Flags of the Confederate States of America

This article contains too many or overly lengthy quotations. (July 2022) |

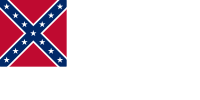

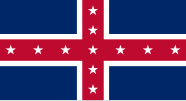

First national flag of the Confederate States of America. | |

| "The Stars and Bars" | |

| Use | National flag |

|---|---|

| Proportion | 5:9 |

| Adopted | March 4, 1861 (first 7-star version) December 10, 1861 (final 13-star version) |

| Design | Three horizontal stripes of equal height, alternating red and white, with a blue square two-thirds the height of the flag as the canton. Inside the canton are seven, eleven, or thirteen white five-pointed stars of equal size, arranged in a circle and pointing outward. |

| Designed by | Nicola Marschall |

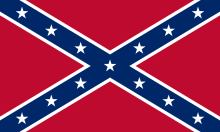

| "The Stainless Banner"[a] | |

The second national flag of the Confederate States of America | |

| Use | National flag |

| Proportion | 1:2[b] |

| Adopted | May 1, 1863 |

| Design | A white rectangle two times as wide as it is tall, a red quadrilateral in the canton, inside the canton is a blue saltire with white outlining, with thirteen white five-pointed stars of equal size inside the saltire. |

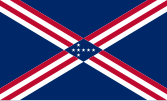

| "The Blood-Stained Banner" | |

The third national flag of the Confederate States of America. | |

| Use | National flag |

| Proportion | 2:3 |

| Adopted | March 4, 1865 |

| Design | A white rectangle, one-and-a-half times as wide as it is tall, a red vertical stripe on the far right of the rectangle, a red quadrilateral in the canton, inside the canton is a blue saltire with white outlining, with thirteen white five-pointed stars of equal size inside the saltire.[c] |

| Designed by | Maj. Arthur L. Rogers[13] |

The flags of the Confederate States of America have a history of three successive designs during the American Civil War. The flags were known as the "Stars and Bars", used from 1861 to 1863; the "Stainless Banner", used from 1863 to 1865; and the "Blood-Stained Banner", used in 1865 shortly before the Confederacy's dissolution. A rejected national flag design was also used as a battle flag by the Confederate Army and featured in the "Stainless Banner" and "Blood-Stained Banner" designs. Although this design was never a national flag, it is the most commonly recognized symbol of the Confederacy.

Since the end of the Civil War, private and official use of the Confederate flags, particularly the battle flag, has continued amid philosophical, political, cultural, and racial controversy in the United States. These include flags displayed in states; cities, towns and counties; schools, colleges and universities; private organizations and associations; and individuals. The battle flag was also featured in the state flags of Georgia and Mississippi, although it was removed by Georgia in 2003 and Mississippi in 2020. However, the new design of the Georgia flag still references the original "Stars and Bars" iteration of the Georgia flag. After the Georgia flag was changed in 2001, the city of Trenton, Georgia, has used a flag design nearly identical to the previous version with the battle flag.

It is estimated that 500–544 flags were captured during the civil war by the Union. The flags were sent to the War Department in Washington.[14][15]

First flag: the "Stars and Bars" (1861–1863)

[edit]The Confederacy's first official national flag, often called the Stars and Bars, flew from March 4, 1861, to May 1, 1863. It was designed by Prussian-American artist Nicola Marschall in Marion, Alabama, and is said to resemble the Flag of Austria, with which Marschall would have been familiar.[16][d] The original version of the flag featured a circle of seven white stars in the navy-blue canton, representing the seven states of the South that originally composed the Confederacy: South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas. The "Stars and Bars" flag was adopted on March 4, 1861, in the first temporary national capital of Montgomery, Alabama, and raised over the dome of that first Confederate capitol. Marschall also designed the Confederate army uniform.[19]

A monument that was in Louisburg, North Carolina, claims the "Stars and Bars" "was designed by a son of North Carolina / Orren Randolph Smith / and made under his direction by / Catherine Rebecca (Murphy) Winborne. / Forwarded to Montgomery, Ala. Feb 12, 1861, / Adopted by the Provisional Congress March 4, 1861".[20]

One of the first acts of the Provisional Confederate Congress was to create the Committee of the Flag and Seal, chaired by William Porcher Miles, a Democratic congressman, and Fire-Eater from South Carolina. The committee asked the public to submit thoughts and ideas on the topic and was, as historian John M. Coski puts it, "overwhelmed by requests not to abandon the 'old flag' of the United States." Miles had already designed a flag that later became known as the Confederate Battle Flag, and he favored his flag over the "Stars and Bars" proposal. But given the popular support for a flag similar to the U.S. flag ("the Stars and Stripes" – originally established and designed in June 1777 during the Revolutionary War), the "Stars and Bars" design was approved by the committee.[21]

As the Confederacy grew, so did the numbers of stars: two were added for Virginia and Arkansas in May 1861, followed by two more representing Tennessee and North Carolina in July, and finally two more for Missouri and Kentucky.

When the American Civil War broke out, the "Stars and Bars" confused the battlefield at the First Battle of Bull Run because of its similarity to the U.S. (or Union) flag, especially when it was hanging limply on its flagstaff.[22] The "Stars and Bars" was also criticized on ideological grounds for its resemblance to the U.S. flag. Many Confederates disliked the Stars and Bars, seeing it as symbolic of a centralized federal power against which the Confederate states claimed to be seceding.[23] As early as April 1861, a month after the flag's adoption, some were already criticizing the flag, calling it a "servile imitation" and a "detested parody" of the U.S. flag.[3] In January 1862, George William Bagby, writing for the Southern Literary Messenger, wrote that many Confederates disliked the flag. "Everybody wants a new Confederate flag," Bagby wrote. "The present one is universally hated. It resembles the Yankee flag, and that is enough to make it unutterably detestable." The editor of the Charleston Mercury expressed a similar view: "It seems to be generally agreed that the 'Stars and Bars' will never do for us. They resemble too closely the dishonored 'Flag of Yankee Doodle' ... we imagine that the 'Battle Flag' will become the Southern Flag by popular acclaim." William T. Thompson, the editor of the Savannah-based Daily Morning News also objected to the flag,[6] due to its aesthetic similarity to the U.S. flag, which for some Confederates had negative associations with emancipation and abolitionism. Thompson stated in April 1863 that he disliked the adopted flag "on account of its resemblance to that of the abolition despotism against which we are fighting."[1][4][5][7]

Over the course of the flag's use by the CSA, additional stars were added to the canton, eventually bringing the total number to thirteen-a reflection of the Confederacy's claims of having admitted the border states of Kentucky and Missouri, where slavery was still widely practiced.[e][24] The first showing of the 13-star flag was outside the Ben Johnson House in Bardstown, Kentucky; the 13-star design was also in use as the Confederate navy's battle ensign.[citation needed]

Second flag: the "Stainless Banner" (1863–1865)

[edit]

|

|

|

|

|

| Second national flag (May 1, 1863 – March 4, 1865), 2:1 ratio | Second national flag (May 1, 1863 – March 4, 1865) as commonly manufactured, with a 3:2 ratio | A 12-star variant of the Stainless Banner produced in Mobile, Alabama | Variant captured following the Battle of Painesville, 1865 | Garrison Flag of Fort Fisher, the "Southern Gibraltar" |

Many different designs were proposed during the solicitation for a second Confederate national flag, nearly all based on the Battle Flag. By 1863, it had become well-known and popular among those living in the Confederacy. The Confederate Congress specified that the new design be a white field "...with the union (now used as the battle flag) to be a square of two-thirds the width of the flag, having the ground red; thereupon a broad saltire of blue, bordered with white, and emblazoned with mullets or five-pointed stars, corresponding in number to that of the Confederate States."[11]

The flag is also known as the Stainless Banner, and the matter of the person behind its design remains a point of contention. On April 23, 1863, the Savannah Morning News editor William Tappan Thompson, with assistance from William Ross Postell, a Confederate blockade runner, published an editorial championing a design featuring the battle flag on a white background he referred to later as "The White Man's Flag", a name which never caught on.[6] In explaining the white background of his design, Thompson wrote, "As a people, we are fighting to maintain the Heaven-ordained supremacy of the white man over the inferior or colored race; a white flag would thus be emblematical of our cause." Most contemporary interpretations of the white area on the flag hold that it represented the purity of the secessionist cause.[25][3][10] In a letter to Confederate Congressman C. J. Villeré, dated April 24, 1863, a design similar to the flag which was eventually created was proposed by General P. G. T. Beauregard, "whose earlier penchant for practicality had established the precedent for visual distinctiveness on the battlefield, proposed that 'a good design for the national flag would be the present battle-flag as Union Jack, and the rest all white or all blue'... The final version of the second national flag, adopted May 1, 1863, did just this: it set the St. Andrew's Cross of stars in the Union Jack with the rest of the civilian banner entirely white."[26][27][28][29]

The Confederate Congress debated whether the white field should have a blue stripe and whether it should be bordered in red. William Miles delivered a speech supporting the simple white design that was eventually approved. He argued that the battle flag must be used, but it was necessary to emblazon it for a national flag, but as simply as possible, with a plain white field.[30] When Thompson received word the Congress had adopted the design with a blue stripe, he published an editorial on April 28 in opposition, writing that "the blue bar running up the center of the white field and joining with the right lower arm of the blue cross, is in bad taste, and utterly destructive of the symmetry and harmony of the design."[1][5] Confederate Congressman Peter W. Gray proposed the amendment that gave the flag its white field.[31] Gray stated that the white field represented "purity, truth, and freedom."[32]

Regardless of who truly originated the Stainless Banner's design, whether by heeding Thompson's editorials or Beauregard's letter, the Confederate Congress officially adopted the Stainless Banner on May 1, 1863. The flags that were actually produced by the Richmond Clothing Depot used the 1.5:1 ratio adopted for the Confederate navy's battle ensign, rather than the official 2:1 ratio.[11]

Initial reaction to the second national flag was favorable, but over time it became criticized for being "too white." Military officers also voiced complaints about the flag being too white, for various reasons, such as the danger of being mistaken for a flag of truce, especially on naval ships where it was too easily soiled.[13] The Columbia-based Daily South Carolinian observed that it was essentially a battle flag upon a flag of truce and might send a mixed message. Due to the flag's resemblance to one of truce, some Confederate soldiers cut off the flag's white portion, leaving only the canton.[33]

The first official use of the "Stainless Banner" was to drape the coffin of General Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson as it lay in state in the Virginia capitol, May 12, 1863.[34][35] As a result of this first usage, the flag received the alternate nickname of the "Jackson Flag".

Third flag: the "Blood-Stained Banner" (1865)

[edit]

|

|

|

| Third national flag (after March 4, 1865) | Third national flag as commonly manufactured, with a square canton | Third national flag variant produced from an example of the Second national flag |

Rogers lobbied successfully to have this alteration introduced in the Confederate Senate. Rogers defended his redesign as symbolizing the primary origins of the people of the Confederacy, with the saltire of the Scottish flag and the red bar from the flag of France, and having "as little as possible of the Yankee blue" — the Union Army wore blue, the Confederates gray.[13]

The Flag Act of 1865, passed by the Confederate congress near the very end of the War, describes the flag in the following language:

The Congress of the Confederate States of America do enact, That the flag of the Confederate States shall be as follows: The width two-thirds of its length, with the union (now used as the battle flag) to be in width three-fifths of the width of the flag, and so proportioned as to leave the length of the field on the side of the union twice the width of the field below it; to have the ground red and a broad blue saltire thereon, bordered with white and emblazoned with mullets or five pointed stars, corresponding in number to that of the Confederate States; the field to be white, except the outer half from the union to be a red bar extending the width of the flag.[12]

Due to the timing, very few of these third national flags were actually manufactured and put into use in the field, with many Confederates never seeing the flag. Moreover, the ones made by the Richmond Clothing Depot used the square canton of the second national flag rather than the slightly rectangular one that was specified by the law.[12]

State flags

[edit]Flag of Alabama (reverse)

(January 11, 1861)Flag of Florida

(September 13, 1861)Flag of Louisiana

(February 11, 1861)Flag of Mississippi

(March 30, 1861)Flag of North Carolina

(June 22, 1861)Flag of South Carolina

(January 26, 1861)Flag of Texas

(January 25, 1839)Flag of Virginia

(April 30, 1861)

Indian Territory

[edit]-

National Color of the 1st Cherokee Mounted Rifles[38]

Battle flag

[edit]

At the First Battle of Manassas, near Manassas, Virginia, the similarity between the "Stars and Bars" and the "Stars and Stripes" caused confusion and military problems. Regiments carried flags to help commanders observe and assess battles in the warfare of the era. At a distance, the two national flags were hard to tell apart.[39] Also, Confederate regiments carried many other flags, which added to the possibility of confusion.

After the battle, General P. G. T. Beauregard wrote that he was "resolved then to have [our flag] changed if possible, or to adopt for my command a 'Battle flag', which would be Entirely different from any State or Federal flag".[22] He turned to his aide, who happened to be William Porcher Miles, the former chairman of the Confederate Congress's Committee on the Flag and Seal. Miles described his rejected national flag design to Beauregard. Miles also told the Committee on the Flag and Seal about the general's complaints and request that the national flag be changed. The committee rejected the idea by a four-to-one vote, after which Beauregard proposed the idea of having two flags. He described the idea in a letter to his commanding General Joseph E. Johnston:

I wrote to [Miles] that we should have 'two' flags – a 'peace' or parade flag, and a 'war' flag to be used only on the field of battle – but congress having adjourned no action will be taken on the matter – How would it do us to address the War Dept. on the subject of Regimental or badge flags made of red with two blue bars crossing each other diagonally on which shall be introduced the stars, ... We would then on the field of battle know our friends from our Enemies.[22]

The flag that Miles had favored when he was chairman of the "Committee on the Flag and Seal" eventually became the battle flag and, ultimately, the Confederacy's most popular flag.

According to Museum of the Confederacy Director John Coski, Miles' design was inspired by one of the many "secessionist flags" flown at the South Carolina secession convention in Charleston of December 1860. That flag was a blue St George's Cross (an upright or Latin cross) on a red field, with 15 white stars on the cross, representing the slave-holding states,[40][41] and, on the red field, palmetto and crescent symbols. Miles received various feedback on this design, including a critique from Charles Moise, a self-described "Southerner of Jewish persuasion." Moise liked the design but asked that "... the symbol of a particular religion not be made the symbol of the nation." Taking this into account, Miles changed his flag, removing the palmetto and crescent, and substituting a heraldic saltire ("X") for the upright cross. The number of stars was changed several times as well. He described these changes and his reasons for making them in early 1861. The diagonal cross was preferable, he wrote, because "it avoided the religious objection about the cross (from the Jews and many Protestant sects), because it did not stand out so conspicuously as if the cross had been placed upright thus." He also argued that the diagonal cross was "more Heraldric [sic] than Ecclesiastical, it being the 'saltire' of Heraldry, and significant of strength and progress."[42]

According to Coski, the Saint Andrew's Cross (also used on the flag of Scotland as a white saltire on a blue field) had no special place in Southern iconography at the time. If Miles had not been eager to conciliate the Southern Jews, his flag would have used the traditional upright "Saint George's Cross" (as used on the flag of England, a red cross on a white field). James B. Walton submitted a battle flag design essentially identical to Miles' except with an upright Saint George's cross, but Beauregard chose the diagonal cross design.[43]

Miles' flag and all the flag designs up to that point were rectangular ("oblong") in shape. General Johnston suggested making it square to conserve material. Johnston also specified the various sizes to be used by different types of military units. Generals Beauregard and Johnston and Quartermaster General Cabell approved the 12-star Confederate Battle Flag's design at the Ratcliffe home, which served briefly as Beauregard's headquarters, near Fairfax Court House in September 1861. The 12th star represented Missouri. President Jefferson Davis arrived by train at Fairfax Station soon after and was shown the design for the new battle flag at the Ratcliffe House. Hetty Cary and her sister and cousin made prototypes. One such 12-star flag resides in the collection of Richmond's Museum of the Confederacy and the other is in the Confederate Memorial Hall Museum in New Orleans.

On November 28, 1861, Confederate soldiers in General Robert E. Lee's newly reorganized Army of Northern Virginia received the new battle flags in ceremonies at Centreville and Manassas, Virginia, and carried them throughout the Civil War. Beauregard gave a speech encouraging the soldiers to treat the new flag with honor and that it must never be surrendered. Many soldiers wrote home about the ceremony and the impression the flag had upon them, the "fighting colors" boosting morale after the confusion at the Battle of First Manassas. From then on, the battle flag grew in its identification with the Confederacy and the South in general.[44] The flag's stars represented the number of states in the Confederacy. The distance between the stars decreased as the number of states increased, reaching thirteen when the secessionist factions of Kentucky and Missouri joined in late 1861.[45]

The Army of Northern Virginia battle flag assumed a prominent place post-war when it was adopted as the copyrighted emblem of the United Confederate Veterans. Its continued use by the Southern Army's post-war veteran's groups, the United Confederate Veterans (U.C.V.) and the later Sons of Confederate Veterans, (S.C.V.), and elements of the design by related similar female descendants organizations of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, (U.D.C.), led to the assumption that it was, as it has been termed, "the soldier's flag" or "the Confederate battle flag."

The square "battle flag" is also properly known as "the flag of the Army of Northern Virginia". It was sometimes called "Beauregard's flag" or "the Virginia battle flag". A Virginia Department of Historic Resources marker declaring Fairfax, Virginia, as the birthplace of the Confederate battle flag was dedicated on April 12, 2008, near the intersection of Main and Oak Streets, in Fairfax, Virginia.[46][47][48]

To boost the morale of the Army of Tennessee, General Johnston introduced a new battle flag for the entire army. This flag bore a basic design similar to the one he had contributed to creating in Virginia in 1861 and had been commissioned in Mobile while he was in command in Mississippi in 1863. These flags for infantry and cavalry were to measure 37 by 54 inches. The white edging cross was about 2 inches wide and was often filled with battle honors. The stars were from 3 ½ inches to 4, and a 6 inch wide cross. Flags for artillery 30 by 41 inches overall.[1]

Naval flags

[edit]The fledgling Confederate States Navy adopted and used several types of flags, banners, and pennants aboard all CSN ships: jacks, battle ensigns, and small boat ensigns, as well as commissioning pennants, designating flags, and signal flags.[citation needed]

The first Confederate Navy jacks, in use from 1861 to 1863, consisted of a circle of seven to fifteen five-pointed white stars against a field of "medium blue." It was flown forward aboard all Confederate warships while they were anchored in port. One seven-star jack still exists today (found aboard the captured ironclad CSS Atlanta) that is actually "dark blue" in color (see illustration below, left).[49]

The second Confederate Navy Jack was a rectangular cousin of the Confederate Army's battle flag and was in use from 1863 until 1865. It existed in a variety of dimensions and sizes, despite the CSN's detailed naval regulations. The blue color of the diagonal saltire's "Southern Cross" was much lighter than the battle flag's dark blue.[49]

The second Navy Ensign of the ironclad CSS Atlanta

The 9-star first Naval ensign of the paddle steamer CSS Curlew

The 11-star ensign of the Confederate Privateer Jefferson Davis

A 12-star first Confederate Navy ensign of the gunboat CSS Ellis, 1861–1862

The Command flag of Captain William F. Lynch, flown as ensign of his flagship, CSS Seabird, 1862

Pennant of Admiral Franklin Buchanan, CSS Tennessee, at Battle of Mobile Bay, August 5, 1864

Admiral's Rank flag of Franklin Buchanan, flown from CSS Virginia during the first day of the Battle of Hampton Roads and also flown from the CSS Tennessee during the Battle of Mobile Bay

Confederate naval flag, captured when General William Sherman took Savannah, Georgia, 1864

The first national flag, also known as the Stars and Bars (see above), served from 1861 to 1863 as the Confederate Navy's first battle ensign. It was generally made with a 2:3 aspect ratio, but a few very wide 1:2 ratio ensigns still survive today in museums and private collections. As the Confederacy grew, so did the numbers of white stars on the ensign's dark blue canton: seven-, nine-, eleven-, and thirteen-star groupings were typical. Even a few fourteen- and fifteen-starred ensigns were made to include states expected to secede but never completely joined the Confederacy. [citation needed]

The second national flag was later adapted as a naval ensign, using a shorter 2:3 aspect ratio than the 1:2 ratio adopted by the Confederate Congress for the national flag. This particular battle ensign was the only example taken around the world, finally becoming the last Confederate flag lowered in the Civil War; this happened aboard the commerce raider CSS Shenandoah in Liverpool, England, on November 7, 1865.

National flag proposals

[edit]Hundreds of proposed national flag designs were submitted to the Confederate Congress during competitions to find a First National flag (February–May 1861) and Second National flag (April 1862; April 1863).

First National flag proposals

[edit]When the Confederate States of America was founded during the Montgomery Convention that took place on February 4, 1861, a national flag was not selected by the Convention due to not having any proposals. President Jefferson Davis' inauguration took place under the 1861 state flag of Alabama, and the celebratory parade was led by a unit carrying the 1861 state flag of Georgia.

Realizing that they quickly needed a national banner to represent their sovereignty, the Provisional Congress of the Confederate States set up the Committee on Flag and Seal. The chairman was William Porcher Miles, who was also the Representative of South Carolina in the Confederate House of Representatives.

The Committee began a competition to find a new national flag, with an unwritten deadline being that a national flag had to be adopted by March 4, 1861, the date of President Lincoln's inauguration. This would serve to show the world the South was truly sovereign. Hundreds of examples were submitted from across the Confederate States and from states that were not yet part of Confederacy (e.g. Kentucky), and even from Union states (such as New York). Many of the proposed designs paid homage to the Stars and Stripes, due to a nostalgia in early 1861 that many of the new Confederate citizens felt towards the Union. Some of the homages were outright mimicry, while others were less obviously inspired by the Stars and Stripes, yet were still intended to pay homage to that flag.

Those inspired by the Stars and Stripes were discounted almost immediately by the Committee due to mirroring the Union's flag too closely. While others were wildly different, many of which were very complex and extravagant, these were largely discounted due to the being too complicated and expensive to produce.

The winner of the competition was Nicola Marschall's "Stars and Bars" flag. The "Stars and Bars" flag was only selected by the Congress of March 4, 1861, the day of the deadline. The first flag was produced in rush, due to the date having already been selected to host an official flag-raising ceremony, W. P. Miles credited the speedy completion of the first "Stars and Bars" flag to "Fair and nimble fingers". This flag, made of Merino, was raised by Letitia Tyler over the Alabama state capitol. The Congress inspected two other finalist designs on March 4: One was a "Blue ring or circle on a field of red", while the other consisted of alternating red and blue stripes with a blue canton containing stars. These two designs were lost, and we only know of them thanks to an 1872 letter sent by William Porcher Miles to P. G. T. Beauregard.

William Porcher Miles, however, was not really happy with any of the proposals. He did not share in the nostalgia for the Union that many of his fellows Southerners felt, believing that the South's flag should be completely different from that of the North. To this end, he proposed his own flag design featuring a blue saltire on white Fimbriation with a field of red. (Miles had originally planned to use a blue St. George's Cross like that of the South Carolina Sovereignty Flag, but was dissuaded from doing so.) Within the blue saltire were seven white stars, representing the current seven states of the Confederacy, two on each of the left arms, one of each of the right arms, and one in the middle.

However, Miles' flag was not well received by the rest of the Congress. One Congressman even mocked it as looking "like a pair of Suspenders". Miles' flag lost out to the "Stars and Bars".

-

First variant of flag proposal by A. Bonand of Savannah, Georgia

-

Second variant of flag proposal by A. Bonand

-

Flag proposal submitted by the "Ladies of Charleston"

-

First variant of flag proposal by L. P. Honour of Charleston, South Carolina

-

L. P. Honour's second variant of First national flag proposal

-

Confederate First national flag proposal by John Sansom of Alabama

-

William Porcher Miles' flag proposal, ancestor flag of the Confederate Battle Flag

-

John G. Gaines' First national flag proposal

-

Flag proposal by J. M. Jennings of Lowndesboro, Alabama

-

Samuel White's flag proposal

-

Flag proposal submitted by an unknown person of Louisville, Kentucky

-

One of three finalist designs examined by Congress on March 4, 1861, lost out to Stars and Bars

-

Second of three finalists in the Confederate First national flag competition

-

Confederate flag proposal by E. G. Carpenter of Cassville, Georgia

-

Confederate flag proposal by Thomas H. Hobbs of Chattanooga, Tennessee

-

Flag proposal by Eugene Wythe Baylor of Louisiana

-

Flag proposal submitted by "H" of South Carolina

-

A Confederate flag proposal by Hamilton Coupes that was submitted on February 1, 1861

-

The Confederate national flag proposal of Irene Riddle of Eutaw, Alabama

-

This flag proposal was the first variant submitted by William T. Riddle of Eutaw, Alabama. Riddle submitted his flag proposals to Stephen Foster Hale on February 21, 1861.

-

Flag proposed in 1862

-

Flag proposed in 1863

-

Flag proposed in 1863

-

Congressman Swan's Amendment to Senate Bill №132

Flag variants

[edit]In addition to the Confederacy's national flags, a wide variety of flags and banners were flown by Southerners during the Civil War. Most famously, the "Bonnie Blue Flag" was used as an unofficial flag during the early months of 1861. It was flying above the Confederate batteries that first opened fire on Fort Sumter in Charleston harbor, in South Carolina beginning the Civil War. The "Van Dorn battle flag" was also carried by Confederate troops fighting in the Trans-Mississippi and Western theaters of war. Besides, many military units had their own regimental flags they would carry into battle.[50]

-

Flag of Knights of the Golden Circle

-

The "Bonnie Blue Flag"—an unofficial flag in 1861

-

The "Van Dorn battle flag" used in the Western theaters of operation

-

Flag of the Army of Northern Virginia or "Robert E. Lee Headquarters Flag"

-

7-star First national flag of the Confederate States Marine Corps

-

Flag of First Corps, Army of Tennessee

-

A Polk's Corps-style Battle Flag of the 10th Mississippi Infantry Regiment

-

The first battle flag of the Perote Guards (Company D, 1st Regiment Alabama Infantry). Flag officially used: September 1860 – Summer, 1861

-

George P. Gilliss flag, also known as the Biderman Flag, the one of the few Confederate flags captured in California (Sacramento)

-

The "Sibley Flag", Battle Flag of the Army of New Mexico, commanded by General Henry Hopkins Sibley.

-

The ensign of the Confederate States Revenue Service, designed by H. P. Capers of South Carolina on April 10, 1861.

-

Flag flown by Confederate Missouri regiments during the Vicksburg campaign.[51]

-

Flag variant with 12 stars that served as the Garrison Flag of Vicksburg, Mississippi during the Vicksburg campaign.

-

Flag of Fort Fisher.

-

Flag of the Cherokee Braves.

-

Flag of regiments of the Orphan Brigade.

-

Hardee battle flag.

-

6th Florida Hardee battle flag.

-

Cassidy battle flag.

-

Flag of the 1st Florida Infantry Regiment.

Controversy

[edit]

Though never having historically represented the Confederate States of America as a country, nor having been officially recognized as one of its national flags, the Battle Flag of the Army of Northern Virginia and its variants are now flag types commonly referred to as the Confederate Flag.

This design has become commonly regarded by opponents of its use as a symbol of racism and white supremacy or white nationalism, while supporters of it maintain that its modern use is as a symbol of regional cultural pride.[52][53]

It is also known as the rebel flag, Dixie flag, and Southern cross (not to be confused with another use of the term Southern Cross, referring to Crux, a constellation of the southern sky used on the coats of arms and flags of various countries and sub-national entities). It is sometimes incorrectly referred to as the Stars and Bars, the name of the first national Confederate flag.[54]

The "rebel flag" is considered by some to be a divisive and polarizing symbol in the United States.[55][56] A YouGov poll in 2020 of more than 34,000 Americans reported that 41% viewed the flag as representing racism, and 34% viewed it as symbolizing southern heritage.[57] A July 2021 Politico-Morning Consult poll of 1,996 registered voters reported that 47% viewed it as a symbol of Southern pride while 36% viewed it as a symbol of racism.[58][59]

Gallery

[edit]-

Drawing in the United Confederate Veterans 1895 Sponsor souvenir album

-

Jefferson Davis State Historic Site & Museum. The Bonnie Blue Flag is on the right.

-

Confederate National flag of Fort McAllister

-

Battle Flag of the Emmett Rifles

-

Confederate National Flag captured from Fort Jackson

-

Battle flag of the 11th Mississippi Infantry Regiment used at Antietam

-

Flag of the 1st Alabama Infantry Regiment

-

Flag of the 20th Texas Infantry Regiment

-

Flag of Terry’s Texas Rangers

-

Guidon of the company B, 2nd Florida Cavalry Regiment

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ William Tappan Thompson, editor of Savannah's Daily Morning News, used a different nickname for the flag, calling it "The White Man's Flag", saying that the flag's white field symbolized the "supremacy of the white man". But it was a nickname that never gained traction with the public.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10]

- ^ Although the officially specified proportions were 1:2, many of the flags that actually ended up being produced used a 1.5:1 aspect ratio.[11]

- ^ Although the officially designated design specified a rectangular canton, many of the flags that ended up being produced utilized a square-shaped canton.[12]

- ^ Catherine Stratton Ladd is said to have designed the first Confederate flag.[17][18]

- ^ Neither state voted to secede or ever came under full Confederate control. Nonetheless both were still represented in the Confederate Congress and had Confederate shadow governments composed of deposed former state politicians.

- ^ "Neither Arkansas nor Missouri enacted legislation to adopt an official State flag" (Cannon 2005, p. 48).

- ^ "A surviving Georgia flag in the collection of the Museum of the Confederacy in Richmond . . . places the arms on a red field" (Cannon 2005, p. 39).

- ^ "Despite . . . inaction of the Tennessee legislature, the flag recommended by Senator [Tazewell B.] Newman did see some limited use" (Cannon 2005, pp. 46-47).

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Preble 1872, pp. 414–417

- ^ Preble 1880, pp. 523–525

- ^ a b c Coski 2013. "A handful of contemporaries linked the new flag design to the "peculiar institution" that was at the heart of the South's economy, social system and polity: slavery. Bagby characterized the flag motif as the "Southern Cross" – the constellation, not a religious symbol – and hailed it for pointing 'the destiny of the Southern master and his African slave' southward to 'the banks of the Amazon,' a reference to the desire among many Southerners to expand Confederate territory into Latin America. In contrast, the Savannah, Ga., Morning News editor focused on the white field on which the Southern Cross was emblazoned. "As a people, we are fighting to maintain the heaven-ordained supremacy of the white man over the inferior or colored races. A White Flag would be thus emblematical of our cause." He dubbed the new flag "the White Man's Flag," a sobriquet that never gained traction."

- ^ a b Thompson, William T. (April 23, 1863). "Daily Morning News". Savannah, Georgia.[full citation needed]

- ^ a b c Thompson, William T. (April 28, 1863). "Daily Morning News". Savannah, Georgia.[full citation needed]

- ^ a b c Thompson, William T. (May 4, 1863). "Daily Morning News". Savannah, Georgia.[full citation needed]

- ^ a b Loewen, James W.; Sebesta, Edward H. (2010). The Confederate and Neo Confederate Reader: The Great Truth about the 'Lost Cause'. Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-60473-219-1. OCLC 746462600. Archived from the original on December 13, 2013. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

Confederates even showed their preoccupation with race in their flag. Civil War buffs know that 'the Confederate flag' waved today was never the Confederate States of America's official flag. Rather, it was the battle flag of the Army of Northern Virginia. During the war, the Confederacy adopted three official flags. The first, sometimes called 'the Stars and Bars,' drew many objections 'on account of its resemblance to that of the abolition despotism against which we are fighting,' in the words of the editor of the Savannah Morning News, quoted herein.

- ^ Kim, Kyle; Krishnakumar, Priya. "What you should know about the Confederate flag's evolution". Los Angeles Times. No. June 23, 2015. California. Archived from the original on July 12, 2015. Retrieved July 11, 2015.

- ^ Wood, Marie Stevens Walker (1957). Stevens-Davis and allied families: a memorial volume of history, biography, and genealogy. p. 44. Retrieved September 1, 2015.

This design was suggested by William T. Thompson, editor of the Savannah (Ga.) Morning News, who, in an editorial published April 23, 1863, stated that through this design could be attained all the...

- ^ a b Allen, Frederick (May 25, 1996). Atlanta Rising: The Invention of an International City 1946–1996. Taylor Trade. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-4616-6167-2. Retrieved September 1, 2015.

By modern standards, the greatest flaw of the 'Stainless Banner' was its other popular nickname, bestowed by William T. Thompson, editor of the Savannah Daily Morning News, who called it 'the White Man's Flag' and argued that it represented 'the cause of a superior race and a higher civilization contending against ignorance, infidelity, and barbarism' – a bit of racist rhetoric that is plainly unacceptable in current public discourse.

- ^ a b c "The Second Confederate National Flag (Flags of the Confederacy)". Archived from the original on February 9, 2009. Retrieved October 24, 2005.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b c "The Third Confederate National Flag (Flags of the Confederacy)". Archived from the original on January 30, 2009. Retrieved July 29, 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b c Coski 2005, pp. 17–18

- ^ "Southern Historical Society Papers, Volume 32., Confederate States' flags". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved January 7, 2024.

- ^ "Returned Flags Booklet, 1905 | A State Divided". PBS LearningMedia. Retrieved January 7, 2024.

- ^ "Nicola Marschall". The Encyclopedia of Alabama. April 25, 2011. Retrieved July 29, 2011.

The flag does resemble that of the Germanic European nation of Austria, which as a Prussian artist, Marschall would have known well.

- ^ "Ladd, Catherine". Appletons' Cyclopedia of American Biography, 1600-1889. Vol. 3. Appleton & Company. pp. 584–585.

- ^ "Ladd, Catherine". Encyclopedia of Virginia Biography. Vol. III. p. 196.

- ^ Hume, Edgar Erskine (August 1940). "Nicola Marschall: Excerpts from "The German Artist Who Designed the Confederate Flag and Uniform"". The American-German Review. Archived from the original on May 28, 2016. Retrieved June 26, 2015.

- ^ Commemorative Landscapes of North Carolina (March 19, 2010). "First Confederate Flag and Its Designer O.R. Smith, Louisburg". Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

- ^ Coski 2005, pp. 4–5

- ^ a b c Coski 2005, p. 8

- ^ "The Declarations of Causes of Seceding States". Civil War Trust. Retrieved February 23, 2016.

Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery—the greatest material interest of the world. Its labor supplies the product that constitutes the largest and most important portions of commerce of the earth. These products are peculiar to the climate verging on the tropical regions, and by an imperious law of nature, none but the black race can bear exposure to the tropical sun. These products have become necessities of the world, and a blow at slavery is a blow at commerce and civilization. That blow has been long aimed at the institution and was at the point of reaching its consummation. No choice left us but submission to abolition's mandates, or a dissolution of the Union, whose principles had been subverted to work out our ruin. That we do not overstate the dangers to our institution, a reference to a few facts will sufficiently prove.

- ^ Ben Brumfield (June 24, 2015). "Confederate battle flag: Separating the myths from facts". CNN.

- ^ "Confederate Flag History". www.civilwar.com. Retrieved March 4, 2023.

- ^ Bonner, Robert E., "Flag Culture and the Consolidation of Confederate Nationalism." Journal of Southern History, Vol. 68, No. 2 (May 2002), 318–319.

- ^ Coski 2013. "Some congressmen and newspaper editors favored making the Army of Northern Virginia battle flag (in a rectangular shape) itself the new national flag. But Beauregard and others felt the nation needed its own distinctive symbol, and so recommended that the Southern Cross be emblazoned in the corner of a white field."

- ^ "Letter of Beauregard to Villere, April 24, 1863". Daily Dispatch. Richmond, VA. May 13, 1863.

- ^ Martinez, J. Michael; Richardson, William D.; McNinch-Su, Ron (2000). Confederate Symbols in the Contemporary South. University Press of Florida. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-8130-1758-7.

- ^ Coski 2005, pp. 16–17

- ^ Journal of the Confederate Congress, Volume 6, p.477

- ^ Richmond Whig, May 5, 1863

- ^ Coski 2005, p. 18

- ^ John D. Wright, The Language of the Civil War, p.284

- ^ Coski 2005, p. 17

- ^ "Don Healy's Native American Flags: Choctaw Nation." Retrieved January 15, 2014.

- ^ Healy, Donald T.; Orenski, Peter J. (2003). Native American flags. Norman. p. 211. ISBN 978-0-8061-5575-3. OCLC 934794160.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Cannon 2005, p. 64.

- ^ Gevinson, Alan. "The Reason Behind the 'Stars and Bars". Teachinghistory.org. Retrieved October 8, 2011.

- ^ Coski 2009, p. 5

- ^ Coski 2005, p. 5

- ^ Coski 2005, p. 5: "describes the 15 stars and the debate on religious symbolism."

- ^ Coski 2005, pp. 6–8

- ^ Coski 2005, p. 10

- ^ Coski 2005, p. 11

- ^ "Birthplace of the Confederate Battle Flag". The Historical Marker Database.

- ^ 37 New Historical Markers for Virginia's Roadways (PDF) (Report). Notes on Virginia. Virginia Department of Historic Resources. 2008. p. 71.

B-261: Birthplace of the Confederate Battle Flag

- ^ "2008 Virginia Marker Dedication: Birthplace of the Confederate Battle Flag". FairfaxRifles.org. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- ^ a b Loeser, Pete. "American Civil War Flags". Historical Flags of Our Ancestors. Retrieved July 22, 2019.

- ^ North & South – The Official Magazine of the Civil War Society, Volume 11, Number 2, Page 30, Retrieved April 16, 2010, "The Stars and Bars" Archived July 14, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Tucker 1993, p. 122.

- ^ Chapman, Roger (2011). Culture Wars: An Encyclopedia of Issues, Viewpoints, and Voices. M.E. Sharpe. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-7656-2250-1. Retrieved February 21, 2013.

- ^ McWhorter, Diane (April 3, 2005). "'The Confederate Battle Flag': Clashing Symbols". The New York Times. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- ^ Coski 2005, pp. 58

- ^ Little, Becky (June 26, 2015). "Why the Confederate Flag Made a 20th Century Comeback". National Geographic. Archived from the original on August 15, 2019. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ The Associated Press (July 10, 2015). "Confederate flag removed: A history of the divisive symbol". Oregon Live.

- ^ Sanders, Linley (January 13, 2020). "What the Confederate flag means in America today". yougov.com. Retrieved October 28, 2020.

For a plurality of Americans, the Confederate flag represents racism (41%). But for about one-third of Americans (34%) – particularly adults over 65, those living in rural communities, or non-college-educated white Americans – the flag symbolizes heritage.

- ^ "American Electorate Continues to Favor Leaving Confederate Relics in Place". July 14, 2021.

- ^ Morning Consult; Politico. "National Tracking Poll #2107045 / July 09-12, 2021 / Crosstabulation Results" (PDF). p. 176.

Sources

[edit]- Bonner, Robert (2002). Colors and Blood: Flag Passions of the Confederate South. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-11949-X.

- Cannon, Devereaux D. Jr. (2005) [1st pub. St. Luke's Press:1988]. The Flags of the Confederacy: An Illustrated History. Gretna: Pelican Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-565-54109-2.

- Coski, John M. (2005). The Confederate Battle Flag: America's Most Embattled Emblem. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01722-1.

- Coski, John M. (2009). The Confederate Battle Flag. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02986-6. Retrieved November 24, 2016.

- Coski, John M. (May 13, 2013). "The Birth of the 'Stainless Banner'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 7, 2019. Retrieved January 27, 2014.

- Katcher, Phillip; Scollins, Rick (1993). Flags of the American Civil War 1: Confederate. Osprey Men-At-War Series. Osprey Publishing Company. ISBN 1-85532-270-6.

- Madaus, H. Michael. Rebel Flags Afloat: A Survey of the Surviving Flags of the Confederate States Navy, Revenue Service, and Merchant Marine. Flag Research Center, 1986, Winchester, MA. ISSN 0015-3370. (Eighty-page, all Confederate naval flags issue of "The Flag Bulletin," magazine #115.)

- Marcovitz, Hal. The Confederate Flag, American Symbols and Their Meanings. Mason Crest Publishers, 2002. ISBN 1-59084-035-6.

- Martinez, James Michael; Richardson, William Donald; McNinch-Su, Ron (2000). Confederate Symbols in the Contemporary South. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida. pp. 284–285. ISBN 0-8130-1758-0.

- Preble, George Henry (1872). Our Flag: Origin and Progress of the Flag of the United States of America, with an Introductory Account of the Symbols, Standards, Banners and Flags of Ancient and Modern Nations. Albany: Joel Munsell. p. 414. OCLC 612597989.

as a people we are fighting to.

- Preble, George Henry (1880). History of the Flag of the United States of America: And of the Naval and Yacht-Club Signals, Seals, and Arms, and Principal National Songs of the United States, with a Chronicle of the Symbols, Standards, Banners, and Flags of Ancient and Modern Nations (2nd revised ed.). Boston: A. Williams and Company. p. 523. OCLC 645323981.

William Ross Postell Flag.

- Silkenat, David. Raising the White Flag: How Surrender Defined the American Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019. ISBN 978-1-4696-4972-6.

- Tucker, Phillip Thomas (1993). The South's Finest: The First Missouri Confederate Brigade From Pea Ridge to Vicksburg. Shippensburg, Pennsylvania: White Mane Publishing Co. ISBN 0-942597-31-1.

"Southern Confederacy" (Atlanta, Georgia), 5 Feb 1865, pg 2. Congressional, Richmond, 4 Feb: A bill to establish the flag of the Confederate States was adopted without opposition, and the flag was displayed in the Capitol today. The only change was a substitution of a red bar for one-half of the white field of the former flag, composing the flag's outer end.

![Flag of the Choctaw Nation (c. 1860)[36]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/2c/Flag_of_the_Choctaw_Brigade.svg/167px-Flag_of_the_Choctaw_Brigade.svg.png)

![Flag of the Creek Nation (c. 1861)[citation needed]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/33/Flag_of_the_Confederate_States_for_the_Muscogee_%28Creek%29_Nation.svg/150px-Flag_of_the_Confederate_States_for_the_Muscogee_%28Creek%29_Nation.svg.png)

![Flag of the Seminole Nation (c. 1861)[37]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5e/Seminola_confederats.svg/180px-Seminola_confederats.svg.png)

![National Color of the 1st Cherokee Mounted Rifles[38]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/99/Flag_of_the_Cherokee_Braves.svg/180px-Flag_of_the_Cherokee_Braves.svg.png)

![Flag flown by Confederate Missouri regiments during the Vicksburg campaign.[51]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/36/Missouri_Regiments_Army_Banner.svg/167px-Missouri_Regiments_Army_Banner.svg.png)