Airbus A350

| Airbus A350 | |

|---|---|

Qatar Airways was the A350-900 launch operator on 15 January 2015. | |

| General information | |

| Role | Wide-body airliner |

| National origin | Multi-national[a] |

| Manufacturer | Airbus |

| Status | In service |

| Primary users | Singapore Airlines |

| Number built | 628 as of November 2024[update][1] |

| History | |

| Manufactured | 2010–present[2] |

| Introduction date | 15 January 2015, with Qatar Airways[3] |

| First flight | 14 June 2013[4] |

The Airbus A350 is a long-range, wide-body twin-engine airliner developed and produced by Airbus. The initial A350 design proposed in 2004, in response to the Boeing 787 Dreamliner, would have been a development of the Airbus A330 with composite wings and new engines. Due to inadequate market support, Airbus switched in 2006 to a clean-sheet "XWB" (eXtra Wide Body) design, powered by two Rolls-Royce Trent XWB high bypass turbofan engines. The prototype first flew on 14 June 2013 from Toulouse, France. Type certification from the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) was obtained in September 2014, followed by certification from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) two months later.

The A350 is the first Airbus aircraft largely made of carbon-fibre-reinforced polymers. The fuselage is designed around a nine-abreast economy cross-section, an increase from the eight-abreast A330/A340. It has a common type rating with the A330. The airliner has two variants: the A350-900 typically carries 300 to 350 passengers over a 15,000 kilometre (8,100 nmi; 9,300 mi) range, and has a 283 tonne (617,300 lb) maximum takeoff weight (MTOW); the longer A350-1000 accommodates 350 to 410 passengers and has a maximum range of 16,500 km (8,900 nmi; 10,300 mi) and a 322 tonne (710,000 lb) MTOW.

On 15 January 2015, the first A350-900 entered service with Qatar Airways, followed by the A350-1000 on 24 February 2018 with the same launch operator. As of November 2024[update], Singapore Airlines is the largest operator with 65 aircraft in its fleet, while Turkish Airlines is the largest customer with 110 aircraft on order. A total of 1,345 A350 family aircraft have been ordered and 628 delivered, of which 627 aircraft are in service with 38 operators. The global A350 fleet has completed more than 1.58 million flights on more than 1,240 routes, transporting more than 400 million passengers with one hull loss being an airport-safety–related accident. It succeeds the A340 and competes against Boeing's large long-haul twinjets, the Boeing 777, its future successor, the 777X, and the 787.

Development

[edit]Background and early designs

[edit]Airbus initially rejected Boeing's claim that the Boeing 787 Dreamliner would be a serious threat to the Airbus A330, stating that the 787 was just a reaction to the A330 and that no response was needed. When airlines urged Airbus to provide a competitor, Airbus initially proposed the "A330-200Lite", a derivative of the A330 featuring improved aerodynamics and engines similar to those on the 787. The company planned to announce this version at the 2004 Farnborough Airshow, but did not proceed.[5]

On 16 September 2004, Airbus president and chief executive officer Noël Forgeard confirmed the consideration of a new project during a private meeting with prospective customers. Forgeard did not give a project name, and did not state whether it would be an entirely new design or a modification of an existing product. Airline dissatisfaction with this proposal motivated Airbus to commit €4 billion to a new airliner design.[5]

On 10 December 2004, Airbus' shareholders, EADS and BAE Systems, approved the "authorisation to offer" for the A350, expecting a 2010 service entry. Airbus then expected to win more than half of the 250-300-seat aircraft market, estimated at 3,100 aircraft overall over 20 years. Based on the A330, the 245-seat A350-800 was to fly over a 8,600 nmi (15,900 km; 9,900 mi) range and the 285-seat A350-900 over a 13,900 km (7,500 nmi; 8,600 mi) range. Fuel efficiency would improve by over 10% with a mostly carbon fibre reinforced polymer wing and initial General Electric GEnx-72A1 engines, before offering a choice of powerplant.[6] It had a common fuselage cross-section with the A330 and also a new horizontal stabiliser.[5]

On 13 June 2005 at the Paris Air Show, Middle Eastern carrier Qatar Airways announced that they had placed an order for 60 A350s. In September 2006 the airline signed a memorandum of understanding with General Electric (GE) to launch the GEnx-1A-72 engine for the new airliner model.[7][8][9] Emirates sought a more improved design and decided against ordering the initial version of the A350.[10][11]

On 6 October 2005, the programme's industrial launch was announced with an estimated development cost of around €3.5 billion.[5] The A350 was initially planned to be a 250 to 300-seat twin-engine wide-body aircraft derived from the existing A330's design. Under this plan, the A350 would have modified wings and new engines while sharing the A330's fuselage cross-section. For this design, the fuselage was to consist primarily of aluminium-lithium rather than the carbon-fibre-reinforced polymer (CFRP) fuselage on the Boeing 787. The A350 would see entry in two versions: the A350-800 with a 8,800 nmi (16,300 km; 10,100 mi) range with a typical passenger capacity of 253 in a three-class configuration, and the A350-900 with 7,500 nmi (13,900 km; 8,600 mi) range and a 300-seat three-class configuration. The A350 was designed to be a direct competitor to the Boeing 787-9 and 777-200ER.[5]

The original A350 design was publicly criticised by two of Airbus's largest customers, International Lease Finance Corporation (ILFC) and GE Capital Aviation Services (GECAS). On 28 March 2006, ILFC President Steven F. Udvar-Házy urged Airbus to pursue a clean-sheet design or risk losing market share to Boeing and branded Airbus's strategy as "a Band-aid reaction to the 787", a sentiment echoed by GECAS president Henry Hubschman.[12][13] In April 2006, while reviewing bids for the Boeing 787 and A350, the CEO of Singapore Airlines (SIA) Chew Choon Seng, commented that "having gone through the trouble of designing a new wing, tail, and cockpit, [Airbus] should have gone the whole hog and designed a new fuselage."[14]

Airbus responded that they were considering A350 improvements to satisfy customer demands. Airbus's then-CEO Gustav Humbert stated, "Our strategy isn't driven by the needs of the next one or two campaigns, but rather by a long-term view of the market and our ability to deliver on our promises."[15][16] As major airlines such as Qantas and Singapore Airlines selected the 787 over the A350, Humbert tasked an engineering team to produce new alternative designs.[17][18] One such proposal, known internally as "1d", formed the basis of the A350 redesign.[18]

Redesign and launch

[edit]

On 14 July 2006, during the Farnborough International Airshow, the redesigned aircraft was designated "A350 XWB" (Xtra-Wide-Body).[19] Within four days, Singapore Airlines agreed to order 20 A350 XWBs with options for another 20 A350 XWBs.[20]

The proposed A350 was a new design, including a wider fuselage cross-section, allowing seating arrangements ranging from an eight-abreast low-density premium economy layout to a ten-abreast high-density seating configuration for a maximum seating capacity of 440–475 depending on variant.[21][22] The A330 and previous iterations of the A350 would only be able to accommodate a maximum of eight seats per row. The 787 is typically configured for nine seats per row.[23] The 777 accommodates nine or ten seats per row, with more than half of recent 777s being configured in a ten-abreast layout that will come standard on the 777X.[24] The A350 cabin is 12.7 cm (5.0 in) wider at the eye level of a seated passenger than the 787's cabin,[25] and 28 cm (11 in) narrower than the Boeing 777's cabin (see the Wide-body aircraft comparison of cabin widths and seating). All A350 passenger models have a range of at least 8,000 nmi (14,816 km; 9,206 mi). The redesigned composite fuselage allows for higher cabin pressure and humidity, and lower maintenance costs.

On 1 December 2006, the Airbus board of directors approved the industrial launch of the A350-800, -900, and -1000 variants.[26] The delayed launch decision was a result of delays to the Airbus A380[27] and discussions on how to fund development. EADS CEO Thomas Enders stated that the A350 programme was not a certainty, citing EADS/Airbus's stretched resources.[28] However, it was decided programme costs are to be borne mainly from cash-flow. First delivery for the A350-900 was scheduled for mid-2013, with the -800 and -1000 following on 12 and 24 months later, respectively.[26] New technical details of the A350 XWB were revealed at a press conference in December 2006. Chief operating officer, John Leahy indicated existing A350 contracts were being re-negotiated due to price increases compared to the original A350s contracted. On 4 January 2007, Pegasus Aviation Finance Company placed the first firm order for the A350 XWB with an order for two aircraft.[29]

The design change imposed a two-year delay into the original timetable and increased development costs from US$5.5 billion (€5.3 billion) to approximately US$10 billion (€9.7 billion).[30] Reuters estimated the A350's total development cost at US$15 billion (€12 billion or £10 billion).[31][32] The original mid-2013 delivery date of the A350 was changed, as a longer than anticipated development forced Airbus to delay the final assembly and first flight of the aircraft to the third quarter of 2012 and second quarter of 2013 respectively. As a result, the flight test schedule was compressed from the original 15 months to 12 months. A350 programme chief Didier Evrard stressed that delays only affected the A350-900 while the -800 and -1000 schedules remained unchanged.[33] Airbus' 2019 earnings report indicated the A350 programme had broken even that year.[citation needed]

Design phase

[edit]

Airbus suggested Boeing's use of composite materials for the 787 fuselage was premature, and that the new A350 XWB was to feature carbon fibre panels only for the main fuselage skin. However, after facing criticism for maintenance costs,[34] Airbus confirmed in early September 2007 that it would also use carbon fibre for fuselage frames.[35][36] The composite frames would feature aluminium strips to ensure the electrical continuity of the fuselage, for dissipating lightning strikes.[37] Airbus used a full mock up fuselage to develop the wiring, a different approach from the A380, on which the wiring was all done on computers.[38]

In 2006, Airbus confirmed development of a full bleed air system on the A350, as opposed to the 787's bleedless configuration.[39][40][41] Rolls-Royce agreed with Airbus to supply a new variant of the Trent turbofan engine for the A350 XWB, named Trent XWB. In 2010, after low-speed wind tunnel tests, Airbus finalised the static thrust at sea level for all three proposed variants to the 74,000–94,000 lbf (330–420 kN) range.[42]

GE stated it would not offer the GP7000 engine on the aircraft, and that previous contracts for the GEnx on the original A350 did not apply to the XWB.[43] Engine Alliance partner Pratt & Whitney seemed to be unaligned with GE on this, having publicly stated that it was looking at an advanced derivative of the GP7000.[44] In April 2007, former Airbus CEO Louis Gallois held direct talks with GE management over developing a GEnx variant for the A350 XWB.[45][46] In June 2007, John Leahy indicated that the A350 XWB would not feature the GEnx engine, saying that Airbus wanted GE to offer a more efficient version for the airliner.[47] Since then, the largest GE engines operators, which include Emirates, US Airways, Hawaiian Airlines and ILFC have selected the Trent XWB for their A350 orders. In May 2009, GE said that if it were to reach a deal with Airbus to offer the current 787-optimised GEnx for the A350, it would only power the -800 and -900 variants. GE believed it could offer a product that outperforms the Trent 1000 and Trent XWB, but was reluctant to support an aircraft competing directly with its GE90-115B-powered 777 variants.[48]

In January 2008, French-based Thales Group won a US$2.9 billion (€2 billion) 20-year contract to supply avionics and navigation equipment for the A350 XWB, beating Honeywell and Rockwell Collins.[49] US-based Rockwell Collins and Moog Inc. were chosen to supply the horizontal stabiliser actuator and primary flight control actuation, respectively. The flight management system incorporated several new safety features.[50] Regarding cabin ergonomics and entertainment, in 2006 Airbus signed a firm contract with BMW for development of an interior concept for the original A350.[51] On 4 February 2010, Airbus signed a contract with Panasonic Avionics Corporation to deliver in-flight entertainment and communication (IFEC) systems for the Airbus A350 XWB.[52]

Production

[edit]

In 2008, Airbus planned to start cabin furnishing early in parallel with final assembly to cut production time in half.[53] The A350 XWB production programme sees extensive international collaboration and investments in new facilities: Airbus constructed 10 new factories in Western Europe and the US, with extensions carried out on three further sites.[54]

Among the new buildings was a £570 million (US$760 million or €745 million) composite facility in Broughton, Wales, which would be responsible for the wings.[55] In June 2009, the National Assembly for Wales announced provision of a £28 million grant to provide a training centre, production jobs and money toward the new production centre.[56]

Airbus manufactured the first structural component in December 2009.[57] Production of the first fuselage barrel began in late 2010 at its production plant in Illescas, Spain.[58] Construction of the first A350-900 centre wingbox was set to start in August 2010.[59] The new composite rudder plant in China opened in early 2011.[60] The forward fuselage of the first A350 was delivered to the final assembly plant in Toulouse on 29 December 2011.[61] Final assembly of the first A350 static test model was started on 5 April 2012.[62] Final assembly of the first prototype A350 was completed in December 2012.[63]

In 2018, the unit cost of the A350-900 was US$317.4 million and the A350-1000 was US$366.5 million.[64] The production rate was expected to rise from three aircraft per month in early 2015 to five at the end of 2015, and would ramp to ten aircraft per month by 2018.[65] In 2015, 17 planes would be delivered and the initial dispatch reliability was 98%.[66] Airbus announced plans to increase its production rate from 10 monthly in 2018 to 13 monthly from 2019 and six A330 are produced monthly.[67]

Around 90 deliveries were expected for 2018, with 15% or ≈14 units being A350-1000 variants.[68] That year, 93 aircraft were delivered, three more than expected.[69] In 2019, Airbus delivered 112 A350s (87 A350-900s and 25 A350-1000s) at a rate of 10 per month, and were going to keep the rate around nine to 10 per month, to reflect softer demand for widebodies, as the backlog reached 579 − or 5.2 years of production at a constant rate.[70]

The COVID-19 pandemic caused the decrease of A350 production from 9.5 per month to six per month, since April 2020.[71] After the pandemic a ramp-up is planned, aiming to reach a rate of 9 per month by the end of 2025.[72] As the pre-pandemic rate of 10 monthly is aimed for by 2026, by April 2024 Airbus was planning a 12-monthly production rate by 2028 after securing 281 net orders in 2023.[73]

Testing and certification

[edit]

The first Trent engine test was made on 14 June 2010.[74] The Trent XWB's flight test programme began use on the A380 development aircraft in early 2011, ahead of engine certification in late 2011. On 2 June 2013, the Trent XWB engines were powered up on the A350 for the first time. Airbus confirmed that the flight test programme would last 12 months and use five test aircraft.[75]

The A350's maiden flight took place on 14 June 2013 from the Toulouse–Blagnac Airport.[4] Airbus's chief test pilot said, "it just seemed really happy in the air...all the things we were testing had no major issues at all."[76] It flew for four hours, reaching Mach 0.8 at 25,000 feet after retracting the landing gear and starting a 2,500 h flight test campaign.[77] Costs for developing the aircraft were estimated at €11 billion (US$15 billion or £9.5 billion) in June 2013.[78]

A350 XWB msn. 2 underwent two and a half weeks of climatic tests in the unique McKinley Climatic Laboratory at Eglin Air Force Base, Florida, in May 2014, and was subjected to multiple climatic and humidity settings from 45 °C (113 °F) to −40 °C (−40 °F).[79]

The A350 received type certification from the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) on 30 September 2014.[80] On 15 October 2014, EASA approved the A350-900 for ETOPS (Extended-range Twin-engine Operations Performance Standards) 370, allowing it to fly more than six hours on one engine and making it the first airliner to be approved for "ETOPS Beyond 180 minutes" before entry into service.[81] Later that month Airbus received regulatory approval for a Common Type Rating for pilot training between the A350 XWB and A330.[82] On 12 November 2014, the A350 received certification from the FAA.[83] On 1 August 2017, the EASA issued an airworthiness directive mandating operators to power cycle (reset) early A350-900s before 149 hours of continuous power-on time, reissued in July 2019.[84]

Entry into service

[edit]

In June 2011, the A350-900 was scheduled to enter service in the first half of 2014, with the -800 to enter service in mid-2016, and the -1000 in 2017.[85] In July 2012, Airbus delayed the -900's introduction by three months to the second half of 2014.[86] The delivery to launch customer Qatar Airways took place on 22 December 2014.[87] The first commercial flight was made on 15 January 2015 between Doha and Frankfurt.[3]

The first A350-1000 was assembled in 2016 and had its first flight on 24 November 2016.[88] The aircraft was then delivered on 20 February 2018 to Qatar Airways, which had also been the launch operator of the -900.[89] and entered the commercial service with a flight from Doha to London on 24 February 2018.[90]

Shorter A350-800

[edit]The 60.45 m (198.3 ft)-long A350-800 was designed to seat 276 passengers in a typical three-class configuration with a range of 8,245 nmi (15,270 km; 9,488 mi) with an MTOW of 259 t (571,000 lb).[91]

In January 2010, Airbus opted to develop the -800 as a shrink of the baseline -900 to simplify development and increase its payload by 3 t (6,600 lb) or its range by 250 nmi (460 km; 290 mi), but this led to a fuel burn penalty of "a couple of percent", according to John Leahy.[92] The previously planned optimisation to the structure and landing gear was not beneficial enough against better commonality and maximum takeoff weight increase by 11t from 248t.[93] The −800's fuselage is 10 frames shorter (six forward and four aft of wing) than the −900 aircraft.[94] It was designed to supplement the Airbus A330-200 long-range twin.[95] Airbus planned to decrease structural weight in the -800 as development continued, which should have been around airframe 20.[96]

While its backlog reached 182 in mid-2008, it diminished since 2010 as customers switched to the larger -900.[97] After launching the Airbus A330neo at the 2014 Farnborough Airshow, Airbus dropped the A350-800, with its CEO Fabrice Brégier saying "I believe all of our customers will either convert to the A350-900 or the A330neo".[98] He later confirmed at a September 2014 press conference that development of the A350-800 had been "cancelled".[99] There were 16 orders left for the -800 since Yemenia switched to the -900 and Hawaiian Airlines moved to the A330neo in December 2014: eight for Aeroflot and eight for Asiana Airlines, both also having orders for the -900.[100] In January 2017, Aeroflot and Airbus announced the cancellation of its -800 order, leaving Asiana Airlines as the only customer for the variant.[101] After the negotiation between Airbus and Asiana Airlines,[102] Asiana converted orders of eight A350-800s and one A350-1000 to nine A350-900s.[103]

Longer A350-1000

[edit]In 2011, Airbus redesigned the A350-1000 with higher weights and a more powerful engine variant to provide more range for trans-Pacific operations. This boosted its appeal to Cathay Pacific and Singapore Airlines, who were committed to purchase 20 Boeing 777-9s, and to United Airlines, which was considering Boeing 777-300ERs to replace its 747-400s.[104] Emirates was disappointed with the changes and cancelled its order for 50 A350-900s and 20 A350-1000s, instead of changing the whole order to the larger variant.[104]

Assembly of the first fuselage major components started in September 2015.[105] In February 2016, final assembly started at the A350 Final Assembly Line in Toulouse. Three flight test aircraft were planned, with entry into service scheduled for mid-2017.[106] The first aircraft completed its body join on 15 April 2016.[107] Its maiden flight took place on 24 November 2016.[88]

The A350-1000 flight test programme planned for 1,600 flight hours; 600 hours on the first aircraft, MSN59, for the flight envelope, systems and powerplant checks; 500 hours on MSN71 for cold and warm campaigns, landing gear checks and high-altitude tests; and 500 hours on MSN65 for route proving and ETOPS assessment, with an interior layout for cabin development and certification.[108] In cruise at Mach 0.854 (911.9 km/h; 492.4 kn) and 35,000 ft, its fuel flow at 259 t (571,000 lb) is 6.8 t (15,000 lb) per hour within a 5,400 nautical miles (10,000 km; 6,200 mi), 11+1⁄2 hours early long test flight.[109] Flight tests allowed raising the MTOW from 308 to 316 t (679,000 to 697,000 lb), the 8 t (18,000 lb) increase giving 450 nmi (830 km; 520 mi) more range.[110] Airbus then completed functional and reliability testing.[111]

Type Certification was awarded by EASA on 21 November 2017,[112] along FAA certification. The first serial unit was on the final assembly line in early December.[113] After its maiden flight on 7 December 2017, delivery to launch customer Qatar Airways slipped to early 2018.[114] The delay was due to issues with the business class seat installation.[115] It was delivered on 20 February 2018[116] and entered commercial service on Qatar Airways' Doha to London Heathrow route on 24 February 2018.[117]

Possible further stretch

[edit]Airbus has explored the possibility of a further stretch offering 45 more seats.[118] A potential 4 m (13 ft) stretch would remain within the exit limit of four door pairs, and a modest MTOW increase from 308 t to 319 t would need only 3% more thrust, within the Rolls-Royce Trent XWB-97 capabilities, and would allow a 7,600 nmi (14,100 km; 8,700 mi) range to compete with the 777-9's capabilities.[119] This variant was to be a replacement for the 747-400,[120] tentatively called the A350-8000,[121] -2000[122] or -1100.[118]

At the June 2016 Airbus Innovation Days, chief commercial officer John Leahy was concerned about the size of a 400-seat market besides the Boeing 747-8 and the 777-9 and chief executive Fabrice Brégier feared such an aircraft could cannibalise demand for the -1000.[122] The potential 79 m-long (258 ft) aeroplane was competing against a hypothetical 777-10X for Singapore Airlines.[123] At the 2017 Paris Air Show, the concept was shelved for lacking market appeal and in January 2018 Brégier focused on enhancing the A350-900/1000 to capture potential before 2022/2023, when it would be possible to stretch the A350 with a new engine generation.[124]

Improvements

[edit]In October 2017, Airbus was testing extended sharklets, which could offer 100–140 nmi (185–259 km; 115–161 mi) extra range and reduce fuel burn by 1.4–1.6%.[125] The wing twist is being changed for the wider, optimised spanload pressure distribution, and will be used for the Singapore Airlines A350-900ULR in 2018 before spreading to other variants.[126] On 26 June 2018, Iberia was the first to receive the upgraded -900, with a 280 t (620,000 lb) MTOW version for an 8,200 nmi (15,200 km; 9,400 mi) range with 325 passengers in three classes.[127][128]

By April 2019, Airbus was testing a hybrid laminar flow control (HLFC) on the leading edge of an A350 prototype vertical stabiliser, with passive suction similar to the boundary layer control on the Boeing 787-9 tail, but unlike the natural laminar flow BLADE, within the same EU Clean Sky programme.[129]

On 30 September 2022, a 1.2 t (2,600 lb) weight reduction and a 3 t (6,600 lb) MTOW increase was announced, along with a wider interior cabin to offer 30 additional seats.[130] The interior changes include moving the cockpit wall forward, moving the aft pressure bulkhead one frame further aft and resculpting the sidewalls to allow ten-abreast 17-inch seats.[131]

New Engine Option

[edit]By November 2018, Airbus was hiring in Toulouse and Madrid to develop a re-engined A350neo. Although its launch is not guaranteed, it would be delivered in the mid-2020s, after the A321XLR and a stretched A320neo "plus", potentially competing with the Boeing New Midsize Airplane. Service entry would be determined by ultra-high bypass ratio engine developments pursued by Pratt & Whitney, testing its Geared Turbofan upgrade; Safran Aircraft Engines, ground testing a demonstrator from 2021; and Rolls-Royce, targeting a 2025 Ultrafan service entry. The production target is a monthly rate of 20 A350neos, up from 10.[132]

In November 2019, General Electric was offering an advanced GEnx-1 variant with a bleed air system and improvements from the GE9X, developed for the delayed Boeing 777X, to power a proposed A350neo from the mid-2020s.[133] In 2021, Rolls Royce signed an exclusive deal to supply A350-900 engines until 2030, following previous similar commitments for the A350-1000.[134]

Design

[edit]

Airbus expected 10% lower airframe maintenance compared with the original A350 design and 14% lower empty seat weight than the Boeing 777.[135] Design freeze for the A350-900 was achieved in December 2008.[136] The airframe is made out of 53% composites: CFRP for the empennage (vertical and horizontal tailplanes), the wing (centre and outer box; including covers, stringers, and spars), and fuselage (keel beam, rear fuselage, skin, and frame); 19% aluminium and aluminium–lithium alloy for ribs, floor beams, and gear bays; 14% titanium for landing gears, pylons, and attachments; 6% steel; and 8% miscellaneous.[137] The A350's competitor, the Boeing 787, is 50% composites, 20% aluminium, 15% titanium, 10% steel, and 5% other.[138]

Fuselage

[edit]

The A350 features a new composite fuselage with a constant width from door 1 to door 4, unlike previous Airbus aircraft, to provide maximum usable volume.[139] The double-lobe (ovoid) fuselage cross-section has a maximum outer diameter of 5.97 m (19.6 ft), compared to 5.64 m (18.5 ft) for the A330/A340.[140] The cabin's internal width is 5.61 m (18.4 ft) at armrest level compared to 5.49 m (18.0 ft) in the Boeing 787[141] and 5.87 m (19.3 ft) in the Boeing 777. It allows for an eight-abreast 2–4–2 arrangement in a premium economy layout,[b] with the seats being 49.5 cm (19.5 in) wide between 5 cm (2.0 in) wide arm rests. Airbus states that the seat will be 1.3 cm (0.5 in) wider than a 787 seat in the equivalent configuration.

In the nine-abreast, 3–3–3 standard economy layout, the A350 seat will be 45 cm (18 in) wide, 1.27 cm (0.5 in) wider than a seat in the equivalent layout in the 787,[142] and 3.9 cm (1.5 in) wider than a seat in the equivalent A330 layout.[143] The current 777 and future derivatives have 1.27 cm (0.5 in) greater seat width than the A350 in a nine-abreast configuration.[144][145][146] The 10-abreast seating on the A350 is similar to a 9-abreast configuration on the A330, with a seat width of 41.65 cm (16.4 in).[21][147] Overall, the A350 gives passengers more headroom, larger overhead storage space, and wider panoramic windows than current Airbus models.

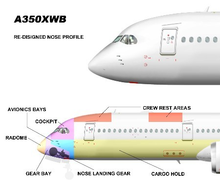

The A350 nose section has a configuration derived from the A380 with a forward-mounted nosegear bay and a six-panel flightdeck windscreen.[148] This differs substantially from the four-window arrangement in the original A350 XWB design.[149] The new nose, made of aluminium,[150] improves aerodynamics and enables overhead crew rest areas to be installed further forward and eliminate any encroachment in the passenger cabin. The new windscreen has been revised to improve vision by reducing the width of the centre post. The upper shell radius of the nose section has been increased.[151]

The Airbus A350 initially featured manual window shades. In 2020, Airbus announced that dimmable windows, similar to those on the Boeing 787, would be offered as an option.[152] These windows are designed to darken or lighten more efficiently, providing greater control over light levels while maintaining an outside view.[citation needed] Starlux Airlines became the first carrier to receive A350s equipped with dimmable windows across all cabins, while Japan Airlines offers this feature exclusively in premium economy and higher-class cabins, retaining manual shades for economy passengers.[153]

Wing

[edit]

The A350 features new composite wings with a wingspan that is common to the proposed variants.[154] Its 64.75 m (212.4 ft) wingspan stays within the same ICAO Aerodrome Reference Code E 65 m limit as the A330/A340[155] and the Boeing 777.[156] The A350's wing has a 31.9° sweep angle for a Mach 0.85 cruise speed and has a maximum operating speed of Mach 0.89.[157]

The -900 wing has an area of 442 m2 (4,760 sq ft).[158] This is between the 436.8 m2 (4,702 sq ft) wing of the current Boeing 777-200LR/300ER and the 466.8 m2 (5,025 sq ft) wing of the in-development Boeing 777X.[159] However, Boeing and Airbus do not use the same measurement.[160] The A350-1000 wing is 22.3 m2 (240 sq ft) larger through a 30 cm (12 in) extension to the inboard sections of the fixed trailing edge.[161]

A new trailing-edge high-lift device has been adopted with an advanced dropped-hinge flap similar to that of the A380, which permits the gap between the trailing edge and the flap to be closed with the spoiler.[162] It is a limited morphing wing with adaptive features for continuously optimising the wing loading to reduce fuel burn: variable camber for longitudinal load control where inboard & outboard flaps deflect together and differential flaps setting for lateral load control where inboard & outboard flaps deflect differentially.[163]

The manufacturer has extensively used computational fluid dynamics and also carried out more than 4,000 hours of low- and high-speed windtunnel testing to refine the aerodynamic design.[164] The final configuration of wing and winglet was achieved for the "Maturity Gate 5" on 17 December 2008.[165] The wingtip device curves upwards over the final 4.4 m (14 ft).[139] The wings are produced in the new £400 million (US$641M), 46,000 m2 (500,000 sq ft) North Factory at Airbus Broughton, employing 650 workers, in a specialist facility constructed with £29M of support from the Welsh Government.[166]

Undercarriage

[edit]Airbus adopted a new philosophy for the attachment of the A350's main undercarriage as part of the switch to a composite wing structure. Each main undercarriage leg is attached to the rear wing spar forward and to a gear beam aft, which itself is attached to the wing and the fuselage. To help reduce the loads further into the wing, a double side-stay configuration has been adopted. This solution resembles the design of the Vickers VC10.[167]

Airbus devised a three-pronged main undercarriage design philosophy encompassing both four- and six-wheel bogies to stay within pavement loading limits. The A350-900 has four-wheel bogies in a 4.1 m (13 ft) long bay. The higher weight variant, the A350-1000 uses a six-wheel bogie, with a 4.7 m (15 ft) undercarriage bay.[168] French-based Messier-Dowty provides the main undercarriage for the -900 variant, with titanium forgings from Kobelco,[169][170] and UTC Aerospace Systems supplies the -1000 variant. The nose gear is supplied by Liebherr Aerospace.[171]

-

The A350-900 has a four-wheel main gear for a 283 t (624,000 lb) MTOW.

-

The A350-1000 has a six-wheel main landing gear to support a 322 t (710,000 lb) MTOW.

Systems

[edit]Honeywell supplies its 1,700 horsepower (1,300 kW) HGT1700 auxiliary power unit with 10% greater power density than the TPE331 from which it is developed, and the air management system: the bleed air, environmental control, cabin pressure control and supplemental cooling systems.[172] Airbus says that the new design provides a better cabin atmosphere with 20% humidity, a typical cabin altitude at or below 6,000 ft (1,800 m) and an airflow management system that adapts cabin airflow to passenger load with draught-free air circulation.[173]

The ram air turbine, with a nominal power of 50 kilovolt-ampere,[174] is supplied by Hamilton Sundstrand and located in the lower surface of the fuselage.[175] In light of the 787 Dreamliner battery problems, in February 2013 Airbus decided to revert from lithium-ion to the proven nickel-cadmium technology although the flight test programme will continue with the lithium-ion battery systems.[176] In late 2015, A350 XWB msn. 24 was delivered with 80 kg (176 lb) lighter Saft Li-ion batteries and in June 2017, fifty A350s were flying with them and benefiting from a two-year maintenance schedule instead of NiCd's 4–6 months.[177]

Parker Hannifin supplies the complete fuel package: inerting system, fuel measurement and management systems, mechanical equipment and fuel pumps. The fuel tank inerting system features air-separation modules to generate nitrogen-enriched air to reduce the flammability of fuel vapour in the tanks. Parker also provides hydraulic power generation and distribution system: reservoirs, manifolds, accumulators, thermal control, isolation, software and new engine- and electric motor-driven pump designs. Parker estimates the contracts will generate more than US$2 billion in revenues over the life of the programme.[178]

Cockpit and avionics

[edit]

The revised design of the A350 XWB's glass cockpit dropped the A380-sized display and adopted 38 cm (15 in) liquid-crystal display screens. The new six-screen configuration includes two central displays mounted one above the other (the lower one above the thrust levers) and a single (for each pilot) primary flight/navigation display, with an adjacent on-board information system screen driven by laptops running EFB software which are connected while stowed behind each pilot.[179][180] Airbus says the cockpit design allows for future advances in navigation technology to be placed on the displays plus gives flexibility and capacity to upload new software and to combine data from multiple sources and sensors for flight management and aircraft systems control.[181] An optional head-up display is also present in the cockpit.

Avionics are a further development of the integrated modular avionics (IMA) concept found on the A380. The A350's IMA will manage up to 40 functions (versus 23 functions for the A380) such as undercarriage, fuel, pneumatics, cabin environmental systems, and fire detection.[149][181] Airbus stated that the benefits includes reduced maintenance and lower weight because as the IMA replaces multiple processors and LRUs with around 50% fewer standard computer modules known as line-replaceable modules. The IMA runs on a 100 Mbit/s network based on the Avionics Full-Duplex Switched Ethernet standard, as employed in the A380, in place of the architecture used on the A330/A340.

Propulsion

[edit]

In 2005, GE was the launch engine of the original A350, aiming for 2010 deliveries, while Rolls-Royce offered its Trent 1700. For the updated A350 XWB, GE offered a 87,000 lbf (390 kN) GEnx-3A87 for the A350-800/900, but not a higher thrust version needed for the A350-1000, which competes with the longer range 777 powered exclusively with the GE90-115B. In December 2006, Rolls-Royce was selected for the A350 XWB launch engine.[133]

The Rolls-Royce Trent XWB features a 300 cm (118 in) diameter fan and the design is based on the advanced developments of the Airbus A380 Trent 900 and the Boeing 787 Trent 1000. It has four thrust levels to power the A350 variants: 75,000 lbf (330 kN) and 79,000 lbf (350 kN) for the regional variants of the A350-900 while the baseline A350-900 has the standard 84,000 lbf (370 kN) and 97,000 lbf (430 kN) for the A350-1000.[182] The higher-thrust version will have some modifications to the fan module—it will be the same diameter but will run slightly faster and have a new fan blade design—and run at increased temperatures allowed by new materials technologies from Rolls-Royce's research.[183]

The Trent XWB may also benefit from the next-generation reduced acoustic mode scattering engine duct system (RAMSES), an acoustic quieting engine nacelle intake, and a carry-on design of the Airbus's "zero splice" intake liner developed for the A380.[184] A "hot and high" rating option for Middle Eastern customers Qatar Airways, Emirates, and Etihad Airways keep its thrust available at higher temperatures and altitudes.

Airbus aimed to certify the A350 with 350-minute ETOPS capability on entry into service;[185] although Airbus achieved a 370-minute ETOPS rating on 15 October 2014, which covers 99.7% of the Earth's surface.[186] There are plans to extend this to 420 minutes in the future.[187] Engine thrust-reversers and nacelles are supplied by US-based Collins Aerospace (formerly UTC Aerospace Systems).[188][189]

Operational history

[edit]

One year after introduction, the A350 fleet had accumulated 3,000 flight cycles and around 16,000 block hours. Average daily usage by first customers was 11.4 hours with flights averaging 5.2 hours, which are under the aircraft's capabilities and reflect both short flights within the schedules of Qatar Airways and Vietnam Airlines, as well as flight-crew proficiency training that is typical of early use and is accomplished on short-haul flights. Finnair was operating the A350 at very high rates: 15 flight hours per day for Beijing, 18 hours for Shanghai, and more than 20 hours for Bangkok.[190] This may have accelerated the retirement of the Airbus A340.[190]

In service, problems occurred in three areas. The onboard maintenance, repair, overhaul network needed software improvements. Airbus issued service bulletins regarding onboard equipment and removed galley inserts (coffee makers, toaster ovens) because of leaks. Airbus had to address spurious overheating warnings in the bleed air system by retrofitting an original connector with a gold-plated connector. Airbus targeted a 98.5% dependability by the end of 2016 and to match the mature A330 reliability by early 2019.[190]

By the end of May 2016, the A350 fleet had flown 55,200 hours over 9,400 cycles at a 97.8% operational reliability on three months. The longest operated sector was Qatar Airways' Adelaide–Doha at 13.8 hours for 6,120 nmi (11,334 km; 7,043 mi). 45% of flights were under 3,000 nmi (5,556 km; 3,452 mi), 16% over 5,000 nmi (9,260 km; 5,754 mi), and 39% in between. The average flight was 6.8 hours, with the longest average being 9.6 hours by TAM Airlines and the shortest being 2.1 hours by Cathay Pacific's. It is able to seat from 253 seats for Singapore Airlines to 348 seats for TAM Airlines, with a 30 to 46 seat business class and a 211 to 318 seat economy class, often including a premium economy.[191] A total of 49 A350s were delivered to customers in 2016. It was also planned that the monthly rate would grow to 10 by the end of 2018, which was eventually achieved in 2019 when Airbus delivered 112 aircraft over a period of 11 months.[192][69]

In January 2017, two years after introduction, 62 aircraft were in service with 10 airlines. They had accumulated 25,000 flights over 154,000 hours with an average daily utilisation of 12.5 hours, and transported six million passengers with a 98.7% operational reliability.[193] Zodiac Aerospace encountered production difficulties with business class seats in their Texas and California factories. After a year, Cathay Pacific experienced cosmetic quality issues and upgraded or replaced the seats for the earliest cabins.[194] In 2017, average test flights before delivery decreased to 4.1 from 12 in 2014, with an average delay down to 25 days from 68.[195] Its reliability was 97.2% in 2015, 98.3% in 2016, and 98.8% in June 2017, just behind its 99% target for 2017.[196]

In June 2017 after 30 months in commercial operation, 80 A350s were in service with 12 operators, the largest being Qatar Airways with 17 and 13 each at Cathay Pacific and Singapore Airlines (SIA).[192] The fleet average block time (time between pushback and destination gate arrival) was 7.2 hours with 53% below 3,000 nmi (5,556 km; 3,452 mi), 16% over 5,000 nmi (9,260 km; 5,754 mi), and 31% in between. LATAM Airlines had the longest average sector at 10.7 hours, and Asiana had the shortest at 3.8 hours.[192] Singapore Airlines operated the longest leg, Singapore to San Francisco 7,340 nmi (13,594 km; 8,447 mi), and the shortest leg, Singapore to Kuala Lumpur 160 nmi (296 km; 184 mi).[192] Seating varied from 253 for Singapore Airlines to 389 for Air Caraïbes, with most between 280 and 320.[192]

As of February 2018, 142 A350-900s had been delivered, and were in operation with a dispatch reliability of 99.3%.[197] As of November 2019, 33 operators had received 331 aircraft from 959 orders, and 2.6 million hours have been flown.[198]

On 30 September 2022, the 500th A350, an A350-900, was delivered to Iberia.[130] As of September 2024[update], the global A350 fleet of 620 aircraft had completed more than 1,589,000 flights on more than 1,240 routes, and had carried more than 400 million passengers since its entry into service; the fleet had 99.3 percent operational reliability in the last 3 months.[199]

Qatar Airways paint dispute

[edit]In August 2021, as several A350s were sent in to be repainted in a scheme advertising the 2022 FIFA World Cup (played in Qatar), Qatar Airways discovered that their paint was unusually degraded. The airline grounded its A350s until the root cause could be determined, and would not accept new aircraft deliveries until the problem could be solved.[200] The European civil aviation regulator, EASA, found that paint degradation did not affect the aircraft structure or introduce "other risks".[201] The Qatari civil aviation regulator was the only one that agreed with the airline that it was an airworthiness issue.[202]

In November 2021, Reuters found that Finnair, Cathay Pacific, Etihad, Lufthansa and Air France had also complained of paint damage as early as 2016.[203] Singapore Airlines had not detected such problems with its fleet.[204]

On 20 December 2021, Airbus received a formal legal claim in the English courts filed by Qatar Airways.[205] Qatar Airways alleged that the surface flaws cause the risk of fuel tank ignition due to the degradation in lightning protection over the fuel tanks in the wings.[206] Qatar Airways claimed it was owed US$200,000 per day in compensation for each grounded aircraft.[202] Meanwhile, according to a Flight International editorial, Airbus's decision to cancel Qatar's outstanding orders indicated that it was certain of its case.[202] The court hearing was originally scheduled for summer 2023.[207]

Both Airbus and Qatar Airways agreed to settle the dispute on 1 February 2023.[208] While the settlement was confidential, Flight International believed that Airbus achieved a more favourable outcome, opining that there was no major impact to Airbus's finances, the A350's reputation remained intact and Qatar's A321neos would nevertheless be delivered.[202]

Variants

[edit]

The three main variants of the A350 were launched in 2006, with entry into service planned for 2013.[26] At the 2011 Paris Air Show, Airbus postponed the entry into service of the A350-1000 by two years to mid-2017.[85] In July 2012, the A350's entry into service was delayed to the second half of 2014,[86] before the -900 began service on 15 January 2015.[3] In October 2012, the -800 was due to enter service in mid-2016,[209] but its development was cancelled in September 2014 in favour of the reengined Airbus A330neo.[99] The A350 is also offered as the ACJ350 corporate jet by Airbus Corporate Jets (ACJ), offering a 20,000 km; 12,400 mi (10,800 nmi) range for 25 passengers for the -900 derivative.[210]

A350-900

[edit]

The A350-900 (ICAO code: A359) is the first A350 model; it has a MTOW of 280 tonnes (620,000 lb),[211] typically seats 325 passengers, and has a range of 8,100 nmi (15,000 km; 9,300 mi).[212] Airbus says that per seat, the Boeing 777-200ER should have a 16% heavier manufacturer's empty weight, a 30% higher block fuel consumption, and 25% higher cash operating costs than the A350-900.[213] The −900 is designed to compete with the Boeing 777-200LR and 787-10,[214] while replacing the Airbus A340-500.

A proposed A350−900R extended-range variant was to feature the higher engine thrust, strengthened structure, and landing gear of the 308 tonnes (679,000 lb) MTOW -1000 to give a further 800 nmi (1,500 km; 920 mi) range.[215]

Philippine Airlines (PAL) will replace its A340-300 with an A350-900HGW ("high-gross weight") variant available from 2017.[216] It will enable non-stop Manila-New York City flights without payload limitations in either direction,[217] a 7,404 nmi (13,712 km; 8,520 mi) flight.[218] The PAL version will have a 278 tonnes (613,000 lb) MTOW, and from 2020, the -900 will be proposed with the ULR's 280 tonnes (620,000 lb) MTOW, up from the 268 tonnes (591,000 lb) for the original weight variant and the certified 260, 272, and 275 tonnes (573,000, 600,000, and 606,000 lb) variants, with the large fuel capacity. This will enable an 8,100 nmi (15,000 km; 9,300 mi) range with 325 seats in a three-class layout.[219]

In early November 2017, Emirates committed to purchase 40 Boeing 787-10 aircraft before Airbus presented an updated A350-900 layout with the rear pressure bulkhead pushed back by 2.5 ft (1 m).[220] After Emirates' Tim Clark was shown a ten-abreast economy cabin and galley changes, he said the -900 is "more marketable" as a result.[221]

The average lease rates of the first A350-900s produced in 2014 were $1.1 million per month, not including maintenance reserves amounting to $18 million after 10–12 years, and falling to $940,000 per month in 2018 while a new A350-900 is leased for $1.2 million per month and its interior can cost $12 million, 10% of the aircraft.[222] By 2018, a 2014 build was valued $108M falling to $74.5M by 2022 while a new build was valued for $148M, a 6+12year check cost $3M and an engine overhaul $4–6.5M.[223]

A350-900ULR

[edit]

The MTOW of the ultra-long range -900ULR has been increased to 280 t (620,000 lb) and its fuel capacity increased from 141,000 to 165,000 L (37,000 to 44,000 US gal) within existing fuel tanks, enabling up to 19-hour flights with a 9,700 nmi (18,000 km; 11,200 mi) range,[224] the longest range of any airliner in service as of 2023[update].[199] The MTOW is increased by 5 tonnes (11,000 lb) from the previously certified 275 tonnes (606,000 lb) variant.[211] Because of the A350-900's fuel consumption of 5.8 tonnes (13,000 lb) per hour, it needs an additional 24 tonnes (53,000 lb) of fuel to fly 19 hours instead of the standard 15 hours: the increased MTOW and lower payloads will enable the larger fuel capacity.[225] Non-stop flights could last more than 20 hours.[226] The first −900ULR was rolled out without its engines in February 2018 for ground testing. Flight-tests after engine installation checked the larger fuel capacity and measured the performance improvements from the extended winglets.[227] It made its first flight on 23 April 2018.[228]

Singapore Airlines, the launch customer and currently the only operator, uses its seven -900ULR aircraft on non-stop flights between Singapore and New York City and cities on the U.S. west coast.[citation needed] Singapore Airlines' seating is to range from 170 in largely business class seating up to over 250 in mixed seating.[229] The planes can be reconfigured.[230] They will have two seating classes.[231] The airline received its first -900ULR on 23 September 2018, with 67 business class seats and 94 premium economy seats.[232] On 12 October 2018, it landed the world's then-longest flight at Newark Liberty International Airport from Singapore Changi after 17 hours and 52 minutes,[233] covering 16,561 kilometres (8,942 nmi; 10,291 mi) for a 15,353 kilometres (8,290 nmi; 9,540 mi) orthodromic distance.[234] It burned 101.4 t (224,000 lb) of fuel to cover the route in 17 h 22 min: an average of 5.8 tonnes per hour (1.6 kg/s).[235] As of 2022, the A350-900ULR is used on the longest flight in the world, Singapore Airlines Flights 23 and 24 from Singapore to New York JFK.

At the 2015 Dubai Air Show, John Leahy noted the demand of the Persian Gulf airlines for this variant.[236] In February 2018, Qatar Airways stated its preference for the larger -1000, having no need for the extra range of the -900ULR.[237] Compared to the standard -900, the -900ULR additional value is likely around $2 million.[238]

ACJ350

[edit]

Airbus Corporate Jet version of the A350, the ACJ350, is derived from the A350-900ULR. As a result of the increased fuel capacity from the -900ULR, the ACJ350 has a maximum range of 20,000 km (10,800 nmi; 12,430 mi).[239] The German Air Force is to be the first to receive the ACJ350, having ordered three aircraft which will replace its two A340-300s.[240]

A350 Regional

[edit]After the Boeing 787-10 launch at the 2013 Paris Air Show, Airbus discussed with airlines a possible A350-900 Regional with a reduced MTOW of 250 t (550,000 lb).[241] Engine thrust would have been reduced to 70,000–75,000 lbf (310–330 kN) from the standard 85,000 lbf (380 kN) and the variant would have been optimised for routes up to 6,800 nmi (12,600 km; 7,800 mi) with seating for up to 360 passengers in a single-class layout.[242] The A350 Regional was expected to be ordered by Etihad Airways[243] and Singapore Airlines.[244] Since 2013, there has been no further announcement about this variant.

Singapore Airlines selected an A350-900 version for medium-haul use,[245] and Japan Airlines took delivery of a 369-seat A350-900 with a 217 t (478,000 lb) MTOW for its domestic flight network.[246] The A350 Type Certificate Data Sheet includes MTOWs of 217, 235, 240, 250, 255, 260, 268, 272, 275, 277, 278, 280 and 283 t.[112]

A350-1000

[edit]

The A350-1000 (ICAO code: A35K) is the largest variant of the A350 family at just under 74 metres (243 ft) in length. It seats 350–410 passengers in a typical three-class layout with a range of 8,700 nmi (16,100 km; 10,000 mi).[247] With a 9-abreast configuration, it is designed to replace the A340-600 and compete with the Boeing 777-300ER and 777-8. Airbus estimates a 366-seat -1000 should have a 35 tonnes (77,000 lb) lighter operating empty weight than a 398-seat 777-9, a 15% lower trip cost, a 7% lower seat cost, and a 400 nmi (740 km; 460 mi) greater range.[248] Compared to a Boeing 777-300ER with 360 seats, Airbus claims a 25% fuel burn per seat advantage for an A350-1000 with 369 seats.[249] The 7 m (23 ft) extension seats 40 more passengers with 40% more premium area.[163] The -1000 can match the 40 more seats of the 777-9 with a 10-abreast seating configuration but diminished comfort.[250]

The A350-1000 has an 11-frame stretch over the −900 and a slightly larger wing than the −800/900 models with trailing-edge extension increasing its area by 4%. This will extend the high-lift devices and the ailerons, making the chord bigger by around 400 mm (16 in), optimising flap lift performance as well as cruise performance.[251] The main landing gear is a 6-wheel bogie instead of a 4-wheel bogie, put in a one frame longer bay. The Rolls-Royce Trent XWB engine's thrust is augmented to 97,000 lbf (430 kN).[252] These and other engineering upgrades are necessary so that the −1000 model maintains range.[253]

It features an automatic emergency descent function to around 10,000 ft (3,000 m) and notifies air traffic control if the crew fails to respond to an alert, indicating possible incapacitation from depressurisation. The avionics software adaptation is activated by a push and pull button to avoid mistakes and could be retrofitted in the smaller -900.[254] All performance targets have been met or exceeded, and it remains within its weight specification, unlike early −900s.[113]

Its basic 308 t (679,000 lb) MTOW was increased to 311 t (686,000 lb) before offering a possible 316 t (697,000 lb) version.[255] Its 316 t MTOW appeared on 29 May 2018 update of its type certificate data sheet.[112] This raised its range from 7,950 to 8,400 nmi (14,720 to 15,560 km; 9,150 to 9,670 mi).[256] A further MTOW increase by 3 t (6,600 lb), to a total of 319 t (703,000 lb) is under study to be available from 2020 and could be a response to Qantas' Project Sunrise.[257]

In November 2019, maximum accommodation increased to 480 seats from 440 through the installation of new "Type-A+" exits, with a dual-lane evacuation slide.[258] On 17 December 2021, French Bee took delivery of the first A350-1000 in this 480-seat configuration, leased by Air Lease Corporation and to be operated by from Paris to Reunion Island, with 40 premium and 440 economy seats.[259]

In October 2023, the variant's MTOW was raised again to 322 t (710,000 lb).[260]

Qantas Project Sunrise

[edit]In December 2019, Qantas tentatively chose the A350-1000 to operate their Project Sunrise routes, before a final decision in March 2020 for up to 12 aircraft.[261] Initial speculation suggested that the variant might be marketed as the A350-1000ULR.[262] However, the -1000 is not expected to share the -900ULR's larger fuel tanks and other fuel system modifications, and Airbus has stopped short of describing the largest MTOW variant as a ULR model, despite the 8,700 nmi (16,100 km; 10,000 mi) range.[263] After a delay due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the decision was confirmed on 2 May 2022, when Qantas placed a formal order for 12 Airbus A350-1000 aircraft for Project Sunrise flights to originally start in 2025.[264]

On 6 June 2024, Qantas International CEO Cam Wallace, confirmed at the 80th International Air Transport Authority (IATA) AGM in Dubai, that the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) had approved the design of the rear centre tank (RCT) that allowed the aircraft to fly the distances required, following a requested redesign.[265] With Airbus integrating the tank into the A350-1000 for flight testing in early 2025 for delivery to the group in mid-2026. The aircraft will be configured with 238 seats in four classes,[266] with Qantas publications and website using the ULR abbreviation, but Airbus is yet to confirm.[267]

A350F

[edit]

An A350-900 freighter was first mentioned in 2007, offering a similar capacity to the MD-11F with a range of 9,250 km (5,000 nmi; 5,750 mi), to be developed after the passenger version.[268] In early 2020, Airbus was proposing an A350F before a potential launch.[269] The proposed freighter would be slightly longer than the A350-900 and Airbus would need 50 orders to launch the $2–3 billion programme.[270] In July 2021, the Airbus board approved the freighter development.[271] It is based on the -1000 version for a payload over 90 tonnes, and entry into service is targeted for 2025.[272]

The A350F would keep the 319-tonne MTOW previously announced for the A350-1000 on a shortened fuselage, but the proposed design remains 6.9 m (23 ft) longer than the Boeing 777F with 10% larger freight volume at 695 m3 (24,500 cu ft).[273][260] With a main deck cargo door behind the wing and reinforced main deck aluminium floor beams, its 111 t (245,000 lb) payload is higher than the 103.7 t (229,000 lb) of the 777F, while its empty weight is 30 tonnes (66,000 lb) lighter than the A350-1000, 20 tonnes (44,000 lb) lighter than the 777F.[273][274] The 70.8 m (232 ft) long cargo variant should have a 4,700 nmi (8,700 km; 5,400 mi) range at max payload.[275] At the November 2021 Dubai Air Show, US lessor Air Lease Corporation became the launch customer with an order for seven to be delivered around 2026, among other Airbus airliners.[276] The launch operator of the A350F will be Singapore Airlines, who ordered 7 aircraft at the 2022 Singapore Airshow,[277] with deliveries expected to begin in 2026.[274]

Operators

[edit]

There are 627 A350 aircraft in service with 38 operators and 61 customers as of November 2024[update]. The five largest operators were Singapore Airlines (65), Qatar Airways (58), Cathay Pacific (48), Air France (35) and Delta Air Lines (34).[1][198]

Orders and deliveries

[edit]The A350 family has 1,345 firm orders from 61 customers, of which Turkish Airlines is the largest with 110 orders. A total of 628 aircraft have been delivered as of November 2024[update].[1]

In June 2023, the A350 family aircraft reached 1,000 orders.[1]

| Type | Orders | Deliveries | Backlog |

| A350-900 | 988 | 538 | 450 |

| A350-1000 | 302 | 90 | 212 |

| A350F | 55 | – | 55 |

| A350 family | 1,345 | 628 | 717 |

| 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | Total | ||

| Orders | 2 | 292[278] | 163[279] | 51 | 78 | −31 | 27 | 230 | −32 | −3 | 41 | 36 | 40 | 32 | −11 | 2 | 8 | 281 | 139 | 1,345 | |

| Deliveries | A350-900 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | 14 | 49 | 78 | 79 | 87 | 45 | 49 | 50 | 52 | 34 | 538 |

| A350-1000 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 14 | 25 | 14 | 6 | 10 | 12 | 9 | 90 | |

| A350F | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0 | |

| A350 family | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | 14 | 49 | 78 | 93 | 112 | 59 | 55 | 60 | 64 | 43 | 628 | |

|

Accidents and incidents

[edit]The A350 fleet has been involved in one airport-safety related hull-loss accident as of December 2024[update]. Although there were no fatalities onboard the A350, there were five fatalities onboard another aircraft on the ground.[280][281]

- On 2 January 2024, Japan Airlines Flight 516, an A350-900 flying from New Chitose Airport in Hokkaido to Haneda Airport in Tokyo, collided after touchdown with a De Havilland Canada Dash 8 operated by the Japan Coast Guard. The A350 caught fire and was completely destroyed, though all 367 passengers and 12 crew members successfully evacuated from the aircraft with 17 injuries reported. Five of the six crew members aboard the Coast Guard aircraft were killed; the sole survivor was the captain, who escaped with serious injuries.[282][283] The Japan Coast Guard aircraft it collided with was participating in relief efforts following the Noto earthquake the previous day.[284] Flight 516 had been cleared to land by Haneda ATC when it struck the coast guard plane.[285]

Specifications

[edit]| Model | A350-900/-900ULR[287] | A350-1000[287] | A350F[275] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cockpit crew | Two | ||

| Typical seating | 315 (48J+267Y) | 369 (54J+315Y) | 11 |

| Main deck max.[112] | 440 seats | 480 seats | 30 pallets 96 x 125’’ |

| Lower deck Cargo | 36 LD3 or 11 pallets | 44 LD3 or 14 pallets | 40 LD3 or 12 pallets |

| Overall length | 66.8 m (219.2 ft) | 73.79 m (242.1 ft) | 70.8 m (232.2 ft) |

| Wing | 64.75 m (212.43 ft) span, 31.9° sweep[157] | ||

| Aspect ratio | 9.49 | 9.03 | |

| Wing area | 442 m2 (4,760 sq ft)[158] | 464.3 m2 (4,998 sq ft)[161] | |

| Overall height | 17.05 m (55 ft 11 in) | 17.08 m (56 ft 0 in) | |

| Fuselage | 5.96 m (19.6 ft) width, 6.09 m (19.98 ft) height | ||

| Cabin width | 5.61 m (18 ft 5 in) with 18-inch-wide (46 cm), 9-abreast seating[212][288] 5.71 m (18 ft 9 in) with 16.8-inch-wide (43 cm), 10-abrest seating[289][290] | ||

| MTOW | 283 t (623,908 lb) ULR: 280 t (620,000 lb) |

322 t (710,000 lb)[260] | 319 t (703,000 lb) |

| Max. payload | 53.3 t (118,000 lb) 45.9–56.4 t (101,300–124,300 lb)[157] |

67.3 t (148,000 lb) | 111 t (245,000 lb)[291] |

| Fuel capacity[112] | 140.8 m3 (37,200 US gal) 110.5 t (244,000 lb)[a] ULR: 170 m3 (44,000 US gal) |

158.8 m3 (42,000 US gal) 124.65 t (274,800 lb) | |

| OEW | 142.4 t (314,000 lb) typical 134.7–145.1 t (297,000–320,000 lb)[157] |

155 t (342,000 lb) dry[292] | 124.4 t (274,000 lb)[b] 131.7 t (290,000 lb)[c] |

| MEW | 115.7 t (255,075 lb)[295] | 129 t (284,000 lb)[197] | |

| Engines (2×) | Rolls-Royce Trent XWB | ||

| Max. thrust (2x)[112] | 84,200 lbf (374.5 kN) | 97,000 lbf (431.5 kN) | |

| Cruise speed | Mach 0.85 (488 kn; 903 km/h; 561 mph) typical Mach 0.89 (513 kn; 950 km/h; 591 mph) max.[157] | ||

| Range | 8,300 nmi (15,372 km; 9,600 mi)[d][a] ULR: 9,700 nmi (17,964 km; 11,163 mi)[297] |

8,900 nmi (16,500 km; 10,200 mi)[d][298] | 4,700 nmi (8,700 km; 5,400 mi)[e] |

| Takeoff (MTOW, SL, ISA) | 2,600 m (8,500 ft) | ||

| Landing (MLW, SL, ISA) | 2,000 m (6,600 ft) | ||

| Service ceiling[112] | 43,100 ft (13,100 m) | 41,450 ft (12,630 m) | |

Aircraft type designations

[edit]| Model[112] | Certification Date | Engines |

|---|---|---|

| A350-941[note 1] | 30 September 2014 | Rolls Royce Trent XWB-75 |

| A350-941/A350-941ULR | 30 September 2014 | Rolls Royce Trent XWB-84 |

| A350-1041 | 21 November 2017 | Rolls Royce Trent XWB-97 |

ICAO aircraft type designators

[edit]| Designation[299] | Type |

|---|---|

| A359 | Airbus A350-900 |

| A35K | Airbus A350-1000 |

See also

[edit]Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h "Airbus O&D". Airbus S.A.S. 30 November 2024. Retrieved 6 December 2024.

- ^ "German Airbus A350 XWB Production commences" (Press release). Airbus S.A.S. 31 August 2010. Archived from the original on 3 October 2012. Retrieved 23 May 2011.

- ^ a b c "A350 enters service as Qatar jet heads for Frankfurt". Flight International. 15 January 2015. Archived from the original on 15 January 2015. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- ^ a b "Airbus Airbus A350 makes maiden test flight". BBC. 14 June 2013. Archived from the original on 17 October 2018. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Gunston 2009, p. 253

- ^ "A350 Receives Authorisation To Offer(ATO)" (Press release). Airbus. 10 December 2004. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ Norris, Guy (14 September 2005). "Qatar signs MoU to launch GEnx on A350". Flightglobal. Archived from the original on 15 April 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ^ "Airbus unleashes A350 for long-range twin dogfight". Flight International. 15 June 2005. Archived from the original on 23 January 2013. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ^ "A350 lifts off with $15bn Qatar". Flightglobal. 14 June 2005. Archived from the original on 17 October 2014.

- ^ Brierley, David (18 June 2006). "Pressure mounts following attack by Emirates". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 23 June 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2011.

- ^ Thomas, Geoffrey (9 May 2006). "Airbus settling on wider fuselage, composite wing as it nears A350 revamp decision". ATW Online. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011.

- ^ Gates, D. "Airplane kingpins tell Airbus: Overhaul A350" Archived 7 April 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Seattle Times, 29 March 2006

- ^ Hamilton, S. "Redesigning the A350: Airbus' tough choice" Archived 27 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Leeham Company

- ^ Michaels, D. and Lunsford, J.L. "Singapore Airlines Says Airbus Needs to Make A350 Improvements" Archived 13 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine. The Wall Street Journal, 7 April 2006

- ^ Associated Press. "Airbus Considering Improvements to A350" Archived 12 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Seattle Times, 10 April 2006.

- ^ "Airbus Considering Improvements to A350" Archived 28 April 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Associated Press, 10 April 2006.

- ^ "Under Pressure, Airbus Redesigns A Troubled Plane". The Wall Street Journal. 14 July 2006. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ^ a b Hepher, Tim (22 December 2014). "Insight - Flying back on course: the inside story of the new Airbus A350 jet". Reuters. Reuters UK. Archived from the original on 25 December 2014. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ^ Gunston 2009, p. 254

- ^ "Singapore Airlines Orders 20 Airbus A350 XWB-900s and 9 Airbus A380s". Businesswire.com. 21 July 2006. Archived from the original on 22 October 2013. Retrieved 18 October 2013.

- ^ a b "Onboard well-being". Airbus S.A.S. Archived from the original on 3 April 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2011.

- ^ Max Kingsley-Jones (19 May 2008). "PICTURE: 10-abreast A350 XWB 'would offer unprecedented operating cost advantage'". Flight International. Archived from the original on 1 May 2009. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- ^ Murdo Morrison (5 April 2016). "Interiors: Why nine is the magic number on the 787". Flight international. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- ^ "Boeing 777: 9 vs 10 Abreast Economy Seating". Airline Reporter. 22 January 2016. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- ^ "Airbus – A350 XWB Xtra comfort". Archived from the original on 5 February 2008.

- ^ a b c "A350 XWB Family receives industrial go-ahead" (Press release). Airbus S.A.S. 1 December 2006. Archived from the original on 3 October 2012. Retrieved 23 May 2011.

- ^ Guy Norris; Max Kingsley-Jones (2 October 2006). "A380 delay puts brakes on A350 XWB formal launch at Airbus". Flight International. Archived from the original on 13 October 2007. Retrieved 23 May 2011.

- ^ Peter Dinkloh (5 October 2006). "Airbus May Stop Work on Its A350 Plane, FT Deutschland Says". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2011.

- ^ "Pegasus orders A350 XWBs, A330-200s". ATWonline.com. 5 January 2007. Archived from the original on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- ^ "Airbus A350 Cost Rises to $15.4 Billion on Composites". Bloomberg. 4 December 2006 Archived 30 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ [1] Archived 9 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine Reuters

- ^ "15 bln U.S dollars for Airbus A350 دیدئو dideo". dideo - search and watch ultimate video. Archived from the original on 27 May 2021.

- ^ Goold, Ian. "A350 Delay Pushes EIS to First Half of 2014". Aviation International News. Archived from the original on 22 February 2020. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- ^ Norris, Guy (8 May 2006). "Airline criticism of Airbus A350 forces airframer to make radical changes to fuselage, wing and engines". Flight International. Archived from the original on 30 August 2007. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- ^ "Airbus rolls out XWB design revisions" Archived 13 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Flight International, September 2001

- ^ "Airbus is at a crossroads on A350 design says ILFC" Archived 13 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Flight International, March 2006.

- ^ Kingsley-Jones, Max (28 September 2007). "Metallic strips will ensure electrical continuity in A350 carbon". Flightglobal. Archived from the original on 5 October 2007.

- ^ "PICTURE: Airbus builds 'physical mock-up' of XWB fuselage to avoid A380 mistakes". Flight International. Archived from the original on 3 May 2010. Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- ^ Steinke, S. "Airbus Unveils A350 XWB". Flug Revue. September 2006.

- ^ Norris, Guy (25 July 2006). "Farnborough: Airbus A350 powerplant race ignites as Rolls-Royce reaches agreement to supply Trent". Flight International. Archived from the original on 29 August 2007.

- ^ Patent 20090277445: System For Improving Air Quality In An Aircraft Pressure Cabin Archived 4 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine AIRBUS DEUTSCHLAND GMBH

- ^ "R-R prepares to ground-test Trent XWB ahead of A380 trials next year" Archived 14 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Flight International, 29 April 2010.

- ^ Thomas, Geoffrey (8 March 2007). "No GP7000 for A350 XWB-1000". atwonline.com. Archived from the original on 15 August 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2011.

- ^ Doyle, Andrew (20 February 2008). "Singapore 2008: Pratt & Whitney pushes GP7000 as alternative A350 XWB engine". Flight International. Archived from the original on 8 May 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ^ Norris, Guy. "GEnx variant may yet power A350" Archived 16 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Flight International, 24 April 2007.

- ^ Norris, Guy (20 April 2007). "Airbus lobbies General Electric to offer GEnx for A350 XWB". Flight International. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- ^ "Airbus Says No To GEnx For A350 XWB". Aero-news.net. 7 June 2007. Archived from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 23 May 2011.

- ^ Ostrower, Jon (7 May 2009). "GE revives interest in A350 engine ahead of 787 flight test". Flight International. Archived from the original on 11 May 2009.

- ^ Kaminski-Morrow, David (21 January 2008). "Airbus selects Thales for A350 XWB cockpit avionics". Flightglobal. Archived from the original on 23 January 2008.

- ^ "A350 cockpit offers unprecedented suite of safety tools". Flight International. 2010. Archived from the original on 9 July 2010. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- ^ 2006-03-15T15:50:00+00:00. "Pictures: Airbus A350 interiors featuring BMW 'help' to be revealed next month". Flight Global. Archived from the original on 22 February 2020. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Honeywell wins Airbus A350 XWB systems contract". Flightglobal. Archived from the original on 10 April 2008. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ^ Kingsley-Jones, Max (12 June 2008). "Streamlined build plan will cut A350 XWB assembly time in half". Flight International. Archived from the original on 13 June 2008. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ^ Kingsley-Jones, Max (13 February 2009). "Airbus and partners gear up for A350 production". Flight International. Archived from the original on 15 February 2009. Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- ^ "Airbus invest in A350 XWB wing line". Flight International. 30 March 2007. Archived from the original on 10 October 2008. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

- ^ "£28 m investment at Airbus factory". BBC. 19 June 2009. Archived from the original on 22 June 2009. Retrieved 23 May 2011.

- ^ Derber, Alex (4 December 2009). "Airbus manufactures first structural component for A350". Flight International. Archived from the original on 7 December 2009.

- ^ "Airbus in Spain begins production of A350 XWB components" (Press release). Airbus. 24 September 2010. Archived from the original on 8 January 2016. Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- ^ Kingsley-Jones, Max (29 July 2010). "Airbus aims to finally start assembling first A350 centre wingbox in August". Flight International. Archived from the original on 1 August 2010. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ^ Kaminski-Morrow, David (1 March 2011). "Airbus opens A350 composite rudder plant in China". Flight International. Archived from the original on 4 March 2011. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ^ "First Airbus A350 Hitches A Ride To the Factory". Wired. 29 December 2011. Archived from the original on 22 December 2016. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ "Airbus starts final assembly of first A350 XWB" (Press release). Airbus. 5 April 2012. Archived from the original on 9 October 2012. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- ^ "First flyable A350 XWB "MSN1" structurally complete" (Press release). Airbus. 4 December 2012. Archived from the original on 7 December 2012.

- ^ "AIRBUS AIRCRAFT 2018 AVERAGE LIST PRICES* (USD millions)" (PDF). Airbus.com. 15 January 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 July 2018. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- ^ "Airbus begins A350 ramp-up towards 10 a month". Flight International. 23 December 2014. Archived from the original on 24 April 2015. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ^ Bjorn Fehrm (23 April 2015). "Bjorn's Corner: Boeing's 787 and Airbus' 350 programs, a snapshot". Leeham News and Comment. Archived from the original on 30 May 2015. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ^ "Airbus preparing to hike A350 production rate". Leeham. 5 October 2017. Archived from the original on 22 February 2018. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ Thierry Dubois (20 February 2018). "Qatar Airways takes delivery of first Airbus A350-1000". Aviation Week Network. Archived from the original on 22 February 2018. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- ^ a b "Orders and deliveries". Airbus. Archived from the original on 10 February 2019. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ^ David Kaminski-Morrow (13 February 2020). "Airbus to cut A330 output and keep A350 rate level". Flightglobal. Archived from the original on 13 February 2020. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

- ^ David Kaminski-Morrow (30 June 2020). "Airbus not expecting significant changes in production rates: Faury". FlightGlobal. Archived from the original on 16 September 2020. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ^ Katz, Benjamin (16 February 2023). "Airbus Boosts Wide-Body Production, Increasing Pressure on Boeing". WSJ. Archived from the original on 16 February 2023. Retrieved 16 February 2023.

- ^ David Kaminski-Morrow (25 April 2024). "Airbus raising monthly A350 production to 12 in response to strong widebody demand". Flightglobal.

- ^ "A350's Trent XWB engine runs for first time". Flightglobal. 18 June 2010. Archived from the original on 21 June 2010.

- ^ "Airbus Powers Up A350 Engines in Preparation for Debut Flight". Business Week. 2 June 2013. Archived from the original on 4 November 2016. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ "Airbus declares A350 maiden flight a success". Financial Times. 14 June 2013. Archived from the original on 16 November 2017. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- ^ Chris Sloan (15 June 2013). "The Airbus A350 XWB: Being There At The Maiden Flight". Airways International. Archived from the original on 9 April 2018. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- ^ "A350: The aircraft that Airbus did not want to build". BBC. 14 June 2013. Archived from the original on 18 July 2018. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ^ "The A350 XWB goes "hot and cold" during climatic testing in Florida" (Press release). Airbus. Archived from the original on 4 January 2015.

- ^ "Airbus A350-900 receives EASA Type Certification" (Press release). Airbus. 30 September 2014. Archived from the original on 3 October 2014. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ^ "EASA certifies Airbus A350 XWB for up to 370 minute ETOPS" (Press release). European Aviation Safety Agency. 15 October 2014. Archived from the original on 20 October 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ^ "The Common Type Rating is approved for A350 XWB and A330 pilot training" (Press release). Airbus. 22 October 2014. Archived from the original on 26 October 2014.

- ^ "Airbus A350-900 receives FAA type certification" (Press release). Airbus. 13 November 2014. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ^ "Airworthiness Directive No.: 2017-0129R1". EASA. 19 July 2019. Archived from the original on 26 July 2019. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- ^ a b "PARIS: A350-1000 delayed to 2017 as Rolls raises XWB thrust". Flightglobal. 19 June 2011. Archived from the original on 10 February 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- ^ a b "Airbus delays A350 XWB entry as EADS profits triple". BBC. 27 July 2012. Archived from the original on 19 August 2018. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ^ "Airbus delivers first ever A350 XWB to Qatar Airways" (Press release). Airbus. 22 December 2014. Archived from the original on 22 December 2014. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- ^ a b "A350-1000 takes off on maiden flight". FlightGlobal. RELX Group. 24 November 2016. Archived from the original on 24 November 2016. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- ^ "Qatar to put first A350-1000 on Heathrow route". Flight International. 20 February 2018. Archived from the original on 11 September 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- ^ "First Airbus A350-1000 of Qatar Airways flies to London as launch destination". The Peninsula Qatar. 25 February 2018. Archived from the original on 25 February 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- ^ "Airbus Family Figures" (PDF). Airbus. May 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 February 2018.

- ^ "A350-800 to be developed as -900 shrink". Flightglobal. 12 January 2010. Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- ^ "Qatar Airways backs Airbus rethink on A350-800 design". Flight International. 15 January 2010. Archived from the original on 10 February 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- ^ "Airbus focuses on family commonality as it begins A350-800 detailed design". FlightGlobal. 28 April 2010. Archived from the original on 23 March 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- ^ "'Most XWB customers' endorse A350-800 rethink: Airbus". Flightglobal. 29 April 2010. Archived from the original on 26 March 2016. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ^ Kingsley-Jones, Max (30 July 2010). "Airbus works to introduce lighter A350 structure with -800 variant". Flight International. Archived from the original on 10 February 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- ^ "TAP Portugal set to defect to A350-900". Flightglobal. 29 July 2011. Archived from the original on 17 March 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- ^ "Airbus Formally Launches A330neo With ALC As First Customer". Aviation Week. 14 July 2014. Archived from the original on 30 June 2015. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- ^ a b "Al Baker expects A350s to be on schedule". Flightglobal. 17 September 2014. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2016.