A Bayesian meta-analysis of Food and Drug Administration reviews" (PDF). Journal of Affective Disorders. 235: 393–398. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2018.04.040. hdl:11370/842b1441-d0f3-4797-b95b-3a6a72262150. PMID 29677603. S2CID 5011570. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 February 2022. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ^ a b c Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, Chaimani A, Atkinson LZ, Ogawa Y, et al. (April 2018). "Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis". Lancet. 391 (10128): 1357–1366. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32802-7. PMC 5889788. PMID 29477251.

- ^ a b c Hengartner MP, Jakobsen JC, Sørensen A, Plöderl M (2020). "Efficacy of new-generation antidepressants assessed with the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale, the gold standard clinician rating scale: A meta-analysis of randomised placebo-controlled trials". PLOS ONE. 15 (2): e0229381. Bibcode:2020PLoSO..1529381H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0229381. PMC 7043778. PMID 32101579.

- ^ a b Stone MB, Yaseen ZS, Miller BJ, Richardville K, Kalaria SN, Kirsch I (August 2022). "Response to acute monotherapy for major depressive disorder in randomized, placebo controlled trials submitted to the US Food and Drug Administration: individual participant data analysis". BMJ. 378: e067606. doi:10.1136/bmj-2021-067606. PMC 9344377. PMID 35918097.

- ^ Turner EH, Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, de Vries YA (January 2022). "Selective publication of antidepressant trials and its influence on apparent efficacy: Updated comparisons and meta-analyses of newer versus older trials". PLOS Med. 19 (1): e1003886. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1003886. PMC 8769343. PMID 35045113.

- ^ Turner EH, Matthews AM, Linardatos E, Tell RA, Rosenthal R (January 2008). "Selective publication of antidepressant trials and its influence on apparent efficacy". N Engl J Med. 358 (3): 252–60. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa065779. PMID 18199864.

- ^ Gartlehner G, Nussbaumer-Streit B, Gaynes BN, Forneris CA, Morgan LC, Greenblatt A, et al. (March 2019). "Second-generation antidepressants for preventing seasonal affective disorder in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3 (4): CD011268. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011268.pub3. PMC 6422318. PMID 30883669.

- ^ Li DJ, Tseng PT, Chen YW, Wu CK, Lin PY (March 2016). "Significant Treatment Effect of Bupropion in Patients With Bipolar Disorder but Similar Phase-Shifting Rate as Other Antidepressants: A Meta-Analysis Following the PRISMA Guidelines". Medicine. 95 (13): e3165. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000003165. PMC 4998539. PMID 27043678.

- ^ Clayton AH (2003). "Antidepressant-Associated Sexual Dysfunction: A Potentially Avoidable Therapeutic Challenge". Primary Psychiatry. 10 (1): 55–61. Archived from the original on 4 June 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2013.

- ^ a b Papakostas GI, Stahl SM, Krishen A, Seifert CA, Tucker VL, Goodale EP, et al. (August 2008). "Efficacy of bupropion and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in the treatment of major depressive disorder with high levels of anxiety (anxious depression): a pooled analysis of 10 studies". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 69 (8): 1287–1292. doi:10.4088/JCP.v69n0812. PMID 18605812. S2CID 25267685.

- ^ Naguy A, Badr BHM (October 2022). "Bupropion-myth-busting!". CNS Spectr. 27 (5): 545–546. doi:10.1017/S1092852921000365. PMID 33843549. S2CID 233212535.

- ^ Ruberto VL, Jha MK, Murrough JW (June 2020). "Pharmacological Treatments for Patients with Treatment-Resistant Depression". Pharmaceuticals. 13 (6): 116. doi:10.3390/ph13060116. PMC 7345023. PMID 32512768.

- ^ Wilkes S (2008). "The use of bupropion SR in cigarette smoking cessation". International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 3 (1): 45–53. doi:10.2147/copd.s1121. PMC 2528204. PMID 18488428.

- ^ a b Hajizadeh A, Howes S, Theodoulou A, Klemperer E, Hartmann-Boyce J, Livingstone-Banks J, et al. (May 2023). "Antidepressants for smoking cessation". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2023 (5): CD000031. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000031.pub6. PMC 10207863. PMID 37230961.

- ^ Wu P, Wilson K, Dimoulas P, Mills EJ (December 2006). "Effectiveness of smoking cessation therapies: a systematic review and meta-analysis". BMC Public Health. 6: 300. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-6-300. PMC 1764891. PMID 17156479.

- ^ a b c Mooney ME, Sofuoglu M (July 2006). "Bupropion for the treatment of nicotine withdrawal and craving". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 6 (7): 965–981. doi:10.1586/14737175.6.7.965. PMID 16831112. S2CID 19195413.

- ^ Rosen LJ, Galili T, Kott J, Goodman M, Freedman LS (May 2018). "Diminishing benefit of smoking cessation medications during the first year: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Addiction. 113 (5): 805–816. doi:10.1111/add.14134. PMC 5947828. PMID 29377409.

- ^ Livingstone-Banks J, Norris E, Hartmann-Boyce J, West R, Jarvis M, Chubb E, et al. (October 2019). "Relapse prevention interventions for smoking cessation". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (10). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003999.pub6. PMC 6816175. PMID 31684681.

- ^ Patnode CD, Henderson JT, Coppola EL, Melnikow J, Durbin S, Thomas RG (January 2021). "Interventions for Tobacco Cessation in Adults, Including Pregnant Persons: Updated Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force". JAMA. 325 (3): 280–298. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.23541. PMID 33464342.

- ^ Selph S, Patnode C, Bailey SR, Pappas M, Stoner R, Chou R (April 2020). "Primary Care-Relevant Interventions for Tobacco and Nicotine Use Prevention and Cessation in Children and Adolescents: Updated Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force". JAMA. 323 (16): 1599–1608. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.3332. PMID 32343335.

- ^ Claire R, Chamberlain C, Davey MA, Cooper SE, Berlin I, Leonardi-Bee J, et al. (March 2020). "Pharmacological interventions for promoting smoking cessation during pregnancy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (3): CD010078. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010078.pub3. PMC 7059898. PMID 32129504.

- ^ Wolraich ML, Hagan JF, Allan C, Chan E, Davison D, Earls M, et al. (October 2019). "Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Children and Adolescents". Pediatrics. 144 (4): e20192528. doi:10.1542/peds.2019-2528. PMC 7067282. PMID 31570648.

- ^ Elliott J, Johnston A, Husereau D, Kelly SE, Eagles C, Charach A, et al. (2020). "Pharmacologic treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults: A systematic review and network meta-analysis". PLOS ONE. 15 (10): e0240584. Bibcode:2020PLoSO..1540584E. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0240584. PMC 7577505. PMID 33085721.

- ^ Cortese S, Adamo N, Del Giovane C, Mohr-Jensen C, Hayes AJ, Carucci S, et al. (September 2018). "Comparative efficacy and tolerability of medications for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children, adolescents, and adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis". The Lancet. Psychiatry. 5 (9): 727–738. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30269-4. PMC 6109107. PMID 30097390.

- ^ Ng QX (March 2017). "A Systematic Review of the Use of Bupropion for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Children and Adolescents". Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 27 (2): 112–116. doi:10.1089/cap.2016.0124. PMID 27813651.

- ^ a b Wilens TE, Morrison NR, Prince J (October 2011). "An update on the pharmacotherapy of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 11 (10): 1443–1465. doi:10.1586/ern.11.137. PMC 3229037. PMID 21955201.

- ^ Serretti A, Chiesa A (June 2009). "Treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction related to antidepressants: a meta-analysis". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 29 (3): 259–266. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181a5233f. PMID 19440080. S2CID 1663570.

- ^ Stahl SM, Pradko JF, Haight BR, Modell JG, Rockett CB, Learned-Coughlin S (2004). "A Review of the Neuropharmacology of Bupropion, a Dual Norepinephrine and Dopamine Reuptake Inhibitor". Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 6 (4): 159–166. doi:10.4088/PCC.v06n0403. PMC 514842. PMID 15361919.

- ^ Basson R, Gilks T (2018). "Women's sexual dysfunction associated with psychiatric disorders and their treatment". Women's Health. 14: 1745506518762664. doi:10.1177/1745506518762664. PMC 5900810. PMID 29649948.

- ^ Clayton AH, Kingsberg SA, Goldstein I (June 2018). "Evaluation and Management of Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder". Sexual Medicine. 6 (2): 59–74. doi:10.1016/j.esxm.2018.01.004. PMC 5960024. PMID 29523488.

- ^ Goldstein I, Kim NN, Clayton AH, DeRogatis LR, Giraldi A, Parish SJ, et al. (January 2017). "Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder: International Society for the Study of Women's Sexual Health (ISSWSH) Expert Consensus Panel Review". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 92 (1): 114–128. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.09.018. PMID 27916394.

- ^ Razali NA, Sidi H, Choy CL, Ross NA, Baharudin A, Das S (February 2022). "The Role of Bupropion in the Treatment of Women with Sexual Desire Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Curr Neuropharmacol. 20 (10): 1941–1955. doi:10.2174/1570159X20666220222145735. PMC 9886814. PMID 35193485. S2CID 247057961.

- ^ a b Li Z, Maglione M, Tu W, Mojica W, Arterburn D, Shugarman LR, et al. (April 2005). "Meta-analysis: pharmacologic treatment of obesity". Annals of Internal Medicine. 142 (7): 532–546. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-142-7-200504050-00012. PMID 15809465.

- ^ "Drug Approval Package: Contrave (naltrexone hydrochloride/bupropion hydrochloride) Extended-Release Tablets NDA #200063". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 4 June 2020. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ^ "Contrave Extended-Release – naltrexone hydrochloride and bupropion hydrochloride tablet, extended-release". DailyMed. 26 April 2019. Archived from the original on 4 June 2020. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ^ Kampman KM (June 2008). "The search for medications to treat stimulant dependence". Addiction Science & Clinical Practice. 4 (2): 28–35. doi:10.1151/ascp084228 (inactive 11 November 2024). PMC 2797110. PMID 18497715.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ Cao DN, Shi JJ, Hao W, Wu N, Li J (June 2016). "Advances and challenges in pharmacotherapeutics for amphetamine-type stimulants addiction". European Journal of Pharmacology. 780: 129–135. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2016.03.040. PMID 27018393.

- ^ Akbar D, Rhee TG, Ceban F, Ho R, Teopiz KM, Cao B, et al. (October 2023). "Dextromethorphan-Bupropion for the Treatment of Depression: A Systematic Review of Efficacy and Safety in Clinical Trials". CNS Drugs. 37 (10): 867–881. doi:10.1007/s40263-023-01032-5. PMID 37792265.

- ^ Mikocka-Walus AA, Turnbull DA, Moulding NT, Wilson IG, Andrews JM, Holtmann GJ (September 2006). "Antidepressants and inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review". Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health. 2: 24. doi:10.1186/1745-0179-2-24. PMC 1599716. PMID 16984660.

- ^ Thorkelson G, Bielefeldt K, Szigethy E (June 2016). "Empirically Supported Use of Psychiatric Medications in Adolescents and Adults with IBD". Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 22 (6): 1509–1522. doi:10.1097/MIB.0000000000000734. PMID 27167571.

- ^ Eskeland S, Halvorsen JA, Tanum L (August 2017). "Antidepressants have Anti-inflammatory Effects that may be Relevant to Dermatology: A Systematic Review". Acta Dermato-Venereologica. 97 (8): 897–905. doi:10.2340/00015555-2702. hdl:10852/63759. PMID 28512664.

- ^ Urquhart DM, Hoving JL, Assendelft WW, Roland M, van Tulder MW (January 2008). Urquhart DM (ed.). "Antidepressants for non-specific low back pain". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008 (1): CD001703. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001703.pub3. PMC 7025781. PMID 18253994.

- ^ Ono T, Takenoshita S, Nishino S (September 2022). "Pharmacologic Management of Excessive Daytime Sleepiness". Sleep Med Clin. 17 (3): 485–503. doi:10.1016/j.jsmc.2022.06.012. PMID 36150809.

- ^ Nishino S, Kotorii N (2016). "Overview of Management of Narcolepsy". Narcolepsy. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 285–305. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-23739-8_21. ISBN 978-3-319-23738-1.

- ^ Rye DB, Dihenia B, Bliwise DL (1998). "Reversal of atypical depression, sleepiness, and REM-sleep propensity in narcolepsy with bupropion". Depress Anxiety. 7 (2): 92–95. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6394(1998)7:2<92::AID-DA9>3.0.CO;2-7. PMID 9614600.

- ^ Goksan B, Mercan S, Karamustafalioglu O (2005). "Bupropion is effective in depression in narcolepsy". Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 9 (4): 289–291. doi:10.1080/13651500500241454. PMID 24930928.

- ^ a b c Hailwood JM (27 September 2018). Novel approaches towards pharmacological enhancement of motivation (Thesis). University of Cambridge. pp. 13–14. doi:10.17863/CAM.40216.

Bupropion also acts as a dopamine reuptake inhibitor (Dwoskin et al. 2006), and has been used as a treatment for depression as well as a smoking cessation aid (Stahl et al. 2004). Bupropion has been shown to produce a dose-dependent increase in PR breakpoints (Bruijnzeel & Markou 2003). Furthermore, systemic administration of bupropion increases the selection of the high-effort, high-reward option in a PR-choice task in rats (Randall, Lee, Podurgiel, et al. 2014). Bupropion is also effective at rescuing motivational impairments in rodents. Administration of bupropion can rescue deficits in effort-related decision-making induced by pre-treatment with tetrabenazine (Randall, Lee, Nunes, et al. 2014; Nunes, Randall, Hart, et al. 2013) and the proinflammatory cytokine interleukin-6 (Yohn, Arif, et al. 2016). Bupropion has been reported to improve symptoms of apathy in cases of acquired brain injury, major depression (Corcoran et al. 2004), and frontotemporal dementia (Lin et al. 2016). However, several larger placebo-controlled studies suggest only limited effects of bupropion. In a study of 40 patients with schizophrenia, bupropion was found to have no significant effect on apathy or negative symptoms as a whole (Yassini et al. 2014). Furthermore, in a recent RCT of bupropion in HD, apathy was not significantly affected by the drug (Gelderblom et al. 2017). It is not clear whether bupropion lacks clinical efficacy, whether bupropion as a whole is not effective at treating motivational impairments, or simply not effective in the clinical populations tested.

- ^ Marin RS, Wilkosz PA (2005). "Disorders of diminished motivation". J Head Trauma Rehabil. 20 (4): 377–88. doi:10.1097/00001199-200507000-00009. PMID 16030444.

- ^ Lyonga Ngonge A, Nyange C, Ghali JK (February 2024). "Novel pharmacotherapeutic options for the treatment of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome". Expert Opin Pharmacother. 25 (2): 181–188. doi:10.1080/14656566.2024.2319224. PMID 38465412.

- ^ Vyas R, Nesheiwat Z, Ruzieh M, Ammari Z, Al-Sarie M, Grubb B (August 2020). "Bupropion in the treatment of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): a single-center experience". J Investig Med. 68 (6): 1156–1158. doi:10.1136/jim-2020-001272. PMID 32606041.

- ^ "Auvelity- dextromethorphan hydrobromide, bupropion hydrochloride tablet, multilayer, extended-release". DailyMed. 18 September 2024. Retrieved 17 October 2024.

- ^ Majeed A, Xiong J, Teopiz KM, Ng J, Ho R, Rosenblat JD, et al. (March 2021). "Efficacy of dextromethorphan for the treatment of depression: a systematic review of preclinical and clinical trials". Expert Opinion on Emerging Drugs. 26 (1): 63–74. doi:10.1080/14728214.2021.1898588. PMID 33682569. S2CID 232141396.

- ^ Alberti S, Chiesa A, Andrisano C, Serretti A (June 2015). "Insomnia and somnolence associated with second-generation antidepressants during the treatment of major depression: a meta-analysis". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 35 (3): 296–303. doi:10.1097/JCP.0000000000000329. PMID 25874915. S2CID 33102792. Archived from the original on 8 March 2023. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ Telang S, Walton C, Olten B, Bloch MH (August 2018). "Meta-analysis: Second generation antidepressants and headache". Journal of Affective Disorders. 236: 60–68. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2018.04.047. PMID 29715610. S2CID 19196303.

- ^ Kittle J, Lopes RD, Huang M, Marquess ML, Wilson MD, Ascher J, et al. (October 2017). "Cardiovascular adverse events in the drug-development program of bupropion for smoking cessation: A systematic retrospective adjudication effort". Clinical Cardiology. 40 (10): 899–906. doi:10.1002/clc.22744. PMC 6490529. PMID 28605035.

- ^ Grandi SM, Shimony A, Eisenberg MJ (December 2013). "Bupropion for smoking cessation in patients hospitalized with cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". The Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 29 (12): 1704–1711. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2013.09.014. PMID 24267809.

- ^ Pisani F, Oteri G, Costa C, Di Raimondo G, Di Perri R (2002). "Effects of psychotropic drugs on seizure threshold". Drug Safety. 25 (2): 91–110. doi:10.2165/00002018-200225020-00004. PMID 11888352. S2CID 25290793.

- ^ Wu A, Khawaja AP, Pasquale LR, Stein JD (January 2020). "A review of systemic medications that may modulate the risk of glaucoma". Eye. 34 (1): 12–28. doi:10.1038/s41433-019-0603-z. PMC 7002596. PMID 31595027.

- ^ "Naltrexone + bupropion (Mysimba). Too risky for only modest weight loss". Prescrire International. 24 (164): 229–233. October 2015. PMID 26594724.

- ^ Herstowska M, Komorowska O, Cubała WJ, Jakuszkowiak-Wojten K, Gałuszko-Węgielnik M, Landowski J (May 2014). "Severe skin complications in patients treated with antidepressants: a literature review". Postepy Dermatologii I Alergologii. 31 (2): 92–97. doi:10.5114/pdia.2014.40930. PMC 4112250. PMID 25097474.

- ^ Goodnick PJ, Jerry J, Parra F (May 2002). "Psychotropic drugs and the ECG: focus on the QTc interval". Expert Opin Pharmacother. 3 (5): 479–498. doi:10.1517/14656566.3.5.479. PMID 11996627.

- ^ Jasiak NM, Bostwick JR (December 2014). "Risk of QT/QTc prolongation among newer non-SSRI antidepressants". Ann Pharmacother. 48 (12): 1620–1628. doi:10.1177/1060028014550645. PMID 25204465.

- ^ Caillier B, Pilote S, Castonguay A, Patoine D, Ménard-Desrosiers V, Vigneault P, et al. (October 2012). "QRS widening and QT prolongation under bupropion: a unique cardiac electrophysiological profile". Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 26 (5): 599–608. doi:10.1111/j.1472-8206.2011.00953.x. PMID 21623902.

- ^ a b Levenson M, Holland C. "Antidepressants and suicidality in adults: statistical evaluation. (Presentation at Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee; December 13, 2006)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 13 May 2007.

- ^ Henssler J, Heinz A, Brandt L, Bschor T (May 2019). "Antidepressant Withdrawal and Rebound Phenomena". Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 116 (20): 355–361. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2019.0355. PMC 6637660. PMID 31288917.

- ^ Taylor D, Carol P, Shitij K (2012). The Maudsley prescribing guidelines in psychiatry. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-470-97969-3.

- ^ White N, Litovitz T, Clancy C (December 2008). "Suicidal antidepressant overdoses: a comparative analysis by antidepressant type". Journal of Medical Toxicology. 4 (4): 238–250. doi:10.1007/BF03161207. PMC 3550116. PMID 19031375.

- ^ a b c d e f Jefferson JW, Pradko JF, Muir KT (November 2005). "Bupropion for major depressive disorder: Pharmacokinetic and formulation considerations". Clinical Therapeutics. 27 (11): 1685–1695. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2005.11.011. PMID 16368442.

- ^ Ketter TA, Jenkins JB, Schroeder DH, Pazzaglia PJ, Marangell LB, George MS, et al. (October 1995). "Carbamazepine but not valproate induces bupropion metabolism". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 15 (5): 327–333. doi:10.1097/00004714-199510000-00004. PMID 8830063.

- ^ a b c "Highlight os Prescribing Information: CONTRAVE (naltrexone hydrochloride and bupropion hydrochloride) extended-release tablets, for oral use" (PDF). Currax Pharmaceuticals LLC. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. August 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 October 2020. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- ^ Todor I, Popa A, Neag M, Muntean D, Bocsan C, Buzoianu A, et al. (2016). "Evaluation of a Potential Metabolism-Mediated Drug-Drug Interaction Between Atomoxetine and Bupropion in Healthy Volunteers". Journal of Pharmacy & Pharmaceutical Sciences. 19 (2): 198–207. doi:10.18433/J3H03R. PMID 27518170.

- ^ Schmid Y, Rickli A, Schaffner A, Duthaler U, Grouzmann E, Hysek CM, et al. (April 2015). "Interactions between bupropion and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine in healthy subjects". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 353 (1): 102–111. doi:10.1124/jpet.114.222356. PMID 25655950. S2CID 14761997.

- ^ a b Protti M, Mandrioli R, Marasca C, Cavalli A, Serretti A, Mercolini L (September 2020). "New-generation, non-SSRI antidepressants: Drug-drug interactions and therapeutic drug monitoring. Part 2: NaSSAs, NRIs, SNDRIs, MASSAs, NDRIs, and others". Medicinal Research Reviews. 40 (5): 1794–1832. doi:10.1002/med.21671. hdl:11585/762375. PMID 32285503. S2CID 215758102.

- ^ Spina E, Santoro V, D'Arrigo C (July 2008). "Clinically relevant pharmacokinetic drug interactions with second-generation antidepressants: an update". Clinical Therapeutics. 30 (7): 1206–1227. doi:10.1016/s0149-2918(08)80047-1. PMID 18691982.

- ^ Feinberg SS (November 2004). "Combining stimulants with monoamine oxidase inhibitors: a review of uses and one possible additional indication". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 65 (11): 1520–1524. doi:10.4088/jcp.v65n1113. PMID 15554766.

- ^ a b Roth BL, Driscol J. "Bupropion – PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved 19 August 2024.

- ^ a b Liu T. "BindingDB BDBM50048392 2-(tert-butylamino)-1-(3-chlorophenyl)propan-1-one::BUPROPION::BUPROPION HYDROCHLORIDE::CHEMBL894::US9944618, Compound ID No. 176". BindingDB. Retrieved 19 August 2024.

- ^ a b "Bupropion – Biological Test Results". PubChem. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 19 August 2024.

- ^ Richelson E, Nelson A (July 1984). "Antagonism by antidepressants of neurotransmitter receptors of normal human brain in vitro". J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 230 (1): 94–102. PMID 6086881.

- ^ Wander TJ, Nelson A, Okazaki H, Richelson E (December 1986). "Antagonism by antidepressants of serotonin S1 and S2 receptors of normal human brain in vitro". Eur J Pharmacol. 132 (2–3): 115–121. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(86)90596-0. PMID 3816971.

- ^ Cusack B, Nelson A, Richelson E (May 1994). "Binding of antidepressants to human brain receptors: focus on newer generation compounds". Psychopharmacology (Berl). 114 (4): 559–565. doi:10.1007/BF02244985. PMID 7855217.

- ^ Tatsumi M, Groshan K, Blakely RD, Richelson E (December 1997). "Pharmacological profile of antidepressants and related compounds at human monoamine transporters". Eur J Pharmacol. 340 (2–3): 249–258. doi:10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01393-9. PMID 9537821.

- ^ Sánchez C, Hyttel J (August 1999). "Comparison of the effects of antidepressants and their metabolites on reuptake of biogenic amines and on receptor binding". Cell Mol Neurobiol. 19 (4): 467–489. doi:10.1023/a:1006986824213. PMID 10379421.

- ^ Damaj MI, Carroll FI, Eaton JB, Navarro HA, Blough BE, Mirza S, et al. (September 2004). "Enantioselective effects of hydroxy metabolites of bupropion on behavior and on function of monoamine transporters and nicotinic receptors". Mol Pharmacol. 66 (3): 675–682. doi:10.1124/mol.104.001313. PMID 15322260.

- ^ Shalabi AR, Walther D, Baumann MH, Glennon RA (June 2017). "Deconstructed Analogues of Bupropion Reveal Structural Requirements for Transporter Inhibition versus Substrate-Induced Neurotransmitter Release". ACS Chemical Neuroscience. 8 (6): 1397–1403. doi:10.1021/acschemneuro.7b00055. PMC 7261150. PMID 28220701.

- ^ a b c d Hart XM, Spangemacher M, Defert J, Uchida H, Gründer G (April 2024). "Update Lessons from PET Imaging Part II: A Systematic Critical Review on Therapeutic Plasma Concentrations of Antidepressants". Ther Drug Monit. 46 (2): 155–169. doi:10.1097/FTD.0000000000001142. PMID 38287888.

- ^ Egerton A, Shotbolt JP, Stokes PR, Hirani E, Ahmad R, Lappin JM, et al. (March 2010). "Acute effect of the anti-addiction drug bupropion on extracellular dopamine concentrations in the human striatum: an [11C]raclopride PET study". NeuroImage. 50 (1): 260–266. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.11.077. PMC 4135078. PMID 19969097.

- ^ Rau KS, Birdsall E, Hanson JE, Johnson-Davis KL, Carroll FI, Wilkins DG, et al. (November 2005). "Bupropion increases striatal vesicular monoamine transport". Neuropharmacology. New Perspectives in Neurotransmitter Transporter Biology. 49 (6): 820–830. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.05.004. PMID 16005476. S2CID 26035635.

- ^ a b c d e Lukas RJ, Muresan AZ, Damaj MI, Blough BE, Huang X, Navarro HA, et al. (June 2010). "Synthesis and characterization of in vitro and in vivo profiles of hydroxybupropion analogues: aids to smoking cessation". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 53 (12): 4731–4748. doi:10.1021/jm1003232. PMC 2895766. PMID 20509659.

- ^ a b c Sałaciak K, Pytka K (January 2022). "Revisiting the sigma-1 receptor as a biological target to treat affective and cognitive disorders". Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 132: 1114–1136. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.10.037. PMC 8559442. PMID 34736882.

- ^ a b c Dhir A, Kulkarni SK (August 2008). "Possible involvement of sigma-1 receptors in the anti-immobility action of bupropion, a dopamine reuptake inhibitor". Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 22 (4): 387–394. doi:10.1111/j.1472-8206.2008.00605.x. PMID 18705749.

- ^ a b Brimson JM, Brimson S, Chomchoei C, Tencomnao T (October 2020). "Using sigma-ligands as part of a multi-receptor approach to target diseases of the brain". Expert Opin Ther Targets. 24 (10): 1009–1028. doi:10.1080/14728222.2020.1805435. PMID 32746649.

AXS-05 is a combination of dextromethorphan and bupropion and has been shown to have a rapid (within one week) positive effect in patients with depression. Dextromethorphan, as described above as part of Nuedexta, is a σ-1R agonist, an NMDA antagonist, and has an affinity for the serotonin reuptake transporter. Whereas, bupropion is a moderately effective antidepressant when taken alone, thought to act by preventing dopamine and noradrenaline reuptake [230]. Studies in mice have shown that the antidepressant-like effects of bupropion are potentiated by σ-1R agonists, and inhibited by σ-1R antagonists [231]. These findings suggest that the combination of a σ-1R agonist and the dopamine/ noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor will be more effective than either treatment alone.

- ^ Ferris RM, Russell A, Tang FL, Topham PA (1991). "Labeling in vivo of sigma receptors in mouse brain with [ 3 H]-(+)-SKF 10,047: Effects of phencyclidine, (+)- and (−)-N-allylnormetazocine, and other drugs". Drug Development Research. 24 (1): 81–92. doi:10.1002/ddr.430240107. ISSN 0272-4391.

- ^ Pei Y, Asif-Malik A, Canales JJ (2016). "Trace Amines and the Trace Amine-Associated Receptor 1: Pharmacology, Neurochemistry, and Clinical Implications". Front Neurosci. 10: 148. doi:10.3389/fnins.2016.00148. PMC 4820462. PMID 27092049.

- ^ Docherty JR, Alsufyani HA (August 2021). "Pharmacology of Drugs Used as Stimulants". J Clin Pharmacol. 61 Suppl 2: S53–S69. doi:10.1002/jcph.1918. PMID 34396557.

Many stimulants have potency at the rat TAAR1 in the micromolar range but tend to be about 5 to 10 times less potent at the human TAAR1, but bupropion was found to be inactive.87,88

- ^ Simmler LD, Buchy D, Chaboz S, Hoener MC, Liechti ME (April 2016). "In Vitro Characterization of Psychoactive Substances at Rat, Mouse, and Human Trace Amine-Associated Receptor 1". J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 357 (1): 134–144. doi:10.1124/jpet.115.229765. PMID 26791601.

- ^ Gursahani H, Jolas T, Martin M, Cotier S, Hughes S, Macfadden W, et al. (2023). "Preclinical Pharmacology of Solriamfetol: Potential Mechanisms for Wake Promotion". CNS Spectrums. 28 (2): 222. doi:10.1017/S1092852923001396. ISSN 1092-8529.

In vitro functional studies showed agonist activity of solriamfetol at human, mouse, and rat TAAR1 receptors. hTAAR1 EC50 values (10–16 μM) were within the clinically observed therapeutic solriamfetol plasma concentration range and overlapped with the observed DAT/NET inhibitory potencies of solriamfetol in vitro. TAAR1 agonist activity was unique to solriamfetol; neither the WPA modafinil nor the DAT/NET inhibitor bupropion had TAAR1 agonist activity.

- ^ Wainscott DB, Little SP, Yin T, Tu Y, Rocco VP, He JX, et al. (January 2007). "Pharmacologic characterization of the cloned human trace amine-associated receptor1 (TAAR1) and evidence for species differences with the rat TAAR1". J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 320 (1): 475–485. doi:10.1124/jpet.106.112532. PMID 17038507.

- ^ a b Strawbridge R, Izurieta E, Day E, Tee H, Young K, Tong CC, et al. (2023). "Peripheral inflammatory effects of different interventions for treatment-resistant depression: A systematic review". Neuroscience Applied. 2. Elsevier BV: 101014. doi:10.1016/j.nsa.2022.101014. ISSN 2772-4085. S2CID 253283525.

- ^ Hajhashemi V, Khanjani P (2014). "Analgesic and anti-inflammatory activities of bupropion in animal models". Res Pharm Sci. 9 (4): 251–7. PMC 4314873. PMID 25657796.

- ^ Karimollah A, Hemmatpur A, Vahid T (August 2021). "Revisiting bupropion anti-inflammatory action: involvement of the TLR2/TLR4 and JAK2/STAT3". Inflammopharmacology. 29 (4): 1101–1109. doi:10.1007/s10787-021-00829-4. PMID 34218389. S2CID 234883621.

- ^ Yetkin D, Yılmaz İA, Ayaz F (September 2023). "Anti-inflammatory activity of bupropion through immunomodulation of the macrophages". Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch Pharmacol. 396 (9): 2087–2093. doi:10.1007/s00210-023-02462-0. PMID 36928557. S2CID 257583439.

- ^ Chen WC, Lai HC, Su WP, Palani M, Su KP (January 2015). "Bupropion for interferon-alpha-induced depression in patients with hepatitis C viral infection: an open-label study". Psychiatry Investig. 12 (1): 142–5. doi:10.4306/pi.2015.12.1.142. PMC 4310912. PMID 25670957.

- ^ Cámara-Lemarroy CR, Guzmán-de la Garza FJ, Cordero-Pérez P, Alarcón-Galván G, Ibarra-Hernández JM, Muñoz-Espinosa LE, et al. (2013). "Bupropion reduces the inflammatory response and intestinal injury due to ischemia-reperfusion". Transplant Proc. 45 (6): 2502–5. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2013.04.010. PMID 23953570.

- ^ a b Tafseer S, Gupta R, Ahmad R, Jain S, Bhatia MS, Gupta LK (January 2021). "Bupropion monotherapy alters neurotrophic and inflammatory markers in patients of major depressive disorder". Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 200: 173073. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2020.173073. PMID 33186562. S2CID 226292409.

- ^ a b Brustolim D, Ribeiro-dos-Santos R, Kast RE, Altschuler EL, Soares MB (June 2006). "A new chapter opens in anti-inflammatory treatments: the antidepressant bupropion lowers production of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interferon-gamma in mice". Int Immunopharmacol. 6 (6): 903–7. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2005.12.007. PMID 16644475. Archived from the original on 16 October 2023. Retrieved 25 October 2023.

- ^ Kharasch ED, Neiner A, Kraus K, Blood J, Stevens A, Schweiger J, et al. (May 2019). "Bioequivalence and Therapeutic Equivalence of Generic and Brand Bupropion in Adults With Major Depression: A Randomized Clinical Trial". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 105 (5): 1164–1174. doi:10.1002/cpt.1309. PMC 6465131. PMID 30460996.