Ranjit Singh

| Ranjit Singh | |

|---|---|

| Maharaja of Punjab Maharaja of Lahore Sher-e-Punjab (Lion of Punjab) Sher-e-Hind (Lion of India) Sarkar-i-Wallah (Head of Government)[1] Sarkar Khalsaji (Respected Head of the Khalsa) Lord of Five Rivers Singh Sahib[2] | |

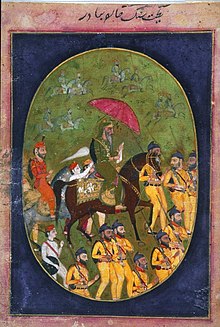

Company School portrait painting of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, Lucknow, Awadh, ca.1810–20 | |

| Maharaja of the Sikh Empire | |

| Reign | 12 April 1801 – 27 June 1839 |

| Investiture | 12 April 1801 at Lahore Fort |

| Successor | Kharak Singh |

| Chief of Sukerchakia Misl | |

| Reign | 15 April 1792 – 11 April 1801 |

| Predecessor | Maha Singh |

| Born | Buddh Singh 13 November 1780[3] Gujranwala, Sukerchakia Misl, Sikh Confederacy (present-day Punjab, Pakistan) |

| Died | 27 June 1839 (aged 58) Lahore, Sikh Empire (present-day Punjab, Pakistan) |

| Burial | Cremated remains stored in the Samadhi of Ranjit Singh, Lahore |

| Spouse | Mehtab Kaur Datar Kaur Jind Kaur See list for others |

| Issue among others... | Kharak Singh Sher Singh Duleep Singh |

| House | Sukerchakia |

| Father | Maha Singh |

| Mother | Raj Kaur |

| Religion | Sikhism |

| Signature (handprint) |  |

Ranjit Singh (13 November 1780 – 27 June 1839) was the founder and first maharaja of the Sikh Empire, ruling from 1801 until his death in 1839. He ruled the northwest Indian subcontinent in the early half of the 19th century. He survived smallpox in infancy but lost sight in his left eye. He fought his first battle alongside his father at age 10.

After his father died around Ranjit's early teenage years, Ranjit subsequently fought several wars to expel the Afghans throughout his teenage years. At the age of 21, he was proclaimed the "Maharaja of Punjab".[4][5] His empire grew in the Punjab region under his leadership through 1839.[6][7]

Before his rise, the Punjab region had numerous warring misls (confederacies), twelve of which were under Sikh rulers and one Muslim.[5] Ranjit Singh successfully absorbed and united the Sikh misls and took over other local kingdoms to create the Sikh Empire.[8] He repeatedly defeated invasions by outside armies, particularly those arriving from Afghanistan, and established friendly relations with the British.[9]

Ranjit Singh's reign introduced reforms, modernisation, investment in infrastructure and general prosperity.[10][11] His Khalsa army and government included Sikhs, Hindus, Muslims and Europeans.[12] His legacy includes a period of Sikh cultural and artistic renaissance, including the rebuilding of the Harmandir Sahib in Amritsar as well as other major gurdwaras, including Takht Sri Patna Sahib, Bihar and Hazur Sahib Nanded, Maharashtra under his sponsorship.[13][14] Ranjit Singh was succeeded by his son Kharak Singh. Ranjit Singh also founded the Order of the Propitious Star of Punjab in 1837. Singh is known by several titles such as Sher-e-Punjab ("Lion of Punjab") and Sarkar-e Wallah (Head of Government).

Early years

Ranjit Singh was born in a Sandhawalia Jat Sikh family on 13 November 1780 to Maha Singh and Raj Kaur in Gujranwala, Punjab region (present-day Punjab, Pakistan). His mother Raj Kaur was the daughter of Sidhu Jat Sikh ruler Raja Gajpat Singh of Jind.[15][16][note 1] Upon his birth, he was named Buddh Singh after his ancestor who was first in line to take Amrit Sanchaar. The child's name was changed to Ranjit (literally, "victor in battle") Singh ("lion") by his father to commemorate his army's victory over the Chattha chieftain Pir Muhammad.[4][19]

Ranjit Singh contracted smallpox as an infant, which resulted in the loss of sight in his left eye and a pockmarked face.[4] He was short in stature, never schooled, and did not learn to read or write anything beyond the Gurmukhi alphabet.[20] However, he was trained at home in horse riding, musketry and other martial arts.[4]

At age 12, his father died.[21] He then inherited his father's Sukerchakia Misl estates and was raised by his mother Raj Kaur, who, along with Lakhpat Rai, also managed the estates.[4] The first attempt on his life was made when he was 13, by Hashmat Khan, but Ranjit Singh prevailed and killed the assailant instead.[22] At age 18, his mother died and Lakhpat Rai was assassinated, and thereon he was helped by his mother-in-law from his first marriage.[23]

Personal life

Wives

In 1789, Ranjit Singh married his first wife Mehtab Kaur,[24] the muklawa happened in 1796.[21] She was the only daughter of Gurbaksh Singh Kanhaiya and his wife Sada Kaur. She was the granddaughter of Jai Singh Kanhaiya, the founder of the Kanhaiya Misl.[4] This marriage was pre-arranged in an attempt to reconcile warring Sikh misls, Mehtab Kaur was betrothed to Ranjit Singh in 1786. The marriage, however, failed, with Mehtab Kaur never forgiving the fact that her father had been killed in battle with Ranjit Singh's father, and she mainly resided with her mother after marriage. The separation became complete when Ranjit Singh married Datar Kaur of the Nakai Misl in 1797 and she turned into Ranjit's most beloved wife.[25] Mehtab Kaur had three sons, Ishar Singh who was born in 1804 and died in infancy. In 1807 she had Sher Singh and Tara Singh. According to historian Jean-Marie Lafont, she was the only one to bear the title of Maharani. She died in 1813, after suffering from failing health.[26]

His second marriage was to, Datar Kaur (Born Raj Kaur) the youngest child and only daughter of Ran Singh Nakai, the third ruler of the Nakai Misl and his wife Karman Kaur. They were betrothed in childhood by Datar Kaur's eldest brother, Sardar Bhagwan Singh, who briefly became the chief of the Nakai Misl, and Ranjit Singh's father Maha Singh. They were married in 1797;[27] this marriage was a happy one and Ranjit Singh always treated Raj Kaur with love and respect.[28] Since Raj Kaur was also the name of Ranjit Singh's mother, his wife was renamed Datar Kaur. In 1801, she gave birth to their son and heir apparent, Kharak Singh.[23] Datar Kaur bore Ranjit Singh two other sons, Rattan Singh and Fateh Singh.[29][30][31] Like his first marriage, the second marriage also brought him a strategic military alliance.[23] Along with wisdom and all the chaste virtues of a noblewoman, Datar Kaur was exceptionally intelligent and assisted Ranjit Singh in affairs of the State.[32] During the expedition to Multan in 1818, she was given command alongside her son, Kharak Singh.[33][34][35] Throughout his life she remained Ranjit Singh's favorite[36] and for no other did he have greater respect for than Datar Kaur, who he affectionately called Mai Nakain.[37][38][39]

Even though she was his second wife she became his principal wife and chief consort.[40][41] During a hunting trip with Ranjit Singh, she fell ill and died on 20 June 1838.[42][43]

Ratan Kaur and Daya Kaur were wives of Sahib Singh Bhangi of Gujrat (a misl north of Lahore, not to be confused with the state of Gujarat).[44] After Sahib Singh's death, Ranjit Singh took them under his protection in 1811 by marrying them via the rite of chādar andāzī, in which a cloth sheet was unfurled over each of their heads. The same with Roop Kaur, Gulab Kaur, Saman Kaur, and Lakshmi Kaur who looked after Duleep Singh when his mother Jind Kaur was exiled. Ratan Kaur had a son Multana Singh in 1819, and Daya Kaur had two sons Kashmira Singh and Pashaura Singh in 1821.[45][46]

Jind Kaur, the final spouse of Ranjit Singh. Her father, Manna Singh Aulakh, extolled her virtues to Ranjit Singh, who was concerned about the frail health of his only heir Kharak Singh. The Maharaja married her in 1835 by 'sending his arrow and sword to her village'. On 6 September 1838 she gave birth to Duleep Singh, who became the last Maharaja of the Sikh Empire.[47]

His other wives included, Mehtab Devi of Kangara also called Guddan or Katochan and Raj Banso, daughters of Raja Sansar Chand of Kangra.

He was also married to Rani Har Devi of Atalgarh, Rani Aso Sircar and Rani Jag Deo According to the diaries, that Duleep Singh kept towards the end of his life, these women presented the Maharaja with four daughters. Dr. Priya Atwal notes that the daughters could be adopted.[24] Ranjit Singh was also married to Jind Bani or Jind Kulan, daughter of Muhammad Pathan from Mankera and Gul Bano, daughter of Malik Akhtar from Amritsar.

Ranjit Singh married many times, in various ceremonies, and had twenty wives.[48][49] Sir Lepel Griffin, however, provides a list of just sixteen wives and their pension list. Most of his marriages were performed through chādar andāz.[50] Some scholars note that the information on Ranjit Singh's marriages is unclear, and there is evidence that he had many concubines. Dr. Priya Atwal presents an official list of Ranjit Singh's thirty wives.[34] The women married through chādar andāzī were noted as concubines and were known as the lesser title of Rani (queen).[35] While Mehtab Kaur and Datar Kaur officially bore the title of Maharani (high queen), Datar Kaur officially became the Maharani after the death of Mehtab Kaur in 1813. Throughout her life was referred to as Sarkar Rani.[51] After her death, the title was held by Ranjit's youngest widow Jind Kaur.[52] According to Khushwant Singh in an 1889 interview with the French journal Le Voltaire, his son Dalip (Duleep) Singh remarked, "I am the son of one of my father's forty-six wives."[26] Dr. Priya Atwal notes that Ranjit Singh and his heirs entered a total of 46 marriages.[53] But Ranjit Singh was known not to be a "rash sensualist" and commanded unusual respect in the eyes of others.[54] Faqir Sayyid Vaḥiduddin states: "If there was one thing in which Ranjit Singh failed to excel or even equal the average monarch of oriental history, it was the size of his harem."[55][54] George Keene noted, "In hundreds and in thousands the orderly crowds stream on. Not a bough is broken off a wayside tree, not a rude remark to a woman".[54]

Issues

Issues of Ranjit Singh

- Kharak Singh (22 February 1801 – 5 November 1840) was the eldest and the favorite of Ranjit Singh from his second wife, Datar Kaur.[56] He succeeded his father as the Maharaja.

- Ishar Singh (1804-1805) son of his first wife, Mehtab Kaur. This prince died in infancy.

- Rattan Singh (1805–1845) was born to Maharani Datar Kaur.[57][58] He was granted the Jagatpur Bajaj estate as his jagir.

- Fateh Singh (1806-1811) was born to Maharani Datar Kaur.[59]

- Sher Singh (4 December 1807 – 15 September 1843) was the elder of the twins of Mehtab Kaur. He briefly became the Maharaja of the Sikh Empire.

- Tara Singh (4 December 1807 – 1859) younger of the twins born of Mehtab Kaur.

- Multana Singh (1819–1846) son of Ratan Kaur.

- Kashmira Singh (1821–1844) son of Daya Kaur.

- Pashaura Singh (1821–1845) younger son of Daya Kaur.

- Duleep Singh (4 September 1838 – 22 October 1893), the last Maharaja of the Sikh Empire. Ranji Singh's youngest son, the only child of Jind Kaur.

According to the pedigree table and Duleep Singh's diaries that he kept towards the end of his life another son Fateh Singh was born to Mai Nakain, who died in infancy.[60] According to Henry Edward only Datar Kaur and Jind Kaur's sons are Ranjit Singh's biological sons.[61][62]

It is said that Ishar Singh was not the biological son of Mehtab Kaur and Ranjit Singh, but only procured by Mehtab Kaur and presented to Ranjit Singh who accepted him as his son.[63] Tara Singh and Sher Singh had similar rumours, it is said that Sher Singh was the son of a chintz weaver, Nahala and Tara Singh was the son of Manki, a servant in the household of Sada Kaur. Henry Edward Fane, the nephew and aide-de-camp to the Commander-in-Chief, India, General Sir Henry Fane, who spent several days in Ranjit Singh's company, reported, "Though reported to be the Maharaja's son, Sher Singh's father has never thoroughly acknowledged him, though his mother always insisted on his being so. A brother of Sher, Tara Singh by the same mother, has been even worse treated than himself, not being permitted to appear at court, and no office given him, either of profit or honour." Five Years in India, Volume 1, Henry Edward Fane, London, 1842[full citation needed][page needed]

Multana Singh, Kashmira Singh and Pashaura Singh were sons of the two widows of Sahib Singh, Daya Kaur and Ratan Kaur, whom Ranjit Singh took under his protection and married. These sons, are said to be, not biologically born to the queens and only procured and later presented to and accepted by Ranjit Singh as his sons.[64]

Punishment by the Akal Takht

In 1802, Ranjit Singh married Moran Sarkar, a Muslim nautch girl. This action, and other non-Sikh activities of the Maharaja, upset orthodox Sikhs, including the Nihangs, whose leader Akali Phula Singh was the Jathedar of the Akal Takht.[65] When Ranjit Singh visited Amritsar, he was called outside the Akal Takht, where he was made to apologise for his mistakes. Akali Phula Singh took Ranjit Singh to a tamarind tree in front of the Akal Takht and prepared to punish him by flogging him.[65] Then Akali Phula Singh asked the nearby Sikh pilgrims whether they approved of Ranjit Singh's apology. The pilgrims responded with Sat Sri Akal and Ranjit Singh was released and forgiven. An alternative holds that Ranjit went to visit Moran on his arrival in Amritsar before paying his respects at Harmandir Sahib Gurdwara, which upset orthodox Sikhs and hence was punished by Akali Phula Singh. Iqbal Qaiser and Manveen Sandhu make alternative accounts of the relationship between Moran and the Maharaja; the former states they never married, while the latter states that they married. Court chronicler, Sohan Lal Suri makes no mention of Moran's marriage to the Maharaja or coins being struck in her name. Bibi Moran spent the rest of life in Pathankot.[66] Duleep Singh makes a list of his father's queens which also does not mention Bibi Moran.

Establishment of the Sikh Empire

circa 1816–29

Historical context

After the death of Aurangzeb in 1707, the Mughal Empire fell apart and declined in its ability to tax or govern most of the Indian subcontinent. In the northwestern region, particularly the Punjab, the creation of the Khalsa community of Sikh warriors by Guru Gobind Singh accelerated the decay and fragmentation of the Mughal power in the region.[67] Raiding Afghans attacked the Indus river valleys but met resistance from both organised armies of the Khalsa Sikhs as well as irregular Khalsa militias based in villages. The Sikhs had appointed own zamindars, replacing the previous Muslim revenue collectors, which provided resources to feed and strengthen the warriors aligned with Sikh interests.[67] Meanwhile, colonial traders and the East India Company had begun operations in India on its eastern and western coasts.[67]

By the second half of the 18th century, the northwestern parts of the Indian subcontinent (now Pakistan and parts of north India) were a collection of fourteen small warring regions.[5] Of the fourteen, twelve were Sikh-controlled misls (confederacies), one named Kasur (near Lahore) was Muslim controlled, and one in the southeast was led by an Englishman named George Thomas.[5] This region constituted the fertile and productive valleys of the five rivers – Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Bias and Sutlej.[44] The Sikh misls were all under the control of the Khalsa fraternity of Sikh warriors, but they were not united and constantly warred with each other over revenue collection, disagreements, and local priorities; however, in the event of external invasion such as from the Muslim armies of Ahmed Shah Abdali from Afghanistan, they would usually unite.[5]

Towards the end of 18th century, the five most powerful misls were those of Sukkarchakkia, Kanhayas, Nakkais, Ahluwalias and Bhangi Sikhs.[5][21] Ranjit Singh belonged to the first, and through marriage had a reliable alliance with Kanhayas and Nakkais.[5] Among the smaller misls, some such as the Phulkias misl had switched loyalties in the late 18th century and supported the Afghan army invasion against their Khalsa brethren.[5] The Kasur region, ruled by Muslims, always supported the Afghan invasion forces and joined them in plundering Sikh misls during the war.[5]

Rise to fame, early conquests

Ranjit Singh's fame grew in 1797, at age 17, when the Afghan Muslim ruler Shah Zaman, of the Ahmad Shah Abdali dynasty, attempted to annex the Panjab region into his control through his general Shahanchi Khan and 12,000 soldiers.[4][5] The battle was fought in the territory that fell in Ranjit Singh's controlled misl, whose regional knowledge and warrior expertise helped resist the invading army. This victory at the Battle of Amritsar (1798) gained him recognition.[4] In 1798, the Afghan ruler sent in another army, which Ranjit Singh did not resist. He let them enter Lahore, then encircled them with his army, blocked off all food and supplies, and burnt all crops and food sources that could have supported the Afghan army. Much of the Afghan army retreated back to Afghanistan.[4]

In 1799, Raja Ranjit Singh's army of 25,000 Khalsa, supported by another 25,000 Khalsa led by his mother-in-law Rani Sada Kaur of Kanhaiya misl, in a joint operation attacked the region controlled by Bhangi Sikhs centered around Lahore. The rulers escaped, marking Lahore as the first major conquest of Ranjit Singh.[5][68] The Sufi Muslim and Hindu population of Lahore welcomed the rule of Ranjit Singh.[4] In 1800, the ruler of the Jammu region ceded control of his region to Ranjit Singh.[69]

In 1801, Ranjit Singh proclaimed himself as the "Maharaja of Punjab", and agreed to a formal investiture ceremony, which was carried out by Baba Sahib Singh Bedi – a descendant of Guru Nanak. On the day of his coronation, prayers were performed across mosques, temples and gurudwaras in his territories for his long life.[70] Ranjit Singh called his rule "Sarkar Khalsa", and his court "Darbar Khalsa". He ordered new coins to be issued in the name of Guru Nanak named the "NanakShahi" ("of the Emperor Nanak").[4][71][72]

Maharaja of Punjab

Ranjit Singh was initially hesitant to assume the title of Maharajah, fearing it might provoke other chiefs to conspire against him. However, he eventually recognized the benefits of formalizing his rule and was proclaimed Maharajah of the Punjab on April 12, 1801. This move was popular among the masses, who had been without a ruler or government for centuries. The coronation ceremony, led by Sahib Singh Bedi, included a royal salute and Ranjit Singh riding an elephant, showering gold and silver coins on his subjects[73]

Ranjit Singh demonstrated his political acumen by balancing his role as Maharajah with his humble beginnings as a peasant leader. He refused to wear royal emblems or sit on a throne, instead opting for simple attire and holding court in a chair or on cushions. He introduced the Nanak Sahi coins, bearing Guru Nanak's image, and established the Sarkar Khalsaji government, emphasizing the people's role in its creation.[74]

As Maharajah, Ranjit Singh claimed sovereignty over all Sikhs and the people of Punjab, demanding tribute from territories that had previously paid revenue to Lahore. He did not recognize any earthly superior, deriving his title from the PanthKhalsaji. This assurance propelled him to conquer and annex neighboring regions. Ranjit Singh implemented various administrative reforms, including repairing city walls and gates, establishing wards under headmen, and reorganizing justice administration. He set up separate courts for Muslims, governed by Shariat Law, and others for those preferring customary law. He also opened dispensaries providing free Greek medicine.[74]

Ranjit Singh maintained the existing agricultural system and land revenue, ensuring revenue collection directly from cultivators. He guaranteed ownership of wells and land to cultivators, with proprietors holding nominal titles. Ranjit Singh promoted interfaith harmony, participating in Hindu and Muslim festivities, such as Dussehra, Divali, Holi, and Basant. He ensured equal rights and duties for Muslims, Hindus, and Sikhs in his Punjabi state.[74]

Conquest of Kasur, Kangra

Ranjit Singh launched a strategic campaign against the Pathans of Kasur and the Rajputs of Kangra, targeting key Afghan collaborators, Nizamuddin Khan and Sansar Chand. This move aimed to consolidate power and unify the Punjab. Fateh Singh Ahluwalia led the charge against Kasur, decisively crushing the Pathan resistance. Nizamuddin Khan was compelled to pay a substantial indemnity and acknowledge Ranjit Singh's sovereignty, marking a significant victory. Meanwhile, Sansar Chand sparked conflict by seizing villages from Sada Kaur's estates. Ranjit Singh responded swiftly, reclaiming the villages and capturing parts of Kangra territory, including the prosperous towns of Nurpur and Naushera. This demonstration of military prowess reinforced Ranjit Singh's authority.

During his return to Lahore, Ranjit Singh formed a pivotal alliance with Fateh Singh Ahluwalia at Taran Taran. They exchanged turbans, becoming "dharam bhai" (brothers in faith), and pledged to share friends and enemies. Ranjit Singh agreed to allocate at least one district to Fateh Singh in every joint conquest, cementing their partnership. Ranjit Singh's policy toward displaced chieftains was remarkably humane. Although their forts and militias were seized, they received jagirs to support their families, and their sons were offered army positions. This approach aimed to unify the Punjab, rather than enrich individuals, as confiscated territories were assigned to loyal subjects who provided troops.

The alliance between Ranjit Singh and Fateh Singh Ahluwalia transformed them into the Punjab's most powerful united force. They continued their conquests, capturing Pindi Bhattian, Pothohar, and Chiniot from Muslim chiefs. However, during their absence, Nizamuddin Khan plundered villages near Lahore, prompting Ranjit Singh to swiftly respond. Ranjit Singh besieged Kasur fort until Nizamuddin surrendered, demonstrating his military prowess. Despite defeating Nizamuddin twice, Ranjit Singh showed remarkable generosity by pardoning him. This benevolence extended to the family of Nawab Muzaffar Khan of Multan.[75]

Multan's complex history and resistance posed significant challenges. Despite this, Ranjit Singh aimed to reintegrate it into the Punjab. His troops defeated Nawab Muzaffar Khan's peasant mob, capturing the city, except for the central fort. Muzaffar Khan ultimately submitted, paying indemnity and agreeing to pay revenues to Lahore instead of Kabul.[76]

Capture of Amritsar

After conquering Multan, Ranjit Singh set his sights on Amritsar, a city that was the commercial heartbeat of the Punjab province. Although not the largest city, Amritsar was a vital trading hub in northern India, attracting caravans from Central Asia that brought exotic goods such as silks, muslins, spices, tea, coffee, hides, matchlocks, and other armaments. The city's narrow, winding streets were lined with business houses that traded in every conceivable commodity, supported by subsidiary trades like gold- and silversmiths that catered to the wealthy merchants[77]

Amritsar held great significance for the Sikhs, and anyone who aspired to lead the Khalsa and become the Maharajah of the Punjab had to claim the city to legitimize their title. However, Amritsar was fragmented, with nearly a dozen families controlling different parts of the city. These families had built fortresses in their localities and employed armed tax collectors who frequently exploited traders and shopkeepers. The leading citizens, weary of this chaotic situation, approached Ranjit Singh, who needed little convincing to take over the city. The only significant opposition came from the widow of the Bhangi Sardar, who had died three years earlier, and her supporters, the Ramgarhias, who occupied the fort of Gobindgarh. Ranjit Singh strategically conquered the city piece by piece, overpowering the Sardars one by one. The Ramgarhias failed to aid the Bhangi widow, leading to her surrender in exchange for a pension for herself and her son. This victory brought Gobindgarh under Ranjit Singh's control, along with five massive cannons, including the legendary Zamzama[78]

Additionally, Ranjit Singh enlisted the services of Phula Singh, a skilled soldier who had helped him capture the city. The Maharajah's triumph was celebrated with a grand welcome in Amritsar, where he rode through the streets on an elephant, showering coins on the crowds. He also bathed in the pool at the Harimandir and pledged to rebuild the temple in marble and cover it with gold leaf[79]

Treaty of Lahore, 1709

Ranjit Singh's decade-long rule over Lahore marked significant progress in securing the Punjab's borders. The northwestern and northeastern frontiers, once vulnerable to Afghan and Rajput-Gurkha invasions, were now stable, as internal conflicts distracted potential aggressors. Meanwhile, the English East India Company's expansion had transformed the Indian landscape, establishing dominance over most regions except Punjab and Sindh.[80]

Ranjit Singh solidified his control north of the Sutlej River, annexing Kasur, collecting tributes from Multan and northwest Punjab's Muslim chiefs, and subjugating the Majha misls ¹. The remaining misls between the Sutlej and Jumna rivers were the last hurdle to unifying the Punjab. Ranjit Singh's sovereignty over the Cis-Sutlej states was a de facto reality, acknowledged by the populace and reluctantly accepted by local chiefs. However, the English posed a significant challenge. Following their victory over the Marathas, they had become the dominant force in India, with the river Jumna marking the western boundary of their possessions, The East India Company's financial recovery and renewed interest in expansionism heightened tensions.[81]

Napoleon Bonaparte's conquests in Europe altered the dynamics. The Treaty of Tilsit between Napoleon and Tsar Alexander raised concerns about a potential Franco-Russian alliance against England. This led the British to reassess their policies and strengthen defenses against a possible invasion through Persia, Afghanistan, and the Punjab.[82]

Lord Minto, the new governor-general, initiated preparations to counter this threat. British troops were deployed to Karnal, and a military post was established to safeguard Delhi ¹. The Cis-Sutlej chiefs, sensing the shifting balance of power, sought English protection, fearing Ranjit Singh's expansion would abolish their autonomy. A wise elder among the chiefs succinctly summarized their concerns: "Both the British and Ranjit Singh threaten our existence, but British protection would be a slow consumption, whereas Ranjit Singh's arrival would be a swift paralysis, destroying us within hours". This poignant warning underscored the precarious position of the Cis-Sutlej chiefs, caught between two expanding empires.[83]

A delegation consisting of prominent leaders, Bhag Singh of Jind, Lal Singh of Kaithal, Bhagwan Singh of Jagadhari, and representatives of Patiala and Nabha, sought an audience with the Resident at Delhi. They presented a comprehensive memorandum emphasizing their expectation of protection from the English against Ranjit Singh, as they now regarded the English as the supreme authority following the decline of the Mughals and Marathas. The Resident forwarded the memorandum to the governor-general without making any commitments.

The Company's policy, "no farther than the Jumna," led the governor-general to decide that the representation should be officially disregarded. Meanwhile, Maharajah Ranjit Singh invited the Malwa chiefs to Amritsar, assuring them that he did not intend to annex their states and offering them equal association with the Durbar. The chiefs agreed to align with their countrymen, acknowledging that they had to establish terms with one of the dominant powers. At this juncture, Metcalfe arrived in Punjab with the objective of securing Ranjit Singh's support against potential French invasion. However, several factors raised doubts about Metcalfe's intentions. France's distant location and lack of evidence regarding an invasion plan contrasted with British efforts to form alliances with Afghanistan and Sindh, traditional adversaries of the Punjabis and Sikhs.[84]

The governor-general's instructions to Metcalfe revealed that the British government did not claim rights over the Sikh chiefs of Malwa. Metcalfe was advised to avoid explicit concurrence with Ranjit Singh's hostile designs and instead aim for a cordial union of interests. Metcalfe met with the Malwa chiefs at Patiala, where Sahib Singh symbolically presented the keys of his citadel, seeking British protection.

As tensions rose, the chiefs began to manipulate the situation, informing Ranjit Singh of British intentions to annex Durbar's territories and telling Metcalfe that the Durbar was preparing to fight the British. The first meeting between Ranjit Singh and Metcalfe took place on September 12, 1808, at Khem Karan. Metcalfe emphasized the need for unity against French invasion, but Ranjit Singh proposed a broader alliance.

Ranjit Singh requested recognition of his sovereignty over Malwa, but Metcalfe declined, citing the one-sided nature of the request. Azizuddin countered that settling a common frontier was a mutual interest. As negotiations stalled, Ranjit Singh marched to Faridkot to quell a rebellion and Metcalfe presented a draft treaty outlining joint action against France, British troop passage, and military depots. In response, the Durbar proposed a counter-treaty emphasizing most favored nation treatment, non-preference to Afghanistan and Multan, recognition of Ranjit Singh's suzerainty, and a perpetual alliance.[85]

Metcalfe forwarded the counterproposals to Governor-General Lord Minto, but little did he know that the British government had already decided to protect the region between the Jumna and Sutlej rivers, undermining Ranjit Singh's authority. Meanwhile, the Maharajah continued his triumphant march through the region, asserting his control over the area. from Faridkot, Ranjit Singh proceeded to Malerkotla, where Metcalfe followed, witnessing the Pathan ruler's submission to the Maharajah. However, Metcalfe had to tactfully ignore the Nawab's plea to intervene on his behalf and reduce the imposed levy.

Ranjit Singh's journey then took him to Ambala and Shahabad, where he received warm welcomes from the people. His receptive audience was a testament to his growing influence in the region. Upon arriving at Patiala, Sahib Singh, still fearful, begged for forgiveness. Ranjit Singh, demonstrating his magnanimity, forgave Sahib Singh, embraced him, and exchanged turbans as a symbol of their renewed alliance. This gesture cemented Ranjit Singh's position as the suzerain of the area, solidifying his control over the land between the Jumna and Sutlej rivers. Unbeknownst to the Maharajah, Governor-General Lord Minto had devised a plan to undermine his authority.

Lord Minto instructed Metcalfe to prolong negotiations until Colonel Ochterlony's forces were prepared to advance. Meanwhile, Ranjit Singh returned to Amritsar, where he received a hero's welcome. The city erupted in joy, with songs, flowers, and illuminations filling the streets and temple for several nights. The monarch and his people reveled in celebration, blissfully unaware of the impending threat.

Metcalfe arrived in Amritsar on December 10, 1808, bearing the governor-general's ultimatum. Despite the gravity of his mission, he enthusiastically joined the Maharajah's nautch parties. However, his true intentions were to stall for time until Ochterlony was in position, British agents had reestablished contact with the Malwa chiefs, and his colleague Elphinstone had completed his mission in Kabul and returned to British territory.

Metcalfe presented an "irrevocable demand" to Maharajah Ranjit Singh, insisting that all territory east of the Sutlej River, conquered since the English mission's arrival, be restored immediately. This ultimatum prompted the Maharajah to halt the celebrations and return to Lahore for emergency consultations with his ministers. Upon his return, Metcalfe revealed that a British force was advancing towards the Sutlej River. The Durbar's counselors were divided, with Mohkam Chand advocating for resistance, believing it more honorable to die fighting than surrender without a struggle. Conversely, Fakir Azizuddin recommended appeasement to avoid hostilities. The Maharajah ultimately accepted Azizuddin's counsel due to the British forces' swift movement.

On January 2, 1809, Ochterlony departed Delhi for Karnal, leading three infantry battalions, a cavalry regiment, and artillery. His objectives were to compel the Durbar to relinquish its recent conquests and secure assistance from the Malwa chiefs. If any chiefs showed sympathy with Ranjit Singh, they were to be warned of the consequences. As Ochterlony marched north, Metcalfe urged his government to prepare for full-scale war against the Durbar. However, Napoleon's attack on Spain altered the situation, rendering French invasion unlikely. Consequently, British policy shifted, and Ochterlony received new instructions on January 30, 1809. The war, if necessary, would be defensive, focusing on preventing Punjabi crossings of the Sutlej River.

Ochterlony continued his advance, receiving a jubilant welcome from Sahib Singh at Patiala. Nabha and Bhag Singh of Jind showed more restraint, having received favors from Ranjit Singh. The Malerkotla Nawab was reinstated in his possessions. On February 9, Ochterlony issued a proclamation reaffirming British friendship with the Maharajah and warning against crossing the Sutlej River. ultimately, the Maharajah swallowed his pride and acknowledged the Sutlej River as the Punjab's eastern boundary. He returned to Amritsar, where the treaty's details were to be discussed, marking a significant turning point in the region's politics.

The tense negotiations between the Durbar and the British had almost reached a boiling point, with a minor skirmish between Phula Singh's nihangs and Metcalfe's Muslim escort threatening to escalate into full-blown conflict. Fortunately, the governor-general intervened just in time, dispatching draft treaties to the Durbar. These treaties proposed perpetual friendship, most-favored-nation treatment, recognition of the Maharajah's sovereignty north of the Sutlej, and permission for Durbar troops to remain south of the river to police their estates. The Durbar troops relinquished occupied territories, and the treaty was formally signed at Amritsar on April 25.

Metcalfe's departure was marked by farewell parties, but underlying tensions persisted. Pro-war factions within the Durbar, led by Mohkam Chand and Akali Phula Singh, advocated tearing up the treaty and fighting. Rumors of a Sikh-Maratha alliance to expel the English spread, prompting the British to deploy troops to Hansi. Maharajah Ranjit Singh remained cautious, refusing to take Maratha promises seriously. "Let the Marathas make the first move, and I will join them," he told his courtiers. As months passed, rumors dissipated, and relations between the Durbar and English normalized.

By June, the governor-general expressed satisfaction with their relations, and Ranjit Singh responded enthusiastically. However, the Treaty of Lahore dealt a significant blow to Punjabi unity, permanently separating Malwa from the rest of the country. Malwai chieftains resumed their infighting, and the British discovered they needed protection against each other. Consequently, on August 22, 1811, the British issued a proclamation authorizing interference when Malwai chiefs took the law into their own hands.

Within two to three years, the British transitioned from protectors to sovereign powers, effectively annexing Malwa and integrating it into British India. The Malwais became spectators to the independent Punjabi state's military achievements. Initially, the treaty secured the Durbar's eastern frontier and guaranteed non-interference in its expansion plans. However, the British later used this treaty to thwart the Durbar's moves against Sindh, the north, and northwest[86]

Millitary Campaigns

Consolidation of the Panjab

Maharajah Ranjit Singh sought to eliminate independent principalities near Lahore, leading him to launch an expedition against Kasur in 1807. Jodh Singh Ramgarhia and Akali Phula Singh, with his fearless Nihangs, played pivotal roles in the campaign. On February 10, 1807, the battle commenced, forcing Afghan forces to retreat into the fort. The Sikhs besieged the fort, engaging in intermittent bombardments and skirmishes for a month. Phula Singh's Nihangs then made a daring breach in the fort wall, prompting Sharf-ud-din and others to flee, while Qutb-ud-din was captured. Kasur's annexation was complete by March 1807.

Ranjit Singh allowed Qutb-ud-din to retain control over the Mamdot territory, approximately 400 square miles on the River Satluj's left bank, in exchange for a nominal tribute and military service with 100 horsemen whenever required. Following the Treaty of Amritsar in 1809, Qutb-ud-din attempted to secure British protection but was rebuffed since Mamdot fell within Lahore's territory, which extended to Fazilka's borders. The Kasur district was subsequently entrusted to Nihal Singh Atariwala.[4]

Attock annexed by Ranjit Singh

In December 1812, Jahandad Khan, governor of Attock, grew restless upon learning of the planned joint expedition to Kashmir. Anticipating he'd be the Wazir's next target after his brother's defeat, Jahandad Khan sought a deal with Ranjit Singh to surrender Attock. He sent confidential messengers to the Maharaja, requesting security against Kabul, a jagir in Punjab, and a substantial allowance. Ranjit Singh warmly received the agents, approved the proposal, and invited Jahandad Khan to meet him at Wazirabad

The terms were settled, and both parties appointed spies to report on the Wazir's Kashmir campaign. Before departing Rohtas, Ranjit Singh appointed Daya Singh commander of a strong contingent at Serai Kali, near Hasan Abdal, to occupy Attock Fort when offered. Another force under Bhayya Ram Singh Purabia was stationed at Hasan Abdal to reinforce Daya Singh. Devi Das, Mit Singh Bharania, and Faqir Aziz-ud-din were sent to Hasan Abdal to finalize negotiations,

In February 1813, Kashmir fell to the Wazir, and news reached Lahore and Attock simultaneously. Jahandad Khan contacted Daya Singh to take possession of Attock Fort. However, Aziz-ud-din's diplomatic party advised waiting for Diwan Mohkam Chand's safe return from the Pir Panjal mountains. On March 9, the three parties arrived at Attock, and Abdur Rahim relinquished the fort to Maharaja's officers. Jahandad Khan had already departed for Lahore

The annexation added 134 villages and significant resources to Ranjit Singh's kingdom, including grain, ammunition, tobacco, and rock salt. The Sikhs also captured 70 guns, mortars, and swivels. Ranjit Singh declined congratulations, anticipating an attack by Wazir Fatah Khan while returning from Kashmir to Kabul, Following the annexation, Qazi Ghulam Muhammad fled to the Khatak country under Firoz Khan. However, Arnir Singh Sandhanwalia restored his jagir and granted a new one worth Rs. 300 annually. Later, Ranjit Singh appointed him Vakil for Khataks and Yusafzais, a position he held until his death at the hands of a Nihang in 1842.[87]

The most significant encounters between the Sikhs in the command of the Maharaja and the Afghans were in 1813, 1823, 1834 and 1837.[7] In 1813, Ranjit Singh's general Dewan Mokham Chand led the Sikh forces against the Afghan forces of Shah Mahmud led by Fateh Khan Barakzai.[88] The Afghans lost their stronghold at Attock in that battle.

In 1813–14, Ranjit Singh's first attempt to expand into Kashmir was foiled by Afghan forces led by Azim Khan, due to a heavy downpour, the spread of cholera, and poor food supply to his troops.[citation needed]

Maharajah Ranjit Singh's conquest of Multan (1818)

Maharajah Ranjit Singh's conquest of Multan in 1818 was a strategic move, exploiting Muzaffar Khan's weakened resources due to annual exactions and ravages. The Kabul government's disorganization and Wazir Fatah Khan's absence provided an ideal opportunity. Ranjit Singh appointed Missar Diwan Chand, Commander-in-Chief, to lead 25,000 well-equipped troops, including horse and foot soldiers, and a strong artillery park.

Prince Kharak Singh, 16, was nominal head, while Diwan Chand held actual command. Key commanders included Dal Singh Naherna, Fatah Singh Ahluwalia, Dhanna Singh Malwai, Diwan Moti Ram, Diwan Ram Dayal, Jodh Singh Kalsia, and Hari Singh Nalwa. The Sikh army captured Khangarh and Muzaffargarh forts before besieging Multan.

Twelve batteries and trenches were deployed, but the Nawab's garrison resisted. Despite heavy losses, including 1,800 Sikh soldiers, Diwan Chand requested Ahmad Shah Durrani's zamzama gun. The gun's arrival led Ranjit Singh to offer Muzaffar Khan a jagir and governorship. Negotiations failed, and the zamzama gun breached the fort walls.

Sadhu Singh Akali's Nihangs led the final assault, killing Muzaffar Khan and most of his sons. Multan fell on June 29, 1818. Lahore and Amritsar celebrated with illuminations and offerings to holy shrines. The fort was sacked, yielding significant booty. Troops were ordered to return spoils to the State treasury. Reluctantly, soldiers, officers, and jagirdars surrendered approximately five lakhs of rupees worth of articles. Ranjit Singh compensated families of fallen soldiers and rewarded Diwan Chand with titles, jagir, and khilat.

Muzaffar Khan's sons received a jagir of Rs. 30,000 and a cash allowance for maintenance. Military officers were honored with khilms, jewelry, and cash. A contingent was sent to Shujabad, 38 km distant, another stronghold of Muzaffar Khan. It fell without resistance, yielding five cannons.[89]

The Conquest of Kashmir, 1919

In 1818, Maharajah Ranjit Singh conquered the Multan province, bolstering his confidence in his generals and soldiers. He then set his sights on Kashmir, particularly after Wazir Fatah Khan's death and Governor Azim Khan's departure. Azim Khan had withdrawn the best Afghan troops from Kashmir to establish himself in Kabul, leaving the region under Jabbar Khan's control.

The Afghan rule in Kashmir was deeply unpopular among both Hindus and Muslims. Ranjit Singh saw an opportunity and released Sultan Khan of Bhimbar from seven years' confinement in exchange for his cooperation in the impending invasion. However, Jabbar Khan discovered Pandit Birbaldhar's plans to persuade Ranjit Singh to conquer Kashmir and attacked Birbaldhar's house.

Birbaldhar's wife took her own life, while his son Raj Kak's bride was sent to Azim Khan in Kabul. Undeterred, Ranjit Singh planned to invade Kashmir, establishing his camp at Wazirabad. He appointed Missar Diwan Chand to lead the 12,000-strong army, divided into three columns, with Prince Kharak Singh and Hari Singh Nalwa providing support.

Diwan Chand was accompanied by Sultan Khan and guided by Birbaldhar through the Toshamaidan Pass. The army reached Rajauri in June 1819, prompting Raja Aghar Khan to flee. The Sikhs destroyed the fort, plundered the town, and installed Rahimullah Khan as the new Raja. Aghar Khan joined forces with Ruhullah Khan of Punchh and attacked the Sikhs in the Dhakideo and Maja passes but was repelled. Diwan Chand crossed the Pir Panjal range and descended into the valley at Serae Ali. Jabbar Khan awaited him at Shopian but was defeated in a sharp engagement on July 5, 1819.

Despite a brief moment of confusion during a rivulet crossing, the Sikh army rallied and decisively defeated Jabbar Khan once more. He fled to Muzaffarabad, then Peshawar, and eventually Kabul. The Sikh army entered Srinagar on July 15, 1819, marking the beginning of their rule in Kashmir. Dewan Moti Ram was appointed governor of Kashmir.[90]

Battle of Naushahra in 1823.

In 1823, the Sayyids and Mullas fueled the flames of resistance among the Yusafzais, urging them to expel the Sikhs from their territory. The tribal leaders, backed by Azim Khan, Afghanistan's Prime Minister, decided to engage in a fierce battle against the Sikhs. Azim Khan was displeased with his brother Yar Muhammad Khan, Governor of Peshawar, for submitting to Ranjit Singh, and thus declared a holy war against the Sikhs. This led to Kabul, Peshawar, and Hazara preparing for an all-out fight.

Maharaja Ranjit Singh swiftly responded by leading a robust army with heavy artillery from Lahore. He crossed the Indus River on March 13, 1823, and advanced to Naushahra. Jai Singh Atariwala, who had previously defected to Dost Muhammad Khan, sought pardon from the Maharaja and rejoined his forces. The Yusafzais and Khataks positioned themselves at Tihri, on the left bank of the Kabul River, just two kilometers from Naushahra. Azim Khan, with his formidable forces, set up camp on the right bank, a few kilometers from Tihri. His brothers, Jabbar Khan and Dost Muhammad Khan, rallied the tribals and took charge of leading them.

Ranjit Singh strategically divided his army into two divisions. One, led by himself, Missar Diwan Chand, Balbhadra Singh Gorkha, and Akali Phula Singh, confronted the Yusafzais and Khataks. The other, under Hari Singh Nalwa, Jamadar Khushhal Singh, Sher Singh, Budh Singh Sandhanwalia, and General Ventura, aimed to prevent Azim Khan from crossing the river and joining forces with the Ghazis. The intense bombardment forced the tribals to retreat from their position. As they descended, Akali Phula Singh spearheaded a fierce attack. The Ghazis suffered heavy losses, with no quarter given. Ranjit Singh personally led three charges, driving them back. The tribals fled, leaving 3,000 dead or wounded behind.[91]

The Sikhs also suffered significant losses, including notable commanders Akali Phula Singh and General Balbhadra Singh Gorkha, with around 2,000 men. Azim Khan fled to Peshawar and eventually Kabul, dying a month and a half later, broken-hearted and disgraced. The battle marked a significant milestone, establishing Sikh supremacy west of the Indus River, A gurdwara erected in honor of Akali Phula Singh, commemorating his bravery [92]

The 'Holy' War on the North-western Frontier: Fall of Syed Ahmed of Rai Bareli

Syed Ahmad, driven by a vision to restore an Islamic state in India, recognized jihad as the sole means to achieve this goal. To accomplish this, he sought to uproot both British and Sikh rule, focusing first on the lesser power, the Sikhs. This strategy aligned with British interests, as they sought to keep Ranjit Singh occupied in the northwest, preventing him from conquering Sind. Syed Ahmad spent a year and a half preparing for jihad at Rae Bareilly before departing on January 16, 1826, with 500-600 followers. Traveling through various regions, including Gwalior, Tonk, and Ajmer, he garnered support. In Afghanistan, however, he found the government and people unresponsive.

Undeterred, he established his headquarters at Naushahra in December 1826 and raised the green Muhammadi Jhanda banner. Four influential Peshawar chiefs, Yar Muhammad Khan, Sultan Muhammad Khan, Sayid Muhammad Khan, and Pir Muhammad Khan, backed Syed Ahmad's crusade. Other notable supporters included Mir Alam Khan of Bajaur, Fatah Khan of Panjtar, and Paindah Khan of Amb. Thousands of tribals flocked to his banner. Before engaging the Sikhs, Syed Ahmad issued a proclamation to Ranjit Singh outlining conditions for compliance.

When ignored, he prepared for war. His trusted lieutenants, Maulvis Abdul Hai, Muhammad Ismail Khan, and Baqar Ali, delivered impassioned speeches to secure men and resources. The Sikhs, led by Budh Singh Sandhanwalia, countered Syed Ahmad's advances. Budh Singh, a skilled fighter, had previously lost Maharaja Ranjit Singh's trust due to a thwarted plot to seize power. Despite this, Ranjit Singh valued his military prowess and stationed him in Hazara.

The Battle of Akora on December 21, 1826, marked the first significant clash. Syed Ahmad's forces launched a nighttime assault, catching the Sikhs off guard. Budh Singh swiftly regrouped and repelled the attack. Although victorious, he failed to pursue the enemy. The battle resulted in substantial losses for both sides: approximately 500 Sikhs and 82 of Syed Ahmad's men, including Maulvi Baqar Ali and Allahbakhsh Khan.

Syed Ahmad relocated to Sitana, where local chiefs, impressed by the Ghazis' bravery, joined his cause. A conference at Akora on January 11, 1827, solidified support for Syed Ahmad, declaring him Imam. His following swelled to 50,000, bolstered by Pathans and Barakzai chiefs. The subsequent Battle of Saidu or Pirpai in March 1827 saw Budh Singh's 10,000-strong Sikh force withstand intense assaults.

Through diplomacy, Budh Singh secured the neutrality of the Barakzai chief, then launched a decisive counterattack. Sikh artillery devastated the enemy, prompting flight. An estimated 6,000 Mujahidin were killed or wounded, with Syed Ahmad fleeing to the Swat hills. Ranjit Singh honored Budh Singh and other commanders for their victory.[93]

Syed Ahmad began to live with Fatah Khan of Panjtar, a fanatic and one of the bitterest enemies of the Sikhs. With his help, the Sayyid commenced coercing neighboring chiefs to support him fully in the Jihad against the Sikhs. Ahmad Khan of Hoti, who responded lukewarmly, was killed in action. The Sayyid brought the entire Yusafzai valley under his sway, subduing Mir Babu Khau of Sadhum.

The Sayyid made extensive tours of Buner and Swat, exhorting the people to unite and end Sikh rule. He invited Afridis, Mohmands, and Khalils to join him in the Jihad. Maulvi Ismail focused on Hazara, gaining support from prominent Khans, including Sarhuland Khan of Tanawal, Habibullah Khan of Swat, Sultan Zabardast Khan of Muzaffarabad, Sultan Najaf Khan of Khatur, Khan Abdul Ghafur Khan of Agror, Nasir Khan of Nandhar, and Paindah Khan of Amb.

In mid-1827, two fierce skirmishes were fought between the Sayyid and the Sikhs at Damgala and Shinkiari. Having secured men and money, the Sayyid decided to deal with the Barakzai chiefs of Peshawar in 1828. Yar Muhammad Khan intercepted the Sayyid's forces at Utmanzai, situated on the left bank of the Kabul river. The battle lasted the whole day, with some Khans defecting to Yar Muhammad Khan. The Sayyid took flight in the night.

Having failed at Peshawar, Syed Ahmad planned to seize Attock fort from the Sikhs. Khadi Khan of Hund secretly alerted the Sikh commander, and the plan fell through. The Sayyid attacked the villageHaidru, massacring its inhabitants. General Ventura decided to surprise the Sayyid by delivering an attack on his headquarters at Panjtar. The Mujahidin took advantage of the terrain, forcing Ventura to withdraw without achieving anything. Syed Ahmad punished Khadi Khan of Hund for secretly allying with the Sikhs. In the battle of Hund, Khadi Khan was defeated and killed.

Yar Muhammad Khan, frightened by Khadi Khan's fate, decided to forestall the Sayyid. The opposing forces met at Zaidah, where Yar Muhammad Khan was seriously wounded and later expired. The Sayyid resolved to turn the Sikhs out of Hazara, combining forces with Paindah Khan. A fierce battle was fought at Phulra, where the Sikhs employed "Hit and Run" tactics. The Sayyid's nephew, Sayyid Ahmad Ali Shah, and Mir Faiz Ali of Gorakhpur were killed.

In 1830, Syed Ahmad subdued Sultan Muhammad Khan, ruler of Peshawar, reaching the zenith of his power. He introduced reforms according to Shariat, enforcing payment of ashar (tithe), prohibiting the sale of daughters, and denouncing pilgrimage to saints' tombs.The Yusafzais and Khataks opposed these reforms, resenting the loss of money and the prohibition of selling girls. A secret council plotted to destroy the Sayyid's followers, massacring several thousand. The Sayyid escaped to Tahkot and later established his headquarters at Rajduwari..[94] Here's a detailed account of the events surrounding the Battle of Balakot:

In May 1831, Kanwar Sher Singh led a formidable force of approximately 5,000 troops, accompanied by trusted commanders Pratab Singh Atariwala and Ratan Singh Garjakhia, to the region of Balakot. Their mission was to confront Sayyid Ahmad, a prominent Islamic leader who had been waging a jihad against the Sikh Empire. The Sayyid's forces, largely comprising peasants, numbered between 2,000 and 3,000. The Sikhs strategically encircled Balakot, gradually tightening their grip on the besieged area. As they advanced, they drew their swords, cutting down the peasant-soldiers with devastating efficiency. Sayyid Ahmad was fatally shot, and his body, along with those of his fallen Ghazis, was set ablaze. The Sikhs also claimed significant spoils, including tents, swivels, swords, horses, and an elephant..[95]

The battle resulted in a crushing defeat for the Sayyid's forces, with approximately 500 followers killed, including key leaders Maulvi Ismail and Bahram Khan. The Sikhs emerged victorious, and the news of their triumph was met with jubilation. Maharaja Ranjit Singh rewarded the messenger with gold bracelets, a turban, and shawls, and dispatched a letter of appreciation to Sher Singh, promising an additional jagir worth Rs. 50,000. To commemorate the victory, the Governor of Gobindgarh, Faqir Imam-ud-din, was instructed to fire an 11-gun salute and illuminate the city of Amritsar..[96]

Annexation of Peshawar, 1834

In 1833, Lord William Bentinck, the Governor-General, granted Shah Shuja-ul-Mulk permission to assemble an army to reclaim his lost throne in Kabul. This led to a treaty between Shah Shuja-ul-Mulk and Maharaja Ranjit Singh, where the latter agreed to assist the Shah in exchange for renouncing his claims on Peshawar, Trans-Indus territory, Attock, Multan, and Kashmir, which were under the Maharaja's control.

However, Maharaja Ranjit Singh was wary of the Shah's intentions, as he had openly declared that agreements were meaningless and only power mattered. Moreover, the Maharaja feared that Sultan Muhammad Khan and his brothers might pledge allegiance to the Shah if he succeeded. Sultan Muhammad Khan only paid tribute when faced with military action, and Ost Muhammad considered Peshawar crucial for his kingdom's preservation.

To mitigate these risks, Maharaja Ranjit Singh decided to bring Peshawar under his direct control before the impending conflict between Shah Shuja-ul-Mulk and Ost Muhammad Khan. He ordered Hari Singh Nalwa to proceed to Peshawar from Yusafzai Hills and sent Prince Nau Nihal Singh, Ventura, and Court from Lahore with 9,000 soldiers. They crossed the Indus in April 1834, prompting Sultan Muhammad Khan to flee to Kabul and join his brother Ost Muhammad Khan.

With Shah Shuja-ul-Mulk in Kandhar and Ost Muhammad Khan preparing to fight him, the timing was ideal. Maharaja Ranjit Singh established his administration in Peshawar in May 1834, appointing Hari Singh Nalwa as governor. Following Ost Muhammad Khan's victory over Shah Shuja-ul-Mulk in June 1834, Hari Singh commanded a 12,000-strong force to maintain law and order in the region west of the Indus.[97]

In 1835, the Afghans and Sikhs met again at the Standoff at the Khyber Pass, however it ended without a battle.[98]

In 1837, the Battle of Jamrud, became the last confrontation between the Sikhs led by him and the Afghans, which displayed the extent of the western boundaries of the Sikh Empire.[99][100]

On 25 November 1838, the two most powerful armies on the Indian subcontinent assembled in a grand review at Ferozepore as Ranjit Singh, the Maharajah of the Punjab brought out the Dal Khalsa to march alongside the sepoy troops of the East India Company and the British troops in India.[101] In 1838, he agreed to a treaty with the British viceroy Lord Auckland to restore Shah Shoja to the Afghan throne in Kabul. In pursuance of this agreement, the British army of the Indus entered Afghanistan from the south, while Ranjit Singh's troops went through the Khyber Pass and took part in the victory parade in Kabul.[102][103]

Geography of the Sikh Empire

The Sikh Empire, also known as the Sikh Raj and Sarkar-a-Khalsa,[104] was in the Punjab region, the name of which means "the land of the five rivers". The five rivers are the Beas, Ravi, Sutlej, Chenab and Jhelum, all of which are tributaries of the river Indus.[105]

The geographical reach of the Sikh Empire under Singh included all lands north of Sutlej River, and south of the high valleys of the northwestern Himalayas. The major towns at the time included Srinagar, Attock, Peshawar, Bannu, Rawalpindi, Jammu, Gujrat, Sialkot, Kangra, Amritsar, Lahore and Multan.[44][106]

Muslims formed around 70%, Hindus formed around 24%, and Sikhs formed around 6–7% of the total population living in Singh's empire[107]: 2694

Governance

Ranjit Singh allowed men from different religions and races to serve in his army and his government in various positions of authority.[108] His army included a few Europeans, such as the Frenchman Jean-François Allard, though Singh maintained a policy of refraining from recruiting Britons into his service, aware of British designs on the Indian subcontinent.[109] Despite his recruitment policies, he did maintain a diplomatic channel with the British; in 1828, he sent gifts to George IV and in 1831, he sent a mission to Simla to confer with the British Governor General, William Bentinck, which was followed by the Ropar Meeting;[110] while in 1838, he cooperated with them in removing the hostile Islamic Emir in Afghanistan.[100]

Religious policies

As consistent with many Punjabis of that time, Ranjit Singh was a secular king[113] and followed the Sikh path.[114] His policies were based on respect for all communities, Hindu, Sikh and Muslim.[70] A devoted Sikh, Ranjit Singh restored and built historic Sikh Gurdwaras – most famously, the Harmandir Sahib, and used to celebrate his victories by offering thanks at the Harmandir. He also joined the Hindus in their temples out of respect for their sentiments.[70] The veneration of cows was promoted and cow slaughter was punishable by death under his rule.[115][116] He ordered his soldiers to neither loot nor molest civilians.[117]

He built several gurdwaras, Hindu temples and even mosques, and one in particular was Mai Moran Masjid, built at the behest of his beloved Muslim wife, Moran Sarkar.[118] The Sikhs led by Singh never razed places of worship to the ground belonging to the enemy.[119] However, he did convert Muslim mosques into other uses. For example, Ranjit Singh's army desecrated Lahore's Badshahi Mosque and converted it into an ammunition store,[120] and horse stables.[121] Lahore's Moti Masjid (Pearl Mosque) was converted into "Moti Mandir" (Pearl Temple) by the Sikh army,[121][122] and Sonehri Mosque was converted into a Sikh Gurdwara, but upon the request of Sufi Fakir (Satar Shah Bukhari), Ranjit Singh restored the latter to a mosque.[123] Lahore's Begum Shahi Mosque was also used as a gunpowder factory, earning it the nickname Barudkhana Wali Masjid, or "Gunpowder Mosque."[124]

Singh's sovereignty was accepted by Afghan and Punjabi Muslims, who fought under his banner against the Afghan forces of Nadir Shah and later Azim Khan. His court was ecumenical in composition: his prime minister, Dhian Singh, was a Hindu (Dogra); his foreign minister, Fakir Azizuddin, was a Muslim; and his finance minister, Dina Nath, was also a Hindu (Brahmin). Artillery commanders such as Mian Ghausa were also Muslims. There were no forced conversions in his time. His wives Bibi Mohran, Gilbahar Begum retained their faith and so did his Hindu wives. He also employed and surrounded himself with astrologers and soothsayers in his court.[125]

Ranjit Singh had also abolished the gurmata and provided significant patronage to the Udasi and Nirmala sect, leading to their prominence and control of Sikh religious affairs.[130]

Administration

Khalsa Army

The army under Ranjit Singh was not limited to the Sikh community. The soldiers and troop officers included Sikhs, but also included Hindus, Muslims and Europeans.[131] Hindu Brahmins and people of all creeds and castes served his army,[132][133] while the composition in his government also reflected a religious diversity.[131][134] His army included Polish, Russian, Spanish, Prussian and French officers.[11] In 1835, as his relationship with the British warmed up, he hired a British officer named Foulkes.[11]

However, the Khalsa army of Ranjit Singh reflected the regional population, and as he grew his army, he dramatically increased the Rajputs and the Sikhs who became the predominant members of his army.[10] In the Doaba region his army was composed of the Jat Sikhs, in Jammu and northern Indian hills it was Hindu Rajputs, while relatively more Muslims served his army in the Jhelum river area closer to Afghanistan than other major Panjab rivers.[135]

Reforms

Ranjit Singh changed and improved the training and organisation of his army. He reorganised responsibility and set performance standards in logistical efficiency in troop deployment, manoeuvre, and marksmanship.[134] He reformed the staffing to emphasise steady fire over cavalry and guerrilla warfare, and improved the equipment and methods of war. The military system of Ranjit Singh combined the best of both old and new ideas. He strengthened the infantry and the artillery.[10] He paid the members of the standing army from treasury, instead of the Mughal method of paying an army with local feudal levies.[10]

While Ranjit Singh introduced reforms in terms of training and equipment of his military, he failed to reform the old Jagirs (Ijra) system of Mughal middlemen.[136][137] The Jagirs system of state revenue collection involved certain individuals with political connections or inheritance promising a tribute (nazarana) to the ruler and thereby gaining administrative control over certain villages, with the right to force collect customs, excise and land tax at inconsistent and subjective rates from the peasants and merchants; they would keep a part of collected revenue and deliver the promised tribute value to the state.[136][138][139] These Jagirs maintained independent armed militia to extort taxes from the peasants and merchants, and the militia was prone to violence.[136] This system of inconsistent taxation with arbitrary extortion by militia, continued the Mughal tradition of ill treatment of peasants and merchants throughout the Sikh Empire, and is evidenced by the complaints filed to Ranjit Singh by East India Company officials attempting to trade within different parts of the Sikh Empire.[136][137]

According to historical records, Sunit Singh, Ranjit Singh's reforms focused on the military that would allow new conquests, but not towards the taxation system to end abuse, nor on introducing uniform laws in his state or improving internal trade and empowering the peasants and merchants.[136][137][138] This failure to reform the Jagirs-based taxation system and economy, in part led to a succession power struggle and a series of threats, internal divisions among Sikhs, major assassinations and coups in the Sikh Empire in the years immediately after the death of Ranjit Singh;[140] an easy annexation of the remains of the Sikh Empire into British India followed, with the colonial officials offering the Jagirs better terms and the right to keep the system intact.[141][142][143]

Infrastructure investments

Ranjit Singh ensured that Panjab manufactured and was self-sufficient in all weapons, equipment and munitions his army needed.[11] His government invested in infrastructure in the 1800s and thereafter, established raw materials mines, cannon foundries, gunpowder and arms factories.[11] Some of these operations were owned by the state, and others were operated by private Sikh operatives.[11]

However, Ranjit Singh did not make major investments in other infrastructure such as irrigation canals to improve the productivity of land and roads. The prosperity in his Empire, in contrast to the Mughal-Sikh wars era, largely came from the improvement in the security situation, reduction in violence, reopened trade routes and greater freedom to conduct commerce.[144]

Muslim accounts

The mid 19th-century Muslim historians, such as Shahamat Ali who experienced the Sikh Empire first hand, presented a different view on Ranjit Singh's Empire and governance.[145][146] According to Ali, Ranjit Singh's government was despotic, and he was a mean monarch in contrast to the Mughals.[145] The initial momentum for the Empire building in these accounts is stated to be Ranjit Singh led Khalsa army's "insatiable appetite for plunder", their desire for "fresh cities to pillage", and eliminating the Mughal era "revenue intercepting intermediaries between the peasant-cultivator and the treasury".[140]

According to Ishtiaq Ahmed, Ranjit Singh's rule led to further persecution of Muslims in Kashmir, expanding[clarification needed] the previously selective persecution of Shia Muslims and Hindus by Afghan Sunni Muslim rulers between 1752 and 1819 before Kashmir became part of his Sikh Empire.[147] Bikramjit Hasrat describes Ranjit Singh as a "benevolent despot".[148] The Muslim accounts of Ranjit Singh's rule were questioned by Sikh historians of the same era. For example, Ratan Singh Bhangu in 1841 wrote that these accounts were not accurate, and according to Anne Murphy, he remarked, "when would a Musalman praise the Sikhs?"[149] In contrast, the colonial era British military officer Hugh Pearse in 1898 criticised Ranjit Singh's rule, as one founded on "violence, treachery and blood".[150] Sohan Seetal disagrees with this account and states that Ranjit Singh had encouraged his army to respond with a "tit for tat" against the enemy, violence for violence, blood for blood, plunder for plunder.[151]

Decline

Singh made his empire and the Sikhs a strong political force, for which he is deeply admired and revered in Sikhism. After his death, the empire failed to establish a lasting structure for Sikh government or stable succession, and the Sikh Empire began to decline. The British and Sikh Empire fought two Anglo-Sikh wars with the second ending the reign of the Sikh Empire.[152] Sikhism itself did not decline.[153]

Clive Dewey has argued that the decline of the empire after Singh's death owes much to the jagir-based economic and taxation system which he inherited from the Mughals and retained. After his death, a fight to control the tax spoils emerged, leading to a power struggle among the nobles and his family from different wives. This struggle ended with a rapid series of palace coups and assassinations of his descendants, and eventually the annexation of the Sikh Empire by the British.[140]

Death and legacy

Death

In the 1830s, Ranjit Singh suffered from numerous health complications as well as a stroke, which some historical records attribute to alcoholism and a failing liver.[44][154] According to the chronicles of Ranjit Singh's court historians and the Europeans who visited him, Ranjit Singh took to alcohol and opium, habits that intensified in the later decades of his life.[155][156][157] He died in his sleep on 27 June 1839.[48][102] According to William Dalrymple, Ranjit Singh had been washed with water from the Ganges, paid homage to the Guru Granth Sahib, and was fixated on an image of Vishnu and Lakshmi just before his death.[158]

Four of his Hindu wives- Mehtab Devi (Guddan Sahiba), daughter of Raja Sansar Chand, Rani Har Devi, the daughter of Chaudhri Ram, a Saleria Rajput, Rani Raj Devi, daughter of Padma Rajput and Rani Rajno Kanwar, daughter of Sand Bhari along with seven Hindu concubines with royal titles committed sati by voluntarily placing themselves onto his funeral pyre as an act of devotion.[48][159]

Singh is remembered for uniting Sikhs and founding the prosperous Sikh Empire. He is also remembered for his conquests and building a well-trained, self-sufficient Khalsa army to protect the empire.[160] He amassed considerable wealth, including gaining the possession of the Koh-i-Noor diamond from Shuja Shah Durrani of Afghanistan, which he left to Jagannath Temple in Puri, Odisha in 1839.[161][162]

Gurdwaras

Perhaps Singh's most lasting legacy was the restoration and expansion of the Harmandir Sahib, the most revered Gurudwara of the Sikhs, which is now known popularly as the "Golden Temple".[163] Much of the present decoration at the Harmandir Sahib, in the form of gilding and marblework, was introduced under the patronage of Singh, who also sponsored protective walls and a water supply system to strengthen security and operations related to the temple.[13] He also directed the construction of two of the most sacred Sikh temples, being the birthplace and place of assassination of Guru Gobind Singh – Takht Sri Patna Sahib and Takht Sri Hazur Sahib, respectively – whom he much admired.[citation needed] The nine-storey tower of Gurdwara Baba Atal was constructed during his reign.[164]

Memorials and museums

- Samadhi of Ranjit Singh in Lahore, Pakistan, marks the place where Singh was cremated, and four of his queens and seven concubines committed sati.[165][166]

- On 20 August 2003, a 22-foot-tall bronze statue of Singh was installed in the Parliament of India.[167]

- A museum at Ram Bagh Palace in Amritsar contains objects related to Singh, including arms and armour, paintings, coins, manuscripts, and jewellery. Singh had spent much time at the palace in which it is situated, where a garden was laid out in 1818.[168]

- On 27 June 2019, a nine-foot bronze statue of Singh was unveiled at the Haveli Maharani Jindan, Lahore Fort at his 180th death anniversary.[169] It has been vandalised several times since, specifically by members of the Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan.[170][171]

Exhibitions

- Ranjit Singh: Sikh, Warrior, King (The Wallace Collection, London; 10 April–20 October 2024) – co-curated by the Wallace Collection's director, Xavier Bray, and scholar of Sikh art, Davinder Singh Toor.[172]

Crafts

In 1783, Ranjit Singh established a crafts colony of Thatheras near Amritsar and encouraged skilled metal crafters from Kashmir to settle in Jandiala Guru.[173] In the year 2014, this traditional craft of making brass and copper products was enlisted on the List of Intangible Cultural Heritage by UNESCO.[174] The Government of Punjab is now working under Project Virasat to revive this craft.[175]

Recognition

In 2020, Ranjit Singh was named as "Greatest Leader of All Time" in a poll conducted by 'BBC World Histories Magazine'.[176][177][178]

In popular culture

- Maharaja Ranjit Singh, a documentary film directed by Prem Prakash covers his rise to power and his reign. It was produced by the Government of India's Films Division.[179]

- In 2010, a TV series titled Maharaja Ranjit Singh aired on DD National based on his life which was produced by Raj Babbar's Babbar Films Private Limited. He was portrayed by Ejlal Ali Khan

- Maharaja: The Story of Ranjit Singh (2010) is an Indian Punjabi-language animated film directed by Amarjit Virdi.[180]

- A teenage Ranjit was portrayed by Damanpreet Singh in the 2017 TV series titled Sher-e-Punjab: Maharaja Ranjit Singh. It aired on Life OK produced by Contiloe Entertainment.

See also

- Baradari of Ranjit Singh

- History of Punjab

- Charat Singh

- Hari Singh Nalwa

- List of generals of Ranjit Singh

- Koh-i-Noor

- Battle of Balakot[181][182][183]

Notes

References

- ^ https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/hindi-english/%E0%A4%B8%E0%A4%B0%E0%A4%95%E0%A4%BE%E0%A4%B0#:~:text=%2Fsarak%C4%81ra%2F,are%20responsible%20for%20governing%20it. [bare URL]

- ^ A history of the Sikhs by Kushwant Singh, Volume I (p. 195)

- ^ S.R. Bakshi, Rashmi Pathak (2007). "1-Political Condition". In S.R. Bakshi, Rashmi Pathak (ed.). Studies in Contemporary Indian History – Punjab Through the Ages Volume 2. Sarup & Sons, New Delhi. p. 2. ISBN 978-81-7625-738-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Singh, Kushwant (2011). "Ranjit Singh (1780–1839)". In Singh, Harbans (ed.). The Encyclopedia Of Sikhism. Vol. III M–R (Third ed.). Punjabi University Patiala. pp. 479–487. ISBN 978-8-1-7380-349-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Khushwant Singh (2008). Ranjit Singh. Penguin Books. pp. 9–14. ISBN 978-0-14-306543-2.

- ^ Chisholm 1911.

- ^ a b Grewal, J. S. (1990). "Chapter 6: The Sikh empire (1799–1849)". The Sikh empire (1799–1849). The New Cambridge History of India. Vol. The Sikhs of the Punjab. Cambridge University Press. Archived from the original on 16 February 2012. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- ^ Sarkar, Sir Jadunath (1960). Military History of India. Orient Longmans. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-86125-155-1.

- ^ Patwant Singh (2008). Empire of the Sikhs: The Life and Times of Maharaja Ranjit Singh. Peter Owen. pp. 113–124. ISBN 978-0-7206-1323-0.

- ^ a b c d Teja Singh; Sita Ram Kohli (1986). Maharaja Ranjit Singh. Atlantic Publishers. pp. 65–68.

- ^ a b c d e f Kaushik Roy (2011). War, Culture and Society in Early Modern South Asia, 1740–1849. Routledge. pp. 143–144. ISBN 978-1-136-79087-4.

- ^ Kaushik Roy (2011). War, Culture and Society in Early Modern South Asia, 1740–1849. Routledge. pp. 143–147. ISBN 978-1-136-79087-4.

- ^ a b Jean Marie Lafont (2002). Maharaja Ranjit Singh: Lord of the Five Rivers. Oxford University Press. pp. 95–96. ISBN 978-0-19-566111-8.

- ^ Kerry Brown (2002). Sikh Art and Literature. Routledge. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-134-63136-0.

- ^ Arora, A. C. (1984). "Ranjit Singh's Relations with the Jind State". In Singh, Fauja; Arora, A. C. (eds.). Maharaja Ranjit Singh: Politics, Society, and Economy. Punjabi University. p. 86. ISBN 978-81-7380-772-5. OCLC 557676461.

Even before the birth of Ranjit Singh, cordial relations had been established between the Sukarchakia Misal and the Phulkian House of Jind. ... the two Sikh Jat chiefships had cultivated intimate relationship with each other by means of a matrimonial alliance. Maha Singh, the son of the founder of Sukarchakia Misal, Charat Singh, was married to Raj Kaur, the daughter of the founder of the Jind State, Gajpat Singh. The marriage was celebrated in 1774 at Badrukhan, then capital of Jind1, with pomp and grandeur worthy of the two chiefships. ... Ranjit Singh was the offspring of this wedlock.

- ^ Singh, Patwant; Rai, Jyoti M. (2008). Empire of the Sikhs: the life and times of Maharaja Ranjit Singh. London: Peter Owen. p. 69. ISBN 978-0720613230.

- ^ McLeod, W. H. (2009). The A to Z of Sikhism. Scarecrow Press. p. 172. ISBN 978-0810863446.

Sikhs remember Maharaja Ranjit Singh with respect and affection as their greatest ruler. Ranjit Singh was a Sansi and this identity has led some to claim that his caste affiliation was with the low-caste Sansi tribe of the same name. A much more likely theory is that he belonged to the Jat got that used the same name. The Sandhanvalias belonged to the same got.

- ^ Singh, Birinder Pal (2012). 'Criminal' Tribes of Punjab. Taylor & Francis. p. 114. ISBN 978-1136517860.

Ibbetson and Rose and later, Bedi, had clarified that the Sansis should not be confused with a Jat (Jutt) clan named Sansi to which perhaps Maharaja Ranjit Singh also belonged.

- ^ Patwant Singh (2008). Empire of the Sikhs: The Life and Times of Maharaja Ranjit Singh. Peter Owen. pp. 58–59. ISBN 978-0-7206-1323-0.

- ^ Patwant Singh (2008). Empire of the Sikhs: The Life and Times of Maharaja Ranjit Singh. Peter Owen. pp. 56–57. ISBN 978-0-7206-1323-0.

- ^ a b c Jean Marie Lafont (2002). Maharaja Ranjit Singh: Lord of the Five Rivers. Oxford University Press. pp. 33–34, 15–16. ISBN 978-0-19-566111-8.

- ^ Khushwant Singh (2008). Ranjit Singh. Penguin Books. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-14-306543-2.

- ^ a b c Khushwant Singh (2008). Ranjit Singh. Penguin Books. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-0-14-306543-2.

- ^ a b Atwal, Priya (2020). Royals and Rebels. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780197548318.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-754831-8.

- ^ Bhatia, Sardar Singh (2011). "Mahitab Kaur (d, 1813)". In Singh, Harbans (ed.). The Encyclopedia Of Sikhism. Vol. III M–R (3rd ed.). Punjabi University Patiala. p. 19. ISBN 978-8-1-7380-349-9.

- ^ a b Khushwant Singh (2008). Ranjit Singh. Penguin Books. pp. 300–301 footnote 35. ISBN 978-0-14-306543-2.

- ^ Atwal, Priya (2020). Royals and Rebels: The Rise and Fall of the Sikh Empire. C. Hurst (Publishers) Limited. ISBN 978-1-78738-308-1.

- ^ Vaḥīduddīn, Faqīr Sayyid (2001). The real Ranjit Singh. Publication Bureau, Punjabi University. ISBN 81-7380-778-7. OCLC 52691326.

- ^ "Mahanian Koharan Tehsil .Amritsar District .AmritsarState .Punjab". 17 December 2020 – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ Yudhvir Rana (1 May 2015). "Descendants of Maharaja Ranjit Singh stakes claim on Gobindgarh Fort". The Times of India. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- ^ Yudhvir Rana (18 August 2021). "Seventh generation descendent of Maharaja Ranjit Singh writes to Imran". The Times of India. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- ^ "Tuberculosis: Poor Awareness Leads to Poor Control". Journal of Sheikh Zayed Medical College. 11 (3): 1–2. 2021. doi:10.47883/jszmc.v11i03.158. ISSN 2305-5235. S2CID 236800828.

- ^ Journal of Sikh Studies. Department of Guru Nanak Studies, Guru Nanak Dev University. 2001.

- ^ a b Atwal, Priya (2021). Royals and Rebels: The Rise and Fall of the Sikh Empire. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-756694-7.

- ^ a b "Postscript: Maharaja Duleep Singh", Emperor of the Five Rivers, I.B. Tauris, 2017, doi:10.5040/9781350986220.0008, ISBN 978-1-78673-095-4

- ^ Tibbetts, Jann (2016). 50 Great Military Leaders of All Time. VIJ Books (India) PVT Limited. ISBN 978-9386834195.

- ^ Bhatia, Sardar Singh (2011). "Raj Kaur (d. 1838)". In Singh, Harbans (ed.). The Encyclopedia Of Sikhism. Vol. III M–R (3rd ed.). Punjabi University Patiala. p. 443. ISBN 978-8-1-7380-349-9.

- ^ Khushwant Singh (1962). Ranjit Singh Maharajah Of The Punjab 1780–1839. Servants of Knowledge. George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

- ^ Fakir, Syed Waheeduddin; Vaḥīduddīn, Faqīr Sayyid (1965). The Real Ranjit Singh. Lion Art Press.

- ^ Sood, D. R. (1981). Ranjit Singh. National Book Trust. OCLC 499465766.