Tatars

татарлар tatarlar تاتارلار | |

|---|---|

"Tatar" (𐱃𐱃𐰺), written in Old Turkic on an image of the Kul Tigin monument of Orkhon inscriptions, which included one of the first precise transcriptions of the ethnonym. | |

| Total population | |

Total: ~7.3 million[1]

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

Russia

| 5,554,601[9] |

| Ukraine

| 319,377[10] |

| Uzbekistan | ~239,965[11] (Crimean Tatars) |

| Kazakhstan | 208,987[12] |

| Turkey | 500,000–6,900,000[4][5][6][a] |

| Afghanistan | 100,000[13] (estimate) |

| Turkmenistan | 36,655[14] |

| Kyrgyzstan | 28,334[15] |

| Azerbaijan | 25,900[16] |

| Romania | ~20,000[17] |

| United States | 10,000[18] |

| Belarus | 3,000[19] |

| France | 700[20] |

| Switzerland | 1,045+[21] |

| China | 3,556[22] |

| Canada | 56,000[23] (incl. those of mixed ancestries) |

| Poland | 1,916[24] |

| Bulgaria | 5,003[25] |

| Finland | 600–700[26] |

| Japan | 600–2000[27] |

| Australia | 900+[28] |

| Czech Republic | 300+[29] |

| Estonia | 2,000[30] |

| Latvia | 2,800[3] |

| Lithuania | 2,800–3,200[31][32][33] (incl. all of Lipka, Crimean and Volga origins) |

| Iran | 20,000–30,000[34] (Volga Tatars) |

| Languages | |

| Kipchak languages | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Sunni Islam with Eastern Orthodox minority | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Turkic peoples, especially other speakers of Kipchak languages | |

The Tatars[b] (/ˈtɑːtərz/ TAH-tərz),[35] formerly also spelled Tartars,[b] is an umbrella term for different Turkic ethnic groups bearing the name "Tatar" across Eastern Europe and Asia.[36]

Initially, the ethnonym Tatar possibly referred to the Tatar confederation. That confederation was eventually incorporated into the Mongol Empire when Genghis Khan unified the various steppe tribes.[37] Historically, the term Tatars (or Tartars) was applied to anyone originating from the vast Northern and Central Asian landmass then known as Tartary, a term which was also conflated with the Mongol Empire itself. More recently, however, the term has come to refer more narrowly to related ethnic groups who refer to themselves as Tatars or who speak languages that are commonly referred to as Tatar.

The largest group amongst the Tatars by far are the Volga Tatars, native to the Volga-Ural region (Tatarstan and Bashkortostan) of European Russia, who for this reason are often also known as "Tatars" in Russian. They compose 53% of the population in Tatarstan. Their language is known as the Tatar language. As of 2010[update], there were an estimated 5.3 million ethnic Tatars in Russia.

While also speaking languages belonging to different Kipchak sub-groups, genetic studies have shown that the three main groups of Tatars (Volga, Crimean, Siberian) do not have common ancestors and, thus, their formation occurred independently of one another. However, it is possible that all Tatar groups have at least partially the same origin, mainly from the times of the Golden Horde.[38][39]

Many noble families in the Tsardom of Russia and Russian Empire had Tatar origins.[40][41]

Etymology

[edit]

Tatar became a name for populations of the former Golden Horde in Europe, such as those of the former Kazan, Crimean, Astrakhan, Qasim, and Siberian Khanates. The form Tartar has its origins in either Latin or French, coming to Western European languages from Turkish and the Persian language (tātār, "mounted messenger"). From the beginning, the extra r was present in the Western forms and according to the Oxford English Dictionary this was most likely due to an association with Tartarus.[c][42]

The Persian word is first recorded in the 13th century in reference to the hordes of Genghis Khan and is of unknown origin; according to the Oxford English Dictionary it is "said to be" ultimately from tata. The Arabic word for Tatars is تتار. Tatars themselves wrote their name as تاتار or طاطار.

Ochir (2016) states that Siberian Tatars and the Tatars living in the territories between Asia and Europe are of Turkic origin, acquired the appellation Tatar later, and do not possess ancestral connection to the Mongolic Nine Tatars, whose ethnogenesis involved Mongolic people as well as Mongolized Turks who had been ruling over them during the 6–8th centuries.[43] Pow (2019) proposes that Turkic-speaking peoples of Cumania, as a sign of political allegiance, adopted the endonym Tatar of their Mongol conquerors, before ultimately subsuming the latter culturally and linguistically.[44]

Some Turkic peoples living within the Russian Empire were named Tatar, although not all Turkic peoples of Russian Empire were referred to as Tatars (for instance, this name was never used in relation to the Yakuts, Chuvashes, Sarts and some others). Some of these populations used and keep using Tatar as a self-designation, others do not.[45][46][47][48]

- Kipchak groups

- Kipchak–Bulgar branch or "Tatar" in the narrow sense

- Kipchak–Cuman branch

- Crimean Tatars

- Karachays and Balkars: Mountain Tatars

- Kumyks: Daghestan Tatars

- Kipchak–Nogai branch:

- Dobrujan Tatars

- Nogais: Nogai Tatars

- Siberian Tatars

- Siberian branch:

- Oghuz branch

- Azerbaijanis: Caucasus Tatars (also Transcaucasia Tatars or Azerbaijan Tatars)

The term is originally not just an exonym, since the Polovtsians of Golden Horde called themselves Tatar.[49] It is also an endonym to a number of peoples of Siberia and Russian Far East, namely the Khakas people (тадар, tadar).[50]

Languages

[edit]

Eleventh-century Kara-khanid scholar Mahmud al-Kashgari noted that the historical Tatars were bilingual, speaking other Turkic languages besides their own.[51]

The modern Tatar language, together with the Bashkir language, forms the Kypchak-Volga-Ural group within the Kipchak languages (also known as Northwestern Turkic).

There are two Tatar dialects—Central and Western.[52] The Western dialect (Misher) is spoken mostly by Mishärs, the Central dialect is spoken by Kazan and Astrakhan Tatars. Both dialects have subdialects. Central Tatar furnishes the base of literary Tatar.

The Siberian Tatar language is independent of Volga–Ural Tatar. The dialects are quite remote from Standard Tatar and from each other, often preventing mutual comprehension. The claim that Siberian Tatar is part of the modern Tatar language is typically supported by linguists in Kazan and denounced by Siberian Tatars.[citation needed]

Crimean Tatar[e] is the indigenous language of the Crimean Tatar people. Because of its common name, Crimean Tatar is sometimes mistakenly seen in Russia as a dialect of Kazan Tatar. Although these languages are related (as both are Turkic), the Kypchak languages closest to Crimean Tatar are (as mentioned above) Kumyk and Karachay-Balkar, not Kazan Tatar. Still, there exists an opinion (E. R. Tenishev), according to which the Kazan Tatar language is included in the same Kipchak-Cuman group as Crimean Tatar.[53]

Contemporary groups and nations

[edit]The largest Tatar populations are the Volga Tatars, native to the Idel-Ural (Volga-Ural) region of European Russia, and the Crimean Tatars of Crimea. Smaller groups of Lipka Tatars and Astrakhan Tatars also live in Europe and the Siberian Tatars in Asia.

Volga Tatars

[edit]

In the 7th century AD, the Volga Bulgars settled on the territory of the Volga-Kama region, where Finno-Ugrians lived compactly at that time. Bulgars inhabited part of the modern territory of Tatarstan, Udmurtia, Ulyanovsk region, Samara region and Chuvashia. After the invasion of Batu Khan in 1223–1236, the Golden Horde annexed Volga Bulgaria. Most of the population of the Bulgars survived and crossed to the right bank of the Volga, displacing the mountain Mari (cheremis) from the inhabited territories to the meadow side. Sources of Russian chronicles[citation needed] report: "Tatares took the whole Bulgarian land captive and killed part of it" After a while, Tatars from all the outskirts of the Golden Horde began to arrive in the Kazan Khanate, and consisted mainly of Kipchak peoples: Nogais and Crimean Tatars.

Kazan was built by the Perekop fugitives from Taurida during the reign of Vasily Vasilyevich in Moscow. Vasily Ivanovich forced her to take tsars from him for herself. And then, when she was indignant, he embarrassed her with the hardships of a dangerous war, but he did not conquer her. But in 7061 (1552), his son Ivan IV took the city of Kazan after a six-month siege together with the Cheremis. However, in the form of a reward for the offense, he subdued neighboring Bulgaria, which he could not stand for frequent rebellions. — The journey to Muscovy of Baron Augustine Mayerberg and Horace Wilhelm Calvucci, ambassadors of the August Roman Emperor Leopold to the Tsar and Grand Duke Alexei Mikhailovich in 1661, described by Baron Mayerberg himself

Kazan Tatars are descendants of the Tatars of the Kazan Kingdom of the Kipchak Horde. — "Alphabetical list of peoples living in the Russian Empire in 1895"[1]

Kazan Tatars got their name from the main city of Kazan—and it is so called from the Tatar word Kazan, the cauldron, which was omitted by the servant of the founder of this city, Khan Altyn Bek, not on purpose, when he scooped water for his master to wash, in the river now called Kazanka. In other respects, according to their own legends, they were not of a special tribe, but descended from the fighters who remained here [in Kazan] on the settlement of different generations and from foreigners attracted to Kazan, but especially Nogai Tatars, who all through their union into a single society formed a special people.

— Carl Wilhelm Müller. "Description of all the peoples living in the Russian state,.." Part Two. About the peoples of the Tatar tribe. S-P, 1776, Translated from German.[38]

— Johann Gottlieb Georgi. Description of all the peoples living in the Russian state : their everyday rituals, customs, clothes, dwellings, exercises, amusements, faiths and other memorabilia. Part 2 : About the peoples of the Tatar tribe and other undecided origin of the Northern Siberian. — 1799. page 8[39]

Also in Kazan there is a famous "Kaban Lake" similar to the name of the "Kuban River", which translates from Nogai as "overflowing".

The main now central Bauman Street that leads to the Kremlin is one of the oldest streets in Kazan. In the era of the Kazan Khanate, it was called the Nogai district. Nogai daruga is a conditional territory, the possessions of which are controlled by the Nogai Horde, they were run by foremen beki:

- Alibai Murzagulov, in 1773 the foreman of the Nogaiskaya daruga (administrative territory - district)

- Kinzya Arslanov foreman of the Bushmas-Kipchak parish of the Nogaiskaya daruga (administrative territory)

- Yamansary Yapparov foreman of the Suun-Kypsak parish of the Nogaiskaya daruga (administrative territory)

The Tatar Queen Syuyumbike, who was the daughter of the Nogai biya, also testifies to the Nogai roots of the Kazan Tatars. And this is also confirmed by the Khans of the Kazan Khanate:

- Ulu-Muhammad Khan, son of Ichkile Hasan-oglan (1438–1445), former khan of the Golden Horde.

- Mamuk (Tyumen tatar) Khan (1496–1497).

- Shah-Ali Khan, son of Kasimov tatar Sheikh-Auliyar Sultan (1519–1521, 1546, 1551–1552).

- Sahib-Giray Khan, son of Crimean tatar Khan Mengli Giray (1521–1524, 1524–1531, 1536–1546, 1546–1549).

- Utyamysh-Giray Nogai tatar Khan, son of Safa-Giray Khan (1549–1551).

- Yadygar-Muhammad Khan, son of Kasimov tatar Khan of Astrakhan (1552).

- Ali-Akram Khan (Nogai dynasty) (1553–1556).

The large coat of arms of Tsar Ivan IV the Terrible testifies that the Tatars of the Kazan Khanate and the Bulgars of the Volga Bulgarian land are different peoples and territories with different coats of arms.

Forming

The formation of the Kazan Tatars occurred only in the Golden Horde in the 14th - first half of the 15th century. from the Central Asian Turkic-Tatar tribes that arrived with the Mongols and appeared in the Lower Volga region in the 11th century. Kipchaks (Polovtsians). There were only minor groups of Kipchak tribes on the Bulgarian and Cheremis land, and there were very few of them on the territory of the future Kazan Khanate. But during the events of 1438–1445, associated with the formation of the Kazan Khanate, together with Khan Uluk-Muhammad, about 40 thousand Tatars arrived here at once. Subsequently, Tatars from Astrakhan, Azov, Crimea, Akhtubinsk and other places moved to the Kazan Khanate. The Arab historian Al-Omari (Shihabuddin al-Umari) wrote that, having joined the Golden Horde, the Cumans moved to the position of subjects. The Tatar-Mongols who settled on the territory of the Polovtsian steppe gradually mixed with the Polovtsians. Al-Omari concludes that after several generations, the Tatars began to look like Polovtsy: "as if from the same (with them) kind," because they began to live on their lands.

Finally in the end of the 19th century; although the name Nogailars persisted in some places; the majority identified themselves simply as the Muslims[citation needed]) and the language of the Kipchaks; on the other hand, the invaders eventually converted to Sunni Islam (c. 14th century). As the Golden Horde disintegrated in the 15th century, the area became the territory of the Kazan khanate, which Russia ultimately conquered in the 16th century.

Some Volga Tatars speak different dialects of the Tatar language. Accordingly, they form distinct groups such as the Mişär group and the Qasim group:

- Mişär-Tatars (or Mishars) are a group of Tatars speaking a Mishar dialect of the Tatar language. They live in the Chelyabinsk, Tambov, Penza, Ryazan and Nizhegorodskaya oblasts of Russia and in Bashkortostan and Mordovia. They live on the right bank of the Volga River, in Tatarstan.

- The Western Tatars have their capital in the town of Qasím (Kasimov, Russian: Касимов) in Ryazan Oblast, with a Tatar population of 1100.[citation needed]

A minority of Christianized Volga Tatars are known as Keräşens.

The Volga Tatars used the Turkic Old Tatar language for their literature between the 15th and 19th centuries. It was written in the İske imlâ variant of the Arabic script, but actual spelling varied regionally. The older literary language included many Arabic and Persian loanwords. However, the modern literary language (generally written using a Cyrillic alphabet), often has Russian- and other European-derived words instead.

Outside of Tatarstan, urban Tatars usually speak Russian as their first language (in cities such as Moscow, Saint Petersburg, Nizhniy Novgorod, Tashkent, Almaty, and in cities of the Ural region and western Siberia) and other languages in a worldwide diaspora.

In the 1910s the Volga Tatars numbered about half a million in the Kazan Governorate in Tatarstan, their historical homeland, about 400,000 in each of the governments of Ufa, 100,000 in Samara and Simbirsk, and about 30,000 in Vyatka, Saratov, Tambov, Penza, Nizhny Novgorod, Perm and Orenburg. An additional 15,000 had migrated to Ryazan or were settled as prisoners in the 16th and 17th centuries in Lithuania (Vilnius, Grodno and Podolia). An additional 2,000 resided in St. Petersburg.[37]

Most Kazan Tatars practice Islam. The Kazan Tatars speak Kazan (normal) Tatar language, with a substantial amount of Russian and Arabic loanwords.

Before 1917, polygamy was practiced[54][citation needed] only by the wealthier classes and was a waning institution.[37]

Astrakhan Tatars

[edit]The Astrakhan Tatars (around 80,000) are a group of Tatars, descendants of the Astrakhan Khanate's population, who live mostly in Astrakhan Oblast. In the Russian census of 2010 most Astrakhan Tatars declared themselves simply as "Tatars" and few declared themselves as "Astrakhan Tatars". Many Volga Tatars live in Astrakhan Oblast, and differences between the two groups have been disappearing.[citation needed]

Lipka Tatars

[edit]

The Lipka Tatars are a group of Turkic-speaking Tatars who originally settled in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania at the beginning of the 14th century. The first settlers tried to preserve their shamanistic religion and sought asylum amongst the non-Christian Lithuanians.[55] Towards the end of the 14th century Grand Duke Vytautas the Great of Lithuania (ruled 1392–1430) invited another wave of Tatars—Muslims, this time—into the Grand Duchy. These Tatars first settled in Lithuania proper around Vilnius, Trakai, Hrodna and Kaunas[55] and spread to other parts of the Grand Duchy that later became part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1569. These areas comprise parts of present-day Lithuania, Belarus and Poland. From the very beginning of their settlement in Lithuania they were known as the Lipka Tatars.

From the 13th to 17th centuries various groups of Tatars settled and/or found refuge within the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. The Grand Dukes of Lithuania especially promoted the migrations because of the Tatars' reputation as skilled warriors. The Tatar settlers were all granted szlachta (nobility) status, a tradition that survived until the end of the Commonwealth in the late 18th century. Such migrants included the Lipka Tatars (13th–14th centuries) as well as Crimean and Nogay Tatars (15th–16th centuries), all of which were notable in Polish military history, as well as Volga Tatars (16th–17th centuries). They all mostly settled in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

Various estimates of the Tatars in the Commonwealth in the 17th century place their numbers at about 15,000 persons and 60 villages with mosques. Numerous royal privileges, as well as internal autonomy granted by the monarchs, allowed the Tatars to preserve their religion, traditions, and culture over the centuries. The Tatars were allowed to intermarry with Christians,a practice uncommon in Europe at the time. The May Constitution of 1791 gave the Tatars representation in the Polish Sejm (parliament).

Although by the 18th century the Tatars had adopted the local language, the Islamic religion and many Tatar traditions (e.g. the sacrifice of bulls in their mosques during the main religious festivals) survived. This led to the formation of a distinctive Muslim culture, in which the elements of Muslim orthodoxy mixed with religious tolerance formed a relatively liberal society. For instance, the women in Lipka Tatar society traditionally had the same rights and status as men, and could attend non-segregated schools.

About 5,500 Tatars lived within the inter-war boundaries of Poland (1920–1939), and a Tatar cavalry unit had fought for the country's independence. The Tatars had preserved their cultural identity and sustained a number of Tatar organisations, including Tatar archives and a museum in Vilnius.

The Tatars suffered serious losses during World War II and furthermore, after the border change in 1945, a large part of them found themselves in the Soviet Union. It is estimated that about 3,000 Tatars live in present-day Poland, of which about 500 declared Tatar (rather than Polish) nationality in the 2002 census.[citation needed] There are two Tatar villages (Bohoniki and Kruszyniany) in the north-east of present-day Poland, as well as urban Tatar communities in Warsaw, Gdańsk, Białystok, and Gorzów Wielkopolski. Tatars in Poland sometimes have a Muslim surname with a Polish ending: Ryzwanowicz; other surnames adopted by more assimilated Tatars are Tatara or Tataranowicz or Taterczyński, which literally mean "son of a Tatar".

The Tatars played a relatively prominent role for such a small community in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth military as well as in Polish and Lithuanian political and intellectual life.[citation needed] In modern-day Poland, their presence is also widely known, due in part to their noticeable role in the historical novels of Henryk Sienkiewicz (1846–1916), which are universally recognized in Poland. A number of Polish intellectual figures have also been Tatars, e.g. the prominent historian Jerzy Łojek.

A small community of Polish-speaking Tatars settled in Brooklyn, New York City, in the early 20th century. They established a mosque that remained in use as of 2017[update].[56]

Crimean Tatars

[edit]

Crimean Tatars are an indigenous people of Crimea. Their formation occurred during the 13th–17th centuries, primarily from Cumans that appeared in Crimea in the 10th century, with strong contributions from all the peoples who ever inhabited Crimea (Greeks, Scythians, and Goths).[57]

At the beginning of the 13th century, Crimea, where the majority of the population was already composed of a Turkic people—Cumans, became a part of the Golden Horde. The Crimean Tatars mostly adopted Islam in the 14th century and thereafter Crimea became one of the centers of Islamic civilization in Eastern Europe. In the same century, trends towards separatism appeared in the Crimean Ulus of the Golden Horde. De facto independence of Crimea from the Golden Horde may be counted since the beginning of princess (khanum) Canike's, the daughter of the powerful Khan of the Golden Horde Tokhtamysh and the wife of the founder of the Nogai Horde Edigey, reign in the peninsula. During her reign she strongly supported Hacı Giray in the struggle for the Crimean throne until her death in 1437. Following the death of Сanike, the situation of Hacı Giray in Crimea weakened and he was forced to leave Crimea for Lithuania.[58]

In 1441, an embassy from the representatives of several strongest clans of Crimea, including the Golden Horde clans Shırın and Barın and the Cumanic clan—Kıpçak, went to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania to invite Hacı Giray to rule in Crimea. He became the founder of the Giray dynasty, which ruled until the annexation of the Crimean Khanate by Russia in 1783.[59] Hacı I Giray was a Jochid descendant of Genghis Khan and of his grandson Batu Khan of the Golden Horde. During the reign of Meñli I Giray, Hacı's son, the army of the Great Horde that still existed then invaded Crimea from the north, Crimean Khan won the general battle, overtaking the army of the Horde Khan in Takht-Lia, where he was killed, the Horde ceased to exist, and the Crimean Khan became the Great Khan and the successor of this state.[59][60] Since then, the Crimean Khanate was among the strongest powers in Eastern Europe until the beginning of the 18th century.[61] The Khanate officially operated as a vassal state of the Ottoman Empire, with great autonomy after 1580,[62] because of being a Muslim state, the Crimean Khanate just could not be separate from the Ottoman caliphate, and therefore the Crimean khans had to recognize the Ottoman caliph as the supreme ruler, in fact, the viceroy of God on earth. At the same time, the Nogai hordes, not having their own khan, were vassals of the Crimean one, the Tsardom of Russia and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth[63][64] paid annual tribute to the khan (until 1700[65] and 1699, respectively). In 1711, when Peter I of Russia went on a campaign with all his troops (80,000) to gain access to the Black Sea, he was surrounded by the army of the Crimean Khan Devlet II Giray, finding himself in a hopeless situation. And only the betrayal of the Ottoman vizier Baltacı Mehmet Pasha allowed Peter to get out of the encirclement of the Crimean Tatars.[66] When Devlet II Giray protested against the vizier's decision,[f] his response was: "You might know your Tatar affairs. The affairs of the Sublime Porte are entrusted to me. You do not have the right to interfere in them."[67] Treaty of the Pruth was signed, and 10 years later, Russia declared itself an empire. In 1736, the Crimean Khan Qaplan I Giray was summoned by the Turkish Sultan Ahmed III to Persia. Understanding that Russia could take advantage of the lack of troops in Crimea, Qaplan Giray wrote to the Sultan to think twice, but the Sultan was persistent. As it was expected by Qaplan Giray, in 1736 the Russian army invaded Crimea, led by Münnich, devastated the peninsula, killed civilians and destroyed all major cities, occupied the capital, Bakhchisaray, and burnt the Khan's palace with all the archives and documents, and then left Crimea because of the epidemic that had begun in it. One year later the same was done by another Russian general—Peter Lacy.[59][68] Since then, the Crimean Khanate had not been able to recover, and its slow decline began. The Russo-Turkish War of 1768 to 1774 resulted in the defeat of the Ottomans by the Russians, and according to the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774) signed after the war, Crimea became independent and the Ottomans renounced their political right to protect the Crimean Khanate. After a period of political unrest in Crimea, Imperial Russia violated the treaty and annexed the Crimean Khanate in 1783.

Due to the oppression by the Russian administration, the Crimean Tatars were forced to immigrate to the Ottoman Empire. In total, from 1783 till the beginning of the 20th century, at least 800 thousand Tatars left Crimea. In 1917, the Crimean Tatars, in an effort to recreate their statehood, announced the Crimean People's Republic—the first democratic republic in the Muslim world, where all peoples were equal in rights. The head of the republic was the young politician Noman Çelebicihan. However, a few months later the Bolsheviks captured Crimea, and Çelebicihan was killed without trial and thrown into the Black Sea. Soon in Crimea, Soviet power was established.

Through the fault of the Soviet government, which exported bread from Crimea to other regions of the country, in 1921–1922, at least 76,000 Crimean Tatars died of starvation,[69] which became a disaster for such a small nation. In 1928, the first wave of repression against the Crimean Tatar intelligentsia was launched, in particular, the head of the Crimean ASSR, Veli İbraimov, was executed in a fabricated case. In 1938, the second wave of repression against the Crimean Tatar intelligentsia was started, during which many Crimean Tatar writers, scientists, poets, politicians, teachers were killed (Asan Sabri Ayvazov, Usein Bodaninsky, Seitdzhelil Hattatov, Ilyas Tarhan and many others).[70][71][72][73] In May 1944, the USSR State Defense Committee ordered the total deportation of all the Crimean Tatars from Crimea. The deportees were transported in cattle trains to Central Asia, primarily to Uzbekistan. During the deportation and in the first years of being in exile, 46% of Crimean Tatars died.[74] In 1956, Khrushchev exposed Stalin's cult of personality and allowed deported peoples to return to their homeland. The exception was the Crimean Tatars. Since then, a powerful national movement of the Crimean Tatars, supported abroad and by Soviet dissidents, began, and in 1989 the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union was made to condemn the deportation of Crimean Tatars from their motherland as inhumane and lawless. Crimean Tatars began to return to their homeland. Today, Crimean Tatars constitute approximately 12% of the population of Crimea. There is a large diaspora in Turkey and Uzbekistan, but most (especially in Turkey) of them do not consider themselves Crimean Tatars.[4] Still, there remains a diaspora in Dobruja, where most of the Tatars keep identifying themselves as Crimean Tatars.

Nowadays, the Crimean Tatars comprise three sub-ethnic groups:

- the Tats (not to be confused with Tat people, living in the Caucasus region) who used to inhabit the Crimean Mountains before 1944

- the Yalıboylu who lived on the southern coast of the peninsula

- the Noğays who used to live in the northern part of the Crimea

Crimean Tatars in Dobruja

[edit]Some Crimean Tatars have lived in the territory of today's Romania and Bulgaria since the 13th century. In Romania, according to the 2002 census, 24,000 people declared their ethnicity as Tatar, most of them being Crimean Tatars living in Constanța County in the region of Dobruja. Most of the Crimean Tatars, living in Romania and Bulgaria nowadays, left the Crimean peninsula for Dobruja after the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Empire.

Dobrujan Tatars have been present in Romania since the 13th century.[75] The Tatars first reached the mouths of the Danube in the mid-13th century at the height of the power of the Golden Horde. In the 14th and 15th centuries the Ottoman Empire colonized Dobruja with Nogais from Budjak. Between 1593 and 1595 Tatars from Nogai and Budjak were also settled to Dobruja. Toward the end of the 16th century, about 30,000 Nogai Tatars from the Budjak were brought to Dobruja.[76] After the Russian annexation of Crimea in 1783 Crimean Tatars began emigrating to the Ottoman coastal provinces of Dobruja (today divided between Romania and Bulgaria). Once in Dobruja most settled in the areas surrounding Mecidiye, Babadag, Köstence, Tulça, Silistre, Beştepe, or Varna and went on to create villages named in honor of their abandoned homeland such as Şirin, Yayla, Akmecit, Yalta, Kefe or Beybucak. Tatars together with Albanians served as gendarmes, who were held in high esteem by the Ottomans and received special tax privileges. The Ottomans additionally accorded a certain degree of autonomy for the Tatars who were allowed governance by their own kaymakam, Khan Mirza. The Giray dynasty (1427–1878) multiplied in Dobruja and maintained their respected position. A Dobrujan Tatar, Kara Hussein, was responsible for the destruction of the Janissary corps on orders from Sultan Mahmut II.

Siberian Tatars

[edit]

The Siberian Tatars occupy three distinct regions:

They originated in the agglomerations of various indigenous North Asian groups which, in the region north of the Altay, reached some degree of culture between the 4th and 5th centuries, but were subdued and enslaved by the Mongols.[37] The 2010 census recorded 6,779 Siberian Tatars in Russia. According to the 2002 census there are 500,000 Tatars in Siberia, but 400,000 of them are Volga Tatars who settled in Siberia during periods of colonization.[77]

Population of Tatars, 1926–2021

[edit]| Census | 1926 | 1939 | 1959 | 1970 | 1979 | 1989 | 2002 | 2010 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 3,926,053 | 3,682,956 | 4,074,253 | 4,577,061 | 5,055,757 | 5,522,096 | 5,554,601 | 5,310,649 | 4,713,669 |

| Percentage | 3.89% | 3.40% | 3.47% | 3.52% | 3.68% | 3.75% | 3.87% | 3.87% | 3.61% |

Gallery

[edit]- Flags

- Flags

-

Flag of the Nogai Horde

-

Flag of the Crimean Tatars

-

Flag of Tatarstan

-

Flag of the Kazan Khanate

-

Flag of the Crimean Khanate[78]

-

Golden Horde flag

-

Tartary flag

- Pictures

- Pictures

-

Crimean Tatar men and boys

-

Crimean Tatar women, early 1900s

- Paintings

- Paintings

-

Tatar elder and his horse

-

Tatar woman

-

Crimean Tatar woman

-

Tatar woman

-

Crimean Tatar woman

-

Tatar woman

-

Crimean Tatar shepherd-boy

-

Lithuanian Tatars of Napoleonic army

-

Crimean Tatar family, 1840

-

Crimean Tatar girl from Kapsikhor

-

Daghestani Tatar elder

-

Tatar Queen Söyembikä and

her son, Ötemish Giray Khan -

Tatar family in 1843

-

Dance of Crimean Tatars. Crimea, 1856.

-

Crimean Tatar family and a mullah

-

Crimean Tatar princess in 1682

-

Tatar child ca. 19th century

-

Tatars' raid on Moscow

-

Recovery of Tatar captives

-

Crimean Tatar squadrone of the Russian empire

-

Tatar costumes

-

Crimean Tatar elder inviting guests

-

Tatar horsemen

-

Crimean Tatar's national dance

-

Tatars in the vanguard of the Ottoman army

-

Kazan Tatars 1862

- Language

- Language

-

Quran of the Tatars

-

Cover page of Tatar Yana imla book, printed with Separated Tatar language in Arabic script in 1924

-

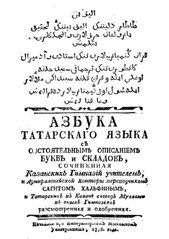

A Tatar alphabet book printed in 1778. Arabic script is used, Cyrillic text is in Russian. Хальфин, Сагит. Азбука татарского языка. — М., 1778. — 52 с.

See also

[edit]- List of Tatars

- Cossacks

- Lists of battles of the Mongol invasion of Europe

- Tatarophobia

- Tatar name

- Uhlan

- Serving Tatars

Notes

[edit]- ^ In Turkey, the census does not indicate the nationality, because all residents of Turkey are considered Turks, so it is impossible to name at least the approximate number of Turkish citizens, considering themselves as Crimean Tatars.

- ^ a b Often spelled Tartars in English to specify the pronunciation /ˈtɑː-/ and prevent misinterpretation as /teɪ-/.

Tatar: татарлар, romanized: tatarlar, تاتارلر; Crimean Tatar: tatarlar; Old Turkic: 𐱃𐱃𐰺, romanized: Tatar) - ^ citing a letter to St Louis of Frances dated 1270 which makes the connection explicit, "In the present danger of the Tartars either we shall push them back into the Tartarus whence they are come, or they will bring us all into heaven."[42]

- ^ The name originating from the name of Spruce-fir Taiga forests in Russian language: черневая тайга

- ^ also rarely called Crimean language or even more rarely Crimean Turkic

- ^ He was claiming: "Such a strong and merciless enemy as Moscow, falling on its feet, fell into our hands. This is such a convenient case when, if we wish so, we can capture Russia from one side to the other, since I know for sure that the whole the strength of the Russian army is this army. Our task now is to pat the Russian army so that it cannot move anywhere from this place, and we will get to Moscow and bring the matter to the point that the Russian Tsar would be appointed by our padishah."[67]

References

[edit]- ^ "Putin's Power Play? Tatarstan Activists Say Loss Of 'President' Title Would Be An Existential Blow". Radio Free Europe. 19 October 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- ^ "Tatars facts, information, pictures – Encyclopedia.com articles about Tatars". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ^ a b "Tatar". Joshua Project. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- ^ a b c Henryk Jankowski. Crimean Tatars and Noghais in Turkey // a slightly edited version of the paper with the same title that appeared in Türk Dilleri Arastirmalari [Studies on the Turkic Languages] 10 (2000): 113–131, distributed by Sanat Kitabevi, Ankara, Turkey. A Polish version of this paper was published in Rocznik Tatarów Polskich (Journal of Polish Tatars), vol. 6, 2000, 118–126.

- ^ a b Мусафирова, О.. "Мустафа, сынок, прошу тебя — прекрати…". Novaya Gazeta. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- ^ a b Пашаев, Осман (18 November 2002). "В Турции проживают до 6 миллионов потомков крымских татар". podrobnosti. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ^ "Afghanistan Recognizes Long Forgotten Ethnic Tatar Community". www.rferl.org. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ^ "کنگره جهانی تاتارها: یک هزار دانشجوی تاتار افغانستان به چین و هند میروند". افغانستان اینترنشنال (in Persian). 13 December 2023. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ^ "Population Data". singapore.mid.ru. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "About number and composition population of Ukraine by data All-Ukrainian census of the population 2001". Ukraine Census 2001. State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- ^ "Крымские татары". Great Russian Encyclopedia (in Russian). Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- ^ "Численность населения Республики Казахстан по отдельным этносам на начало 2021 года" [The population of the Republic of Kazakhstan by individual ethnic groups at the beginning of 2021]. stat.gov.kz. Archived from the original on 2 May 2021. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ^ "Afghanistan Recognizes Long Forgotten Ethnic Tatar Community". Radiofreeeurope/Radioliberty. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

Community leaders estimate there are up to 100,000 ethnic Tatars in Afghanistan.

- ^ Asgabat.net-городской социально-информационный портал :Итоги всеобщей переписи населения Туркменистана по национальному составу в 1995 году. Archived 13 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "National composition of the population" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 November 2013. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 30 November 2012. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Recensamant Romania 2002". Agentia Nationala pentru Intreprinderi Mici si Mijlocii (in Romanian). 2002. Archived from the original on 13 May 2007. Retrieved 5 August 2007.

- ^ "Tatar in United States". Joshua Project. 23 March 2021. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ "Tatars In Belarus". Radio Free Europe. 12 August 2010. Retrieved 31 October 2021.

- ^ Рушан, Лукманов (16 May 2018). "Vasil Shaykhraziev met with the Tatars of France | Всемирный конгресс татар". Retrieved 31 October 2021.

- ^ "Rustam Minnikhanov meets representatives of the Tatar Diaspora in Switzerland". President of Republic of Tatarstan. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- ^ "Regional Autonomy for Minority Peoples". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China. Archived from the original on 17 October 2006. Retrieved 6 September 2006.

- ^ "Census Profile, 2016 Census – Canada [Country] and Canada [Country]". 8 February 2017. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- ^ "Ludność. Stan i struktura demograficzno-społeczna – NSP 2011" (PDF) (in Polish). Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ^ "National Statistical Institute". www.nsi.bg. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- ^ "Suomen tataareja johtaa pankkiuran tehnyt ekonomisti Gölten Bedretdin, jonka mielestä uskonnon pitää olla hyvän puolella". Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ "Статьи на исторические темы". www.hrono.ru. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 16 August 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Президент РТ". Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- ^ "RL0428: RAHVASTIK RAHVUSE, SOO JA ELUKOHA JÄRGI, 31. DETSEMBER 2011". stat.ee. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ^ "Адас Якубаускас: Я всегда говорю крымским татарам не выезжайте, оккупация не вечна". espreso.tv. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ "Как крымские татары оказались в Литве 600 лет назад? | Новости и аналитика : Украина и мир : EtCetera". Archived from the original on 12 August 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ Национальный состав населения Литвы. Перепись 2011.

- ^ Paul Goble (20 June 2016). "Volga Tatars in Iran Being Turkmenified". Jamestown. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ Tatar in the Collins English Dictionary

- ^ "Tatar – people". Archived from the original on 30 July 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- ^ a b c d One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Kropotkin, Peter; Eliot, Charles (1911). "Tatars". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 448–449.

- ^ a b "Татары Евразии: своеобразие генофондов крымских, поволжских и сибирских татар". Вестник Московского Университета. Серия 23. Антропология (3): 75–85. 20 January 2024.

- ^ a b "Внешний вид (фото), Оглавление (Содержание) книги Еникеева Г.Р. "По следам чёрной легенды"".

- ^ Thomas Riha, Readings in Russian Civilization, Volume 1: Russia Before Peter the Great, 900–1700, University of Chicago Press (2009), p. 186

- ^ Baskakov: Русские фамилии тюркского происхождения (Russian surnames of Turkic origin) (1979)

- ^ a b Wedgwood, Hensleigh (1855). "On False Etymologies". Transactions of the Philological Society (6): 72.

- ^ Очир А. (2016). Монгольские этнонимы: вопросы происхождения и этнического состава монгольских народов (PDF). Элиста: КИГИ РАН. ISBN 978-5-903833-93-1. quote (p. 160-161): "Ныне татарами называют этнические группы, имеющие монгольское и тюркское происхождение. Из них так называемые «девять татар» приняли участие в этнокультурном развитии монголов. Татары эти, как племя, сформировались, видимо, в период существования на территории Монголии Тюркского каганата (VI–VIII вв.); помимо монгольского компонента, в процессе этногенеза приняли участие и тюркские, о чем свидетельствует этнический состав татар. В этот период монголами управляли тюрки, которые со временем омонголились. [...] Что же касается сибирских татар и татар, проживающих на территории между Азией и Европой, то они являются выходцами из тюрок. Название татар они получили позднее и не имеют родовой связи с монгольскими («девятью татарами». — А.О.) татарами."

- ^ Pow, Stephen (2019). "'Nationes que se Tartaros appellant': An Exploration of the Historical Problem of the Usage of the Ethnonyms Tatar and Mongol in Medieval Sources"". Golden Horde Review. 7 (3): 545–567. doi:10.22378/2313-6197.2019-7-3.545-567. Archived from the original on 20 July 2021. quote (p 563): "Regarding the Volga Tatar people of today, it appears they took on the endonym of their Mongol conquerors when they overran the Dasht-i-Kipchak. It was preserved as the prevailing ethnonym in the subsequent synthesis of the Mongols and their more numerous Turkic subjects who ultimately subsumed their conquerors culturally and linguistically as al-Umari noted by the fourteenth century [32, p. 141]. I argue that the name 'Tatar' was adopted by the Turkic peoples in the region as a sign of having joined the Tatar conquerors – a practice which Friar Julian reported in the 1230s as the conquest unfolded. The name stands as a testament to the survivability and adaptability of both peoples and ethnonyms. It became, as Sh. Marjani stated, their 'proud Tatar name.'"

- ^ Willem Floor (2015) [2007]. Travels through Northern Persia, 1770-1774 / by Samuel Gottlieb Gmelin; translated and annotated by Willem Floor. Mage Publishers. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-933823-15-7.

This en contains too many or overly lengthy quotations. (October 2024)

This en contains too many or overly lengthy quotations. (October 2024) - ^ George A. Bournoutian (2021). From the Kur to the Aras. A Military History of Russia's Move into the South Caucasus and the First Russo-Iranian War, 1801–1813. Iran Studies, vol. 22. Brill. p. 18. ISBN 978-90-04-44516-1.

This en contains too many or overly lengthy quotations. (October 2024)

This en contains too many or overly lengthy quotations. (October 2024) - ^ «Алфавитный список народов, обитающих в Российской Империи» Archived 2012-02-05 at the Wayback Machine Демоскоп Weekly

- ^ Татары (in Russian). Энциклопедия «Вокруг света». Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- ^ Гаркавец А. Н. Кыпчакские языки. — Алма-Ата: Наука, 1987. — С. 18.

- ^ Ушницкий В. В. Средневековые народы Центральной Азии (вопросы происхождения и этнической истории тюрко-монгольских племен). — Казань: Изд-во «Фэн» АН РТ, 2009. — С. 4. — 116 с. — ISBN 978-5-9690-0112-1

- ^ Maħmūd al-Kašğari. "Dīwān Luğāt al-Turk". Edited & translated by Robert Dankoff in collaboration with James Kelly. In Sources of Oriental Languages and Literature. Part I. (1982). pp. 82–83

- ^ Akhatov G. "Tatar dialectology". Kazan, 1984. (Tatar language)

- ^ Сравнительно-историческая грамматика тюркских языков. Региональные реконструкции/Отв. ред. Э.Р. Тенишев. – М. Наука. 2002. – 767 с. стр. 732, 736–737

- ^ "westmifflinmoritz.com" (PDF). www.westmifflinmoritz.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2022. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ a b "Lietuvos totoriai ir jų šventoji knyga – Koranas". Archived from the original on 29 October 2007.

- ^ Amid Tatar Renaissance In Europe, An American Mosque Turns To Its Roots – "A Lipka Tatar—a Muslim ethnic group native to the Baltic region—Jakub Szynkiewicz was selected to be Poland's first mufti in 1925, around the time that his community's U.S. diaspora was moving into the very mosque in Brooklyn where his portrait still hangs."

- ^ "История этногенеза крымских татар | Ана юрт". ana-yurt.com. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- ^ Gertsen, Mogarychev Крепость драгоценностей. Кырк-Ор. Чуфут-кале. Archived 29 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine, 1993, pp. 58–64. ISBN 5-7780-0216-5.

- ^ a b c Gayvoronsky, 2007

- ^ Vosgrin, 1992. ISBN 5-244-00641-X.

- ^ Halil İnalcik, 1942 [page needed]

- ^ Great Russian Encyclopedia: Верховная власть принадлежала хану – представителю династии Гиреев, который являлся вассалом тур. султана (официально закреплено в 1580-х гг., когда имя султана стало произноситься перед именем хана во время пятничной молитвы, что в мусульм. мире служило признаком вассалитета) Archived 6 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kochegarov (2008), p. 230

- ^ J. Tyszkiewicz. Tatarzy na Litwie i w Polsce. Studia z dziejow XIII-XVIII w. Warszawa, 1989. p. 167

- ^ Davies (2007), p. 187; Torke (1997), p. 110

- ^ Ahmad III, H. Bowen, The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Vol. I, ed. H.A.R. Gibb, J.H. Kramers, E. Levi-Provencal and J. Shacht (E.J.Brill, 1986), 269.

- ^ a b Halim Giray, 1822 (in Russian)

- ^ Tucker, Spencer C. (2010). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East, Vol. II. ABC-CLIO. p. 732

- ^ Zarubin: Без победителей: из истории Гражданской войны в Крыму, 2008, p. 704

- ^ Расстрел 17 апреля 1938 года. RFEL

- ^ Zmerzly: Политические репрессии среди крымскотатарских преподавателей Крымского государственного университета им. Фрунзе

- ^ Abibullayeva Крымскотатарская интеллигенция – жертва политических репрессий 1920–ых – 1930–ых

- ^ Hayali: Крымские татары в репрессивно-карательной политике в Крымской АССР

- ^ Human Rights Watch, 1991, p. 34

- ^ Klaus Roth, Asker Kartarı, (2017), Cultures of Crisis in Southeast Europe: Part 2: Crises Related to Natural Disasters, to Spaces and Places, and to Identities (19) (Ethnologia Balkanica), p. 223

- ^ Robert Stănciugel and Liliana Monica Bălaşa, Dobrogea în Secolele VII–XIX. Evoluţie istorică, Bucharest, 2005, p.147

- ^ Siberian Tatars Archived 27 February 2002 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Pierre Duval: Le monde ou La géographie universelle. (1676)

Further reading

[edit]- Karagöz, Erkan (2021). İdil-Ural (Tatar ve Başkurt) sihirli masalları üzerine karşılaştırmalı motif çalışması: Aktarma – motif tespiti (motif - İndex of Folk-Literature'a göre) – motif dizini (in Turkish). Vol. 1. Ankara: Atatürk Kültür Merkezi Başkanlığı. pp. 143-586 (Tatar tales). ISBN 978-975-17-4742-6.

External links

[edit]- Kropotkin, Peter Alexeivitch (1888). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. XXIII (9th ed.). pp. 70–71.

- Kropotkin, Peter Alexeivitch; Eliot, Charles Norton Edgcumbe (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). pp. 448–449.

- The American Turko-Tatar Association

- Tatar peoples

- Ethnic groups in Azerbaijan

- Ethnic groups in Dagestan

- Ethnic groups in Kazakhstan

- Ethnic groups in Poland

- Ethnic groups in Russia

- Ethnic groups in Turkey

- Ethnic groups in Ukraine

- Ethnic groups in Uzbekistan

- Muslim communities of Russia

- Turkic peoples

- Turkic peoples of Asia

- Tatar diaspora

- Tatar people

![Flag of the Crimean Khanate[78]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/90/Coat_of_arms_of_Crimean_Khanate.svg/204px-Coat_of_arms_of_Crimean_Khanate.svg.png)