East Turkestan

East Turkestan شەرقىي تۈركىستان (Uyghur) | |

|---|---|

Extent of East Turkestan in Central Asia, per the East Turkistan Government in Exile | |

| Largest city | Ürümqi |

| Spoken languages | |

| Ethnic groups |

|

| Formation | |

• State of Yettishar (Kashgaria) | November 12, 1864 |

| November 12, 1933 | |

| November 12, 1944 | |

| September 14, 2004 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 1,828,418 km2 (705,956 sq mi), as claimed by the East Turkistan Government in Exile[2] |

| Population | |

• Estimate | 24,870,000[3]30–40 million (claimed by the East Turkistan Government in Exile and the World Uyghur Congress)[2][4] |

| Time zone | Ürümqi Time (UTC+06:00)[5] |

| Part of a series on |

| Uyghurs |

|---|

|

Uyghurs outside of Xinjiang |

| History of Xinjiang |

|---|

|

East Turkestan or East Turkistan (Uyghur: شەرقىي تۈركىستان, ULY: Sherqiy Türkistan, UKY: Шәрқий Туркистан), also called Uyghuristan (ئۇيغۇرىستان, Уйғуристан), is a loosely-defined geographical region in the northwestern part of the People's Republic of China, on the cross roads of East and Central Asia, which varies in meaning by context and usage.[6] The term was coined in the 19th century by Russian Turkologists, including Nikita Bichurin, who intended the name to replace the common Western term for the region, "Chinese Turkestan", which referred to the Tarim Basin in Southern Xinjiang or Xinjiang as a whole during the Qing dynasty.[7][8] Beginning in the 17th century, Altishahr, which means "Six Cities" in Uyghur, became the Uyghur name for the Tarim Basin. Uyghurs also called the Tarim Basin "Yettishar," which means "Seven Cities," and even "Sekkizshahr", which means "Eight Cities" in Uyghur. Chinese dynasties from the Han dynasty to the Tang dynasty had called an overlapping area the "Western Regions".

Starting in the 20th century, Uyghur separatists and their supporters used East Turkestan as an appellation for the whole of Xinjiang (the Tarim Basin and Dzungaria) or for a future independent state in present-day Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. They reject the name Xinjiang (meaning "New Frontier" in Chinese)[9] because of the Chinese perspective reflected in the name, and prefer East Turkestan to emphasize the connection to other, western Turkic groups.

The First East Turkestan Republic existed from November 12, 1933, to April 16, 1934, and the Second East Turkestan Republic existed between November 12, 1944, and June 27, 1946. East Turkestan is a founding member of the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization (UNPO) formed in 1991, where it was represented initially by the East Turkistan National Congress and later by the World Uyghur Congress post 2004.[10] In September 2004, the East Turkistan Government in Exile was established in Washington, D.C.

Etymology

[edit]The term "East Turkestan" was coined in the 19th century by Russian Turkologists, including Nikita Bichurin, who intended the name to replace the common Western term for the region, "Chinese Turkestan", which referred to the Tarim Basin in southern Xinjiang or sometimes Xinjiang as a whole during the Qing dynasty.[7][8] The term "Uyghuristan" means 'land of Uyghurs'.[11][12] The latter name was given to the region by medieval Muslim geographers.[13]

History

[edit]Pre-20th century

[edit]

In China, the term Western Regions (Chinese: 西域; pinyin: Xīyù; Wade–Giles: Hsi1-yü4; Uyghur: Qurighar, Қуриғар)[14][15] referred to the regions west of the Yumen Pass. During the 2nd century BC, Chinese writers called the city states of the northern and southern rim of the Taklamakan Desert the "Walled city-states of the Western Regions".[16] In 60 BC, the Han dynasty established the Protectorate of the Western Regions "in charge of all the oasis-states of the Tarim Basin" which they ruled in indirectly with small agricultural military colonies.[16] The Protector General was stationed at Wulei (west of Karasahr).[17][18] The city-states were able to conduct their own independent policies with each other. After the Western Han period that ended in 9 AD, China lost its authority over the Western Regions until it was restored in 94 AD and officially lasted until 107 AD.[16] After the crackdown of internal separatist forces, the Eastern Han dynasty set up another protectorate known as the Chief Official of the Western Regions instead.[19] Since the Han, successive Chinese governments had to deal with secessionist movements and local rebellions from different peoples in the region.[20] However, even when Xinjiang was not under Chinese political control, Xinjiang has long had "close contacts with China" that distinguish it from the independent Turkic countries of Central Asia.[21] A Sogdian sale contract of a female slave from the period of the Gaochang kingdom under the rule of Qu clan from 639 CE mentioned the Sogdian word "twrkstn", which may have referred to the lands to the east and north of Syr Darya in the realm of the First Turkic Khaganate.[22]: 14, 15

The Gökturks, known in ancient Chinese with pronunciation as Tutkyud as well as modern Chinese pronunciation as Tujue (Tu-chueh; Chinese: 突厥; pinyin: Tūjué; Wade–Giles: T'u1-chüeh2), united the Turkic peoples and created a large empire, which broke into various Khanates or Khaganates; the Western Turkic Khaganate inherited Xinjiang, but West Tujue became part of China's Tang dynasty until the ninth century. However, the terms for West Tujue and East Tujue do not have any relation with the terms West and East Turkestan.[20] "Turkestan", which means "region of the Turks", was defined by Arab geographers in the ninth and tenth centuries as the areas northeast of the Sir River.[23] For those Arab writers, the Turks were Turkic-speaking nomads and not the sedentary Persian-speaking oasis dwellers.[21] With the various migrations and political upheavals following the collapse of the Gökturk confederation and the Mongol invasions, "Turkestan", according to the official Chinese position, gradually ceased to be a useful geographic descriptor and was not used.[24]

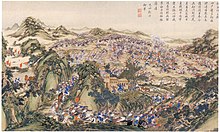

During the sixteenth century, the Chagatai Khanate completed the Islamification and Turkification of western Xinjiang and the surrounding region, known then as Moghulistan, while China's Ming dynasty held the Eastern Areas. After the Fall of the Ming dynasty, a western Mongol group established a polity in "Chinese Tartary", as it was sometimes known, or in eastern Xinjiang, expanding southward into southern Xinjiang.[25] In 1755, the Qing dynasty defeated the Mongol Dzungar Khanate and captured two territories in Xinjiang. The northern territory, where the Dzungars lived, was called Dzungaria, while the southern areas, which the Dzungars controlled and mined, were called Huijiang (Hui-chiang; Chinese: 回疆; pinyin: Huíjiāng; Wade–Giles: Hui2-chiang1; lit. 'Muslim territory') or Altishahr.[21] The term "Xinjiang", which, up until that time, simply meant all territories new to the Qing, gradually shifted in meaning for the Qing court to exclusively mean Dzungaria and Altishahr taken together. In 1764, the Qianlong Emperor made this use of Xinjiang as a proper name official and issued an imperial order defining Xinjiang as a "provincial administrative area". After General Tso (Tso Ts'ung T'ang) suppressed the Dungan revolt in 1882, Xinjiang was officially reorganized into a province and the name Xinjiang was popularized,[23] superseding "Xiyu" in writing.[26]

At the same time as the Chinese consolidation of control in Xinjiang, explorers from the British and Russian Empires explored, mapped, and delineated Central Asia in a competition of colonial expansion. Several influential Russians would propose new terms for the territories, as in 1805 when the Russian explorer Timovski revived the use of "Turkestan" to refer to Middle Asia and "East Turkestan" to refer to the Tarim Basin east of Middle Asia in southern Xinjiang or, in 1829, when the Russian sinologist Nikita Bichurin proposed the use of "East Turkestan" to replace "Chinese Turkestan" for the Chinese territory east of Bukhara.[27] The Russian Empire mused expansion into Xinjiang,[28] which it informally called "Little Bukhara". Between 1851 and 1881, Russia occupied the Ili valley in Xinjiang and continued to negotiate with the Qing for trading and settlement rights for Russians.[29] Regardless of the new Russian appellations, the original inhabitants of Central Asia generally continued not to use the word "Turkestan" to refer to their own territories.[30]

After a spate of annexations in Middle Asia, Russia consolidated its holdings west of the Pamir Mountains as the Turkestan Governorate or "Russian Turkestan" in 1867.[31] It is at this time that Western writers began to divide Turkestan into a Russian and a Chinese part.[24] Although foreigners acknowledged that Xinjiang was a Chinese polity, and that there were Chinese names for the region, some travelers preferred to use "names that emphasized Turkic, Islamic, or Central Asian, i.e., non-Chinese characteristics".[25] For contemporary British travelers and English-language material, there was no consensus on a designation for Xinjiang, with "Chinese Turkestan", "East Turkestan", "Chinese Central Asia", "Serindia",[32] and "Sinkiang" being used interchangeably to describe the region of Xinjiang.[27] Until the 20th century, locals used the names of cities or oases in their "territorial self-perception", which expanded or contracted as needed, such as Kashgaria out of Kashgar to refer to southwestern Xinjiang. Altishahr, or "six cities", collectively referred to six vaguely defined cities south of the Tian Shan.[25]

Early 20th century

[edit]

In 1912, the Xinhai Revolution overthrew the Qing dynasty and created a Republic of China. As Yuan Dahua, the last Qing governor, fled from Xinjiang, one of his subordinates, Yang Zengxin (楊增新), took control of the province and acceded in name to the Republic of China in March of the same year. In 1921, the Soviet Union officially defined the Uyghurs as the sedentary Turkic peoples from Chinese Turkestan as part of their nation building policy in Central Asia.[27] Multiple insurgencies arose against Yang's successor Jin Shuren (金树仁) in the early 1930s throughout Xinjiang, usually led by Hui people.[33] "East Turkestan" became a rallying cry for people who spoke Turki and believed in Islam to rebel against Chinese authorities.[24]

In the Kashgar region on November 12, 1933, Uyghur separatists declared the short-lived[34] and self-proclaimed East Turkestan Republic (ETR), using the term "East Turkestan" to emphasize the state's break from China and new anti-China orientation.[30] Influenced by pan-Islamism and pan-Turkism, these separatists established a constitution which mandated Sharia law in the short-lived Islamic republic.[35]

The First ETR gave political meaning to the erstwhile geographical term of East Turkestan.[21] It was not recognized by any country, however.[35] Chinese warlord Sheng Shicai (盛世才) quickly defeated the ETR and ruled Xinjiang for the decade after 1934 with close support from the Soviet Union.[36]

Eventually, the Soviet Union exploited the change in power from Sheng to Kuomintang officials to create the puppet Second East Turkestan Republic (1944–1946) in present-day Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture to exploit its minerals, later justifying it as a national liberation movement against the "reactionary" Kuomintang regime.[27] Amid the anti-Han programs and policies[36] and exclusion of "pagans",[24] or non-Muslims, from the separatist government, Kuomintang leaders based in Dihua (Ürümqi) appealed to the long Chinese history in the region to justify its sovereignty over Xinjiang. In response, Soviet historians produced revisionist histories to help the ETR justify its own claims to sovereignty, with statements such as that the Uyghurs were the "most ancient Turkic people" that had contributed to world civilization.[27] In June 1946, the Soviet Union withdrew its support for the ETR.[35]

Traditionally, scholars had thought of Xinjiang as a "cultural backwater" compared to the other Central Asian states during the Islamic Golden Age.[25] Local British and US consuls, also intrigued by the separatist government, published their own histories of the region. The Soviet Uyghur histories produced during its support of the ETR remain the basis of Uyghur nationalist publications today.[27]

Late 20th century

[edit]

At the end of the Chinese Civil War in 1949, with Xinjiang divided between Kuomintang forces and ETR secessionists, the Communist leadership persuaded both governments to surrender and accept the succession of the People's Republic of China government[36] and negotiated the establishment of Communist provincial governments in Yining (Ghulja) and Dihua.[37] On October 1, 1955, Chinese Communist Party Chairman Mao Zedong designated Xinjiang a "Uyghur Autonomous Region",[26] creating a regionwide Uyghur identity which overtook Uyghurs' traditionally local and oasis-based identities.[38] Although the Soviet Union initially suppressed the publications of its past Uyghur studies programs, after the Sino-Soviet split in the 1960s, it revived its Uyghur studies program as part of an "ideological war" against China.[27][39] The term "East Turkestan" was popularized in academic works,[20] but inconsistently: at times, the term East Turkestan only referred to as the area in Xinjiang south of the Tian Shan mountains, corresponding to the Tarim Basin;[20] the areas north of the Tian Shan mountains were called Dzungaria or Zungaria.[23][40][41] Tursun Rakhimov, a Uyghur historian for the Communist Party of the Soviet Union during the Sino-Soviet split,[42] argued in his 1981 book "Fate of the Non-Han Peoples of the PRC" that "both" East Turkestan and Dzungaria were conquered by China and "renamed" Xinjiang. Occasionally, he used East Turkestan and Xinjiang interchangeably.[27] Concurrently, during the Cultural Revolution and the Revolution's campaigns against "local nationalism", the government had come to associate the term East Turkestan with Uyghur separatism and "foreign hostile forces" and forbade its usage.[23] Uyghur nationalist historian Turghun Almas and his book Uyghurlar (The Uyghurs) and Uyghur nationalist accounts of history were galvanized by Soviet stances on history, "firmly grounded" in Soviet Turcological works, and both heavily influenced and partially created by Soviet historians and Soviet works on Turkic peoples.[43] Soviet historiography spawned the rendering of Uyghur history found in Uyghurlar.[44] Almas claimed that Central Asia was "the motherland of the Uyghurs" and also the "ancient golden cradle of world culture".[45] The global trends set by the Dissolution of the Soviet Union in the 1990s and the rise of global Islamism[26] and pan-Turkism[46][47] revived separatist sentiments in Xinjiang and led to a wave of political violence that killed 162 people between 1990 and 2001.[20]

21st century

[edit]In 2001, the government of China lifted its ban on state media's using the terms "Uyghurstan"[26] or "East Turkestan",[48] as part of a general opening up after the September 11 attacks to the world about political violence in Xinjiang and a plea for international help to suppress East Turkestan terrorists.[49][20] In 2004, the East Turkistan Government in Exile was established in Washington, D.C. under the leadership of Anwar Yusuf Turani to strive for East Turkistan's independence.[50] To justify the PRC's claim to East Turkestan, a white paper was published in 2019 which made a statement that 'East Turkestan' never existed and it was only called 'Xinjiang' and been part of China since early history.[51] East Turkestan was historically not treated as an inseparable part of China, but rather colonized by Han Chinese who had little in common with the Uyghur population.[51]

On February 28, 2017, it was announced by the Qira County government in Hotan Prefecture that those who reported others for stitching the 'star and crescent moon' insignia on their clothing or personal items or having the words 'East Turkestan' on their mobile phone case, purse, or other jewelry, would be eligible for cash payments.[52]

Current status

[edit]As the history of Xinjiang in particular is contested between the government of China and Uyghur separatists, the official and common name of Xinjiang (with its Uyghur loanword counterpart, Shinjang) is rejected by those seeking independence.[26] "East Turkestan", a term of Russian origin, asserts a continuity with a "West Turkestan" or the now-independent states of Soviet Central Asia.[27] Not all of those states accept the designation of "Turkestan", however. For instance, Tajikistan's Persian-speaking population feels more closely aligned with Iran and Afghanistan.[53] For separatists,[54][55] East Turkestan is coterminous with Xinjiang or the independent state that they would like to lead in Xinjiang.[56] Proponents of the term "East Turkestan" argue that the name Xinjiang is arrogant, because if the individual Chinese characters are to be taken literally and not as a proper name, then Xinjiang means "New Territory".[23] Some Chinese scholars have advocated a name change for the region or a reversion to the older term Xiyu ("Western Regions"), arguing that "Xinjiang" might mislead people into thinking that Xinjiang is "new" to China. Other scholars defend the name, noting that Xinjiang was new to the late Qing dynasty, which gave Xinjiang its current name.[23]

In modern separatist usage,[26] "Uyghuristan", which means "land of the Uyghurs", is a synonym for Xinjiang or a potential state in Xinjiang,[49] like "East Turkestan".[57][39] There is no consensus among separatists about whether to use "East Turkestan" or "Uyghurstan".[25] "East Turkestan" has the advantage of also being the name of two historic political entities in the region, while Uyghurstan appeals to modern ideas of ethnic self-determination. East Turkistan was also used in the context of Yaqub Beg's Kashgaria in the mid-1800s. Uyghurstan is also a difference in emphasis in that it excludes more peoples in Xinjiang than just the Han,[58] but the "East Turkestan" movement[34] is still a Uyghur phenomenon. Kazakhs and Hui Muslims are largely alienated from the movement,[49] as are Uyghurs who live closer to the eastern provinces of China. Separatist sentiment is strongest among the Uyghur diaspora,[26] who practice what has been called "cyber-separatism", encouraging the use of "East Turkestan" on their websites and literature.[59] Historically, "Uyghurstan" referred to the northeastern oasis region of "Kumul-Turfan".[60] "Chinese Turkestan", while synonymous with East Turkestan in historical terms,[40] is not used today, rejected by Uyghur separatists for the "Chinese" part of the name and by China for the "Turkestan" part.[21] In China, the terms "East Turkestan", "Uyghurstan",[58] and even "Turkestan" alone connote old Western imperialism and the past East Turkestan republics and modern militant groups, such as the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM). The government of China conflates the violence of differing separatist groups, such as the ETIM and the East Turkestan Liberation Organization, as coming simply from "East Turkestan forces".[21] Chinese diplomatic missions have objected to foreigners' use of "East Turkestan". They argue that the term is political and no longer geographical or historical and that its use represents "a provocation" to the sovereignty of China.[23] The historical definitions for "East Turkestan" are multifarious and ambiguous, reflecting that, outside of Chinese administration,[25] the area now called "Xinjiang" was not geographically or demographically a single region.[26]

The territorial definition, as claimed by the East Turkistan Government in Exile[2] and International Support for Uyghurs,[61] includes the bulk of Xinjiang (excluding the disputed territory of Aksai Chin), as well as parts of western Gansu (including Subei Mongol Autonomous County, Aksay Kazakh Autonomous County, Dunhuang city, and Guazhou County) and Qinghai (Lenghu and Mangnai). The World Uyghur Congress considers East Turkestan to be the area of Xinjiang along with territory claimed to be annexed by a "neighboring Chinese province" in 1949.[62]

See also

[edit]- Afghan Turkestan

- Chinese Turkestan

- East Turkistan Government in Exile

- History of the Uyghur people

- Xinjiang internment camps

- Pan-Islamism and Pan-Turkism

- Turkic migration

- Qurtulush Yolida

References

[edit]- ^ "VI. Progress in Education, Science and Technology, Culture and Health Work". History and Development of Xinjiang. State Council of the People's Republic of China. May 26, 2003. Archived from the original on January 29, 2011. Retrieved December 31, 2010.

- ^ a b c "East Turkistan at a Glance". East Turkistan Government in Exile. March 4, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2023.

- ^ "National Data". Archived from the original on April 15, 2020. Retrieved April 10, 2020.

- ^ "East Turkistan". World Uyghur Congress. September 29, 2016. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- ^ Kelter, Frederik (August 9, 2023). "Conflict over clocks: China among countries where time is political". Al Jazeera. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

Xinjiang's provincial capital, Urumqi, is geographically two hours behind Beijing ...

- ^ https://books.google.com/books?id=8FVsWq31MtMC&printsec=frontcover&dq=east+turkestan+crossroads+of+east+and+central+asia&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&source=gb_mobile_search&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiuu_2SvaqKAxVyL0QIHRUDPXwQ6AF6BAgGEAM

- ^ a b Kamalov, Ablet (2021). "Uyghur Historiography". In Ludden, David (ed.). Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.637. ISBN 978-0-19-027772-7.

The split of Central Asia into Russian and Chinese domains did not terminate the intensive interactions between the peoples of the areas, which since the 19th century have been known as "Russian" (West) and "Chinese" (East) Turkestan (Greater Turkistan also included parts of other countries, such as Afghanistan).

- ^ a b Kamalov, Ablet (2007). "The Uyghurs as a Part of Central Asian Commonality: Soviet Historiography on the Uyghurs". In Beller-Hann, Ildiko; Cesàro, M. Cristina; Finley, Joanne Smith (eds.). Situating the Uyghurs Between China and Central Asia. Routledge. p. 34. ISBN 9781315243054.

It was Russian scholarship, for instance, that introduced for the first time the terms 'West Turkestan' and 'East Turkestan'. In 1829, the Russian sinologist N. Bichurin stated: 'it would be better here to call Bukhara's Turkestan the Western one, and Chinese Turkestan the Eastern [...]'

- ^ "Introduction". The Lost Frontier Treaty Maps that Changed Qing's Northwestern Boundaries. Archived from the original on January 29, 2020. Retrieved January 29, 2020.

The Qianlong emperor (1736–1796) named the region Xinjiang, for New Territory.

- ^ "UNPO: East Turkestan". Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization. December 16, 2015. Archived from the original on September 7, 2019. Retrieved April 24, 2019.

- ^ "6. From Party to Nation". Uyghur Nation. Harvard University Press. 2016. pp. 173–203. doi:10.4159/9780674970441-009. ISBN 9780674970441.

- ^ Gladney, Dru C. (2000). "New Perspectives on the 'New Region' of China: Reconsidering Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region". Inner Asia. 2 (2): 119–120. doi:10.1163/146481700793647841.

- ^ Brophy, David (2018). "The Uyghurs: Making a Nation". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.318. ISBN 978-0-19-027772-7.

- ^ Tikhvinskiĭ, Sergeĭ Leonidovich and Leonard Sergeevich Perelomov (1981). China and her neighbours, from ancient times to the Middle Ages: a collection of essays. Progress Publishers. p. 124.

- ^ Han, Enze (August 31, 2010). External Kin, Ethnic Identity and the Politics of Ethnic Mobilization in the People's Republic of China (Doctor of Philosophy). The Faculty of Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University. pp. 113–114.

- ^ a b c Bregel 2003, p. 10.

- ^ Hulsewâe, A.F.P.; Idema, W.L.; Zèurcher, E. (1990). Thought and Law in Qin and Han China: Studies Dedicated to Anthony Hulsewâe on the Occasion of His Eightieth Birthday. Vol. 24. E.J. Brill. p. 176. ISBN 978-90-04-09269-3.

- ^ Liu, J.; Chen, M.; Wang, M. (2022). The General Theory of Dunhuang Studies. Springer Nature Singapore. p. 14. ISBN 978-981-16-9073-0.

- ^ Ge, Jianxiong (2018). China's Belt and Road Initiatives - Economic Geography Reformation. Springer Nature Singapore. p. 6.

- ^ a b c d e f Rumer, Eugene B.; Trenin, Dmitrii; Huasheng Zhao (2007). Central Asia: Views from Washington, Moscow, and Beijing. M. E. Sharpe. pp. 141–143.

- ^ a b c d e f Millward, James A. (2007). Eurasian Crossroads:A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press. pp. ix–x, 95.

- ^ 豊, 吉田; 孝夫, 森安; 新疆ウィグル自治区博物館 (1988). 麹氏高昌国時代ソグド文女奴隷売買文書. 神戸市外国語大学外国学研究 神戸市外国語大学外国学研究: 1–50.

- ^ a b c d e f g Rahman, Anwar (2005). Sinicization Beyond the Great Wall: China's Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region. Troubador Publishing Ltd. pp. 20–26.

- ^ a b c d "Origin of the "East Turkistan" Issue". State Council of the People's Republic of China. May 1, 2003. Archived from the original on March 8, 2019. Retrieved February 5, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f Bellér-Hann, Ildikó (2008). "Place and People". Community Matters in Xinjiang, 1880–1949: Towards a Historical Anthropology of the Uyghur. Brill. pp. 35–38, 44–45.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Starr, S. Frederick (2004). Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 6–7, 11, 14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Bellér-Hann, Ildikó (2007). Situating the Uyghurs between China and Central Asia. Ashgate Publishing. pp. 4–5, 32–40.

- ^ Tayler, Jeffrey (2008). Murderers in Mausoleums: Riding the Back Roads of Empire Between Moscow and Beijing. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 244.

Russia, whether or not it had designs on India, was expanding throughout Central Asia and saw no reason that Xinjiang should not belong to the tsar as did other Central Asian lands to the west.

- ^ Rahul, Ram (1997). Central Asia: An Outline History. Concept Publishing Company. p. 88.

- ^ a b Central Asian Review. 13 (1). London: University of Virginia: 5. 1965.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: untitled periodical (link) - ^ Bregel, Yuri (1996). Notes on the Study of Central Asia. Research Institute for Inner Asian Studies.

Strictly speaking, 'Russian Turkestan' as a political term was limited only to the territory of the governorate-general of Turkestan and did not include... the khanates of Bukhara and Khiva

- ^ Meyer, Karl Ernest; Brysac, Shareen Blair (2006). Tournament of Shadows: The Great Game and the Race for Empire in Central Asia. Basic Books. p. 347.

Stein repeatedly crossed 18,000-foot passes, settling down to work in the deserts of Chinese Turkestan. It took 182 packing cases to hold the finds of his third expedition (1913–16) to the region he preferred calling Serindia, from the Greek word for China, Seres, meaning silkworm.

- ^ "Sinkiang: Land at the Back of Nowhere". LIFE. Vol. 15, no. 24. December 1943. pp. 95–103.

The Chinese rule Sinkiang. Every now and then (1970, 1932) they have to contend with a rebellion of the Moslem masses, usually led by Chinese-speaking Moslems.

- ^ a b Pan, Guang (2006). "East Turkestan Terrorism and the Terrorist Arc: China's Post-9/11 Anti-Terror Strategy" (PDF). China and Eurasia Forum Quarterly. 4 (2). Central Asia-Caucasus Institute and Silk Road Studies Program: 19–24. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 6, 2011.

- ^ a b c Zhao, Huasheng (2016). "Central Asia in Chinese Strategic Thinking". The new great game : China and South and Central Asia in the era of reform. Thomas Fingar. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-8047-9764-1. OCLC 939553543.

- ^ a b c Dillon, Michael (2004). Xinjiang: China's Muslim Far Northwest. Psychology Press. pp. 32–35.

- ^ H.A.R. Gibb (1954). "Kuldja". The Encyclopaedia of Islam (new ed.). Brill. p. 364.

- ^ Laçiner, Sedat; Özcan, Mehmet; Bal, İhsan (2001). USAK Yearbook of International Politics and Law. Vol. 3. p. 408.

- ^ a b Shulsky, Abram N. (2000). Deterrence Theory and Chinese Behavior. RAND Corporation. p. 13.

- ^ a b Herbertson, Fanny Dorothea (1903). Asia. Adam & Charles Black. p. xxxv.

Sin-tsiang is made up of the Tarim basin or Chinese (Eastern) Turkestan and Zungaria. The former is a desert with marginal oases where rivers descend from the mountains. The chief centres are Yarkand and Kashgar. Zungaria is a relatively low and fertile steppe land, leading from the low-lands of Southern Siberia to the Mongolian plateau.

- ^ Hughes, William (1892). A Class-Book of Modern Geography. G. Philip & son. p. 238.

Zungaria includes the wild and desolate region between the Thian-Shan and the Altai Mountains, and is bounded by Eastern Turkestan on the south, and by Russian Central Asia on the west.

- ^ Canadian Slavonic Papers. 17. Canadian Association of Slavists: 352. 1975.

[Tursun Rakhimov] is not only the author and editor of a number of Uighur linguistic studies, but also an expert on articles about the persecution of the national minorities in the PRC. One may say that this 'personal union' of the Uighur scholar and the Soviet propagandist once more illustrates the intense interdependence of the status of the Soviet Uighurs and their role in Soviet Policy.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: untitled periodical (link) - ^ Bellér-Hann 2007 Archived August 22, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, p. 42.

- ^ Bellér-Hann 2007 Archived August 22, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, p. 33.

- ^ Bellér-Hann 2007 Archived August 22, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, p. 4.

- ^ Covarrubias, Jack; Lansford, Tom (2007). Strategic Interests in the Middle East: Opposition and Support for US Foreign Policy. Ashgate Publishing. p. 91.

- ^ Roy, Olivier (2005). Turkey Today: A European Country?. Anthem Press. p. 20.

- ^ Gladney, Dru (July 20, 2002). "Ethnic Conflict Prevention in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region: New Models for China's New Region" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved February 5, 2011.

- ^ a b c Van Wie Davis, Elizabeth (January 2008). "Uyghur Muslim Ethnic Separatism in Xinjiang, China". Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies. Archived from the original on October 11, 2017. Retrieved February 6, 2011.

The desired outcome by groups that use violence is, broadly speaking, a separate Uyghur state, called either Uyghuristan or Eastern Turkistan, which lays claim to a large part of China.... The largest [Muslim] group, the Hui who have blended fairly well into Chinese society, regard some Uyghurs as unpatriotic separatists who give other Chinese Muslims a bad name.... China's official statement on "East Turkestan terrorists" published in January 2002 listed several groups allegedly responsible for violence

- ^ "Voice of America Report on Chinese Opposition of ETGIE". Voice of America News. September 14, 2004.

- ^ a b Rukiye Turdush, Uyhgur Research Institute (August 8, 2019). "Genocide as Nation Building: China's Historically Evolving Policy in East Turkistan". The Journal of Political Risk. Archived from the original on December 20, 2021. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ^ Joshua Lipes; Jilil Kashgary (April 4, 2017). "Xinjiang Police Search Uyghur Homes For 'Illegal Items'". Radio Free Asia. Translated by Mamatjan Juma. Archived from the original on December 16, 2019. Retrieved December 16, 2019.

A second announcement, issued February 28 by the Chira (Cele) county government, said those who report individuals for having "stitched the 'star and crescent moon' insignia on their clothing or personal items" or the words "East Turkestan"—referring to the name of a short-lived Uyghur republic—on their mobile phone case, purse or other jewelry, were also eligible for cash payments.

- ^ Humphrey, Caroline; Sneath, David (1999). The End of Nomadism? Society, State, and the Environment in Inner Asia. Duke University Press. pp. v–vi.

- ^ Sheridan, Michael (July 27, 2008). "Islamist bombers target Olympics". The Sunday Times. London. Retrieved February 5, 2011.

The group may be allied with the East Turkestan Islamic Movement – designated a terrorist organisation by the US, China and several other countries – which seeks independence for the Muslim Uighur people of China's far west province of Xinjiang, which Uighur separatists call East Turkestan.

[dead link] - ^ Chung, Chien-peng (July–August 2002). "China's "War on Terror": September 11 and Uighur Separatism". Foreign Affairs. 81 (4): 8–12. doi:10.2307/20033235. JSTOR 20033235. Archived from the original on December 11, 2014. Retrieved February 6, 2011.

Beijing now labels as terrorists those who are fighting for an independent state in the northwestern province of Xinjiang, which the separatists call "Eastern Turkestan."

- ^ Wong, Edward (July 9, 2010). "Chinese Separatists Tied to Norway Bomb Plot". The New York Times. Beijing. Archived from the original on August 27, 2011. Retrieved February 5, 2011.

Many Uighurs call Xinjiang their homeland, and some want an independent state there called East Turkestan.

- ^ Bovingdon, Gardner (2005). Autonomy in Xinjiang: Han nationalist imperatives and Uyghur discontent (PDF). Political Studies 15. Washington: East-West Center. p. 17. ISBN 1-932728-20-1. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 12, 2018. Retrieved February 6, 2011.

- ^ a b Priniotakis, Manolis (October 26, 2001). "China's Secret Separatists: Uyghuristan's Ever-Lengthening Path to Independence". The American Prospect. Archived from the original on October 11, 2017. Retrieved February 5, 2011.

- ^ Moneyhon, Matthew D. (October 2003). "Taming China's 'Wild West': Ethnic Conflict in Xinjiang" (PDF). Peace, Conflict, and Development (5): 9, 17. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 3, 2011. Retrieved February 6, 2011.

- ^ Gladney, Dru C (1990). "The Ethnogenesis of the Uighur". Central Asian Survey. 9 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1080/02634939008400687.

- ^ "East Turkistan". International Support For Uyghurs. Retrieved October 20, 2023.

- ^ "East Turkistan". World Uyghur Congress. September 29, 2016. Retrieved October 20, 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Bregel, Yuri (2003), An Historical Atlas of Central Asia, Brill

- East Turkistan to the Twelfth Century (by William Samolin, 1964)