Melanesians

| |

| Languages | |

|---|---|

| Melanesian languages, Papuan languages, Indonesian, English, English-based creoles, Rabaul Creole German, French | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Christianity, minority traditional Melanesian religion, and Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Aboriginal Australians, Austronesian peoples, Euronesians |

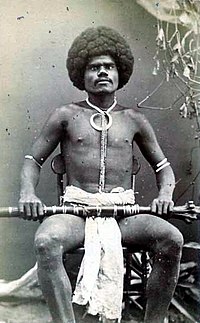

Melanesians are the predominant and indigenous inhabitants of Melanesia, in an area stretching from New Guinea to the Fiji Islands.[1] Most speak one of the many languages of the Austronesian language family (especially ones in the Oceanic branch) or one of the many unrelated families of Papuan languages. There are several creoles of the region, such as Tok Pisin, Hiri Motu, Solomon Islands Pijin, Bislama, and Papuan Malay.[2]

Origin and genetics

[edit]The origin of Melanesians is generally associated with the first settlement of Australasia by a lineage dubbed 'Australasians' or 'Australo-Papuans' during the Initial Upper Paleolithic, which is "ascribed to a population movement with uniform genetic features and material culture" (Ancient East Eurasians), and sharing deep ancestry with modern East Asian peoples and other Asia-Pacific groups.[3][4][5] It is estimated that people reached Sahul (the geological continent consisting of Australia and New Guinea) between 50,000 and 37,000 years ago. Rising sea levels separated New Guinea from Australia about 10,000 years ago. Recent genomic studies suggest that Indigenous Australians and Papuans diverged from Eurasians 51000 to 72000 years ago, and from each other around 25000 to 40000 years ago.[6][5]

The eastern part of Melanesia that includes Vanuatu, New Caledonia, and Fiji, was first inhabited by Austronesian peoples, who created the Lapita culture, and later followed by Melanesian groups. They appear to have occupied these islands as far east as the main islands in the Solomon Islands, including Makira and possibly the smaller islands farther to the east.[7]

Particularly along the north coast of New Guinea and in the islands north and east of New Guinea, the Austronesian people, who had migrated into the area more than 3,000 years ago,[8] came into contact with these pre-existing populations of Papuan-speaking peoples. In the late 20th century, some scholars theorized a long period of interaction, which resulted in many complex changes in genetics, languages, and culture among the peoples.[9] It was proposed that, from this area, a very small group of people (speaking an Austronesian language) departed to the east to become the forebears of the Polynesian people.[10] The indigenous Melanesian populations are thus often classified into two main groups based on differences in language, culture or genetic ancestry: the Papuan-speaking and Austronesian-speaking groups.[11][12]

This Polynesian theory was overturned by a 2010 study, which was based on genome scans and evaluation of more than 800 genetic markers among a wide variety of Pacific peoples. It found that neither Polynesians nor Micronesians have much genetic relation to Melanesians. Both groups are strongly related genetically to East Asians, particularly Taiwanese aborigines. It appeared that, having developed their sailing outrigger canoes, the ancestors of the Polynesians migrated from East Asia, moved through the Melanesian area quickly on their way, and kept going to eastern areas, where they settled. They left little genetic evidence in Melanesia, "and only intermixed to a very modest degree with the indigenous populations there".[11] Nevertheless, the study still found a small Austronesian genetic signature (below 20%) in less than half of the Melanesian groups who speak Austronesian languages, and which was entirely absent in the Papuan-speaking groups.[8][11]

The study found a high rate of genetic differentiation and diversity among the groups living within the Melanesian islands, with the peoples not only distinguished between the islands, but also by the languages, topography, and size of an island. Such diversity developed over the tens of thousands of years since initial settlement, as well as after the more recent arrival of Polynesian ancestors at the islands. Papuan-speaking groups in particular were found to be the most differentiated, while Austronesian-speaking groups along the coastlines were more intermixed.[8][11]

Further DNA analysis has taken research into new directions, as more Homo erectus races or subspecies have been discovered since the late 20th century. Based on his genetic studies of the Denisova hominin, an ancient human species discovered in 2010, Svante Pääbo claims that ancient human ancestors of the Melanesians interbred in Asia with these humans. He has found that people of New Guinea share 4%–7% of their genome with the Denisovans, indicating this exchange.[13] The Denisovans are considered cousin to the Neanderthals. Both groups are now understood to have migrated out of Africa, with the Neanderthals going into Europe, and the Denisovans heading east about 400,000 years ago. This is based on genetic evidence from a fossil found in Siberia. The evidence from Melanesia suggests their territory extended into southeast Asia, where ancestors of the Melanesians developed.[13]

Melanesians of some islands are one of the few non-European peoples, and the only dark-skinned group of people outside Australia, known to have blond hair. The blond trait developed via the TYRP1 gene, which is not the same gene that causes blondness in European blonds.[14]

History of classification

[edit]Early European explorers noted the physical differences among groups of Pacific Islanders. In 1756 Charles de Brosses theorized that there was an 'old black race' in the Pacific who were conquered or defeated by the peoples of what is now called Polynesia, whom he distinguished as having lighter skin.[15]: 189–190 By 1825 Jean Baptiste Bory de Saint-Vincent developed a more elaborate, 15-race model of human diversity.[16] He described the inhabitants of modern-day Melanesia as Mélaniens, a distinct racial group from the Australian and Neptunian (i.e. Polynesian) races surrounding them.[15]: 178

In 1832 Dumont D'Urville expanded and simplified much of this earlier work. He classified the peoples of Oceania into four racial groups: Malayans, Polynesians, Micronesians, and Melanesians.[17]: 165 D'Urville's model differed from that of Bory de Saint-Vincent in referring to 'Melanesians' rather than 'Mélaniens.' He derived the name Melanesia from Greek μέλας, black, and νῆσος, island, to mean "islands of black people".

Bory de Saint-Vincent had distinguished Mélaniens from the indigenous Australians. Dumont D'Urville combined the two peoples into one group.

Soares et al. (2008) have argued for an older pre-Holocene Sundaland origin in Island Southeast Asia (ISEA) based on mitochondrial DNA.[18] The "out of Taiwan model" was challenged by a study from Leeds University and published in Molecular Biology and Evolution. Examination of mitochondrial DNA lineages shows that they have been evolving in ISEA for longer than previously believed. Ancestors of the Polynesians arrived in the Bismarck Archipelago of Papua New Guinea at least 6,000 to 8,000 years ago.[19]

Paternal Y chromosome analysis by Kayser et al. (2000) also showed that Polynesians have significant Melanesian genetic admixture.[20] A follow-up study by Kayser et al. (2008) discovered that only 21% of the Polynesian autosomal gene pool is of Melanesian origin, with the rest (79%) being of East Asian origin.[21] A study by Friedlaender et al. (2008) confirmed that Polynesians are closer genetically to Micronesians, Taiwanese Aborigines, and East Asians, than to Melanesians. The study concluded that Polynesians moved through Melanesia fairly rapidly, allowing only limited admixture between Austronesians and Melanesians.[22] Thus, the high frequencies of B4a1a1 are the result of drift and represent the descendants of a very few successful East Asian females.[23]

Austronesian languages and cultural traits

[edit]Austronesian languages and cultural traits were introduced along the north and south-east coasts of New Guinea and in some of the islands north and east of New Guinea by migrating Austronesians, probably starting over 3,500 years ago.[11] This was followed by long periods of interaction that resulted in many complex changes in genetics, languages, and culture.[24]

It was once postulated that from this area a very small group of people (speaking an Austronesian language) departed to the east and became the forebears of the Polynesian people.[25] This theory was, however, contradicted by a study published by Temple University finding that Polynesians and Micronesians have little genetic relation to Melanesians; instead, they found significant distinctions between groups living within the Melanesian islands.[26][11]

Genetic links have been identified between the Oceanic peoples. Polynesians are dominated by a type of macro-haplogroup C y-DNA, which is a minority lineage in Melanesia, and have a very low frequency of the dominant Melanesian y-DNA K2b1. A significant minority of them also belongs to the typical East Asian male Haplogroup O-M175.[20]

Some recent studies suggest that all humans outside of Sub-Saharan Africa have inherited some genes from Neanderthals, and that Melanesians are the only known modern humans whose prehistoric ancestors interbred with the Denisova hominin, sharing 4%–6% of their genome with this ancient cousin of the Neanderthal.[13]

Incidence of blond hair in Melanesia

[edit]

Most people with blond hair are of Northern European ethno-racial origins. It evolved independently in Melanesia,[27][28] where Melanesians of some islands (along with some indigenous Australians) are one of a few non-European ethnic groups who have blond hair. This has been traced to an allele of TYRP1 unique to these people, and is not the same gene that causes blond hair in the Northern European region. As with blond hair that arose in Northern Europe, incidence of blondness is more common in children than in adults, with hair tending to darken as the individual matures.

Melanesian areas of Oceania

[edit]

The predominantly Melanesian areas of Oceania include New Guinea and surrounding islands, the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu and Fiji[citation needed]. New Caledonia and nearby Loyalty Islands for most of their history have had a majority Melanesian population, but the proportion has dropped to 43% in the face of modern immigration.[29]

The largest and most populous Melanesian country is Papua New Guinea. The largest city in Melanesia is Port Moresby in Papua New Guinea with about 318,000 people, mostly of Melanesian ancestry.[30] The western half of New Guinea is part of Indonesia and is predominantly inhabited by indigenous Papuans, with a significant minority of settlers from other parts of Indonesia.

In Australia, the total population of Torres Strait Islanders, a Melanesian people, as of 30 June 2016[update], was about 38,700 identifying as being of Torres Strait Islander origin only, and 32,200 of both Aboriginal Australian and Torres Strait Islander origin (a total of 70,900).[31]

See also

[edit]- List of ethnic groups of West Papua Province

- List of ethnic groups of Southwest Papua Province

- Aeta people – Ethnic group of the Philippines

- Alfur people – Broad term for peoples of Southeast Asia

- Austronesian peoples – Speakers of Austronesian languages

- Malagasy people – Ethnic groups from Madagascar

- Micronesians – Ethnic groups of Austronesian peoples

- Negrito – Set of ethnic groups in Southeast Asia and Andaman islands

- Ni-Vanuatu – Melanesian ethnic groups native to the island country of Vanuatu

- Oceania – Geographical region in the Pacific Ocean

- Indigenous people of New Guinea – Melanesian inhabitants of New Guinea

- Polynesians – Austronesian ethnolinguistic group

- Sundaland – Biogeographic region of Southeast Asia

- Torres Strait Islanders – One of the two categories of Indigenous Australians

References

[edit]- ^ Keesing, Roger M.; Kahn, Miriam. "Melanesian culture". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

Melanesian culture, the beliefs and practices of the indigenous peoples of the ethnogeographic group of Pacific Islands known as Melanesia. From northwest to southeast, the islands form an arc that begins with New Guinea (the western half of which is called Papua and is part of Indonesia, and the eastern half of which comprises the independent country of Papua New Guinea) and continues through the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu (formerly New Hebrides), New Caledonia, Fiji, and numerous smaller islands.

- ^ Dunn, Michael, Angela Terrill, Ger Reesink, Robert A. Foley, Stephen C. Levinson (2004). "Structural Phylogenetics and the Reconstruction of Ancient Language History". Science. 309 (5743): 2072–2075. Bibcode:2005Sci...309.2072D. doi:10.1126/science.1114615. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0013-1B84-E. PMID 16179483. S2CID 2963726.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Taufik, Leonard; Teixeira, João C.; Llamas, Bastien; Sudoyo, Herawati; Tobler, Raymond; Purnomo, Gludhug A. (December 2022). "Human Genetic Research in Wallacea and Sahul: Recent Findings and Future Prospects". Genes. 13 (12): 2373. doi:10.3390/genes13122373. ISSN 2073-4425. PMC 9778601. PMID 36553640.

- ^ Yang, Melinda A. (6 January 2022). "A genetic history of migration, diversification, and admixture in Asia". Human Population Genetics and Genomics. 2 (1): 1–32. doi:10.47248/hpgg2202010001. ISSN 2770-5005.

- ^ a b Vallini, Leonardo; Marciani, Giulia; Aneli, Serena; Bortolini, Eugenio; Benazzi, Stefano; Pievani, Telmo; Pagani, Luca (10 April 2022). "Genetics and Material Culture Support Repeated Expansions into Paleolithic Eurasia from a Population Hub Out of Africa". Genome Biology and Evolution. 14 (4). doi:10.1093/gbe/evac045. ISSN 1759-6653. PMC 9021735. PMID 35445261.

- ^ Pedro, Nicole; Brucato, Nicolas; Fernandes, Veronica; André, Mathilde; Saag, Lauri; Pomat, William; Besse, Céline; Boland, Anne; Deleuze, Jean-François; Clarkson, Chris; Sudoyo, Herawati; Metspalu, Mait; Stoneking, Mark; Cox, Murray P.; Leavesley, Matthew; Pereira, Luisa; Ricaut, François-Xavier (October 2020). "Papuan mitochondrial genomes and the settlement of Sahul". Journal of Human Genetics. 65 (10): 875–887. doi:10.1038/s10038-020-0781-3. PMC 7449881. PMID 32483274.

- ^ Dunn, Michael, Angela Terrill, Ger Reesink, Robert A. Foley, Stephen C. Levinson (2005). "Structural Phylogenetics and the Reconstruction of Ancient Language History". Science. 309 (5743): 2072–2075. Bibcode:2005Sci...309.2072D. doi:10.1126/science.1114615. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0013-1B84-E. PMID 16179483. S2CID 2963726.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c "Genome Scans Show Polynesians Have Little Genetic Relationship to Melanesians", Press Release, Temple University, 17 January 2008, accessed 19 July 2015

- ^ Spriggs, Matthew (1997). The Island Melanesians. Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-16727-3.

- ^ Kayser, Manfred, Silke Brauer, Gunter Weiss, Peter A. Underhill, Lutz Rower, Wulf Schiefenhövel and Mark Stoneking (2000). "The Melanesian Origin of Polynesian Y chromosomes". Current Biology. 10 (20): 1237–1246. Bibcode:2000CBio...10.1237K. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00734-X. PMID 11069104.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f Friedlaender J, Friedlaender FR, Reed FA, Kidd KK, Kidd JR (18 January 2008). "The Genetic Structure of Pacific Islanders". PLOS Genetics. 4 (3): e19. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0040019. PMC 2211537. PMID 18208337.

- ^ Jinam, Timothy A.; Phipps, Maude E.; Aghakhanian, Farhang; Majumder, Partha P.; Datar, Francisco; Stoneking, Mark; Sawai, Hiromi; Nishida, Nao; Tokunaga, Katsushi; Kawamura, Shoji; Omoto, Keiichi; Saitou, Naruya (August 2017). "Discerning the Origins of the Negritos, First Sundaland People: Deep Divergence and Archaic Admixture". Genome Biology and Evolution. 9 (8): 2013–2022. doi:10.1093/gbe/evx118. PMC 5597900. PMID 28854687.

- ^ a b c Carl Zimmer (22 December 2010). "Denisovans Were Neanderthals' Cousins, DNA Analysis Reveals". NYTimes.com. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ Kenny, Eimear E.; Timpson, Nicholas J. (4 May 2012). "Melanesian Blond Hair Is Caused by an Amino Acid Change in TYRP1". Science. 336 (6081): 554. Bibcode:2012Sci...336..554K. doi:10.1126/science.1217849. PMC 3481182. PMID 22556244.

- ^ a b Tcherkézoff, Serge (2003). "A Long and Unfortunate Voyage Toward the 'Invention' of the Melanesia/Polynesia Distinction 1595–1832". Journal of Pacific History. 38 (2): 175–196. doi:10.1080/0022334032000120521. S2CID 219625326.

- ^ "MAPS AND NOTES to illustrate the history of the European "invention" of the Melanesia / Polynesia distinction". Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ^ Durmont D'Urville, Jules-Sébastian-César (2003). "On The Islands of the Great Ocean". Journal of Pacific History. 38 (2): 163–174. doi:10.1080/0022334032000120512. S2CID 162374626.

- ^ Martin Richards. "Climate Change and Postglacial Human Dispersals in Southeast Asia". Oxford Journals. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- ^ Bhanoo, Sindya N. (7 February 2011). "DNA Sheds New Light on Polynesian Migration (Published 2011)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 April 2023.

- ^ a b Kayser, M.; Brauer, S.; Weiss, G.; Underhill, P.A.; Roewer, L.; Schiefenhövel, W.; Stoneking, M. (2000). "Melanesian origin of Polynesian Y chromosomes". Current Biology. 10 (20): 1237–1246. Bibcode:2000CBio...10.1237K. doi:10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00734-x. PMID 11069104. See also correction in: Current Biology, vol. 11, no. 2, pages 141–142 (23 Jan 2001).

- ^ Kayser, Manfred; Lao, Oscar; Saar, Kathrin; Brauer, Silke; Wang, Xingyu; Nürnberg, Peter; Trent, Ronald J.; Stoneking, Mark (2008). "Genome-wide analysis indicates more Asian than Melanesian ancestry of Polynesians". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 82 (1): 194–198. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.09.010. PMC 2253960. PMID 18179899.

- ^ Friedlaender, Jonathan S.; Friedlaender, Françoise R.; Reed, Floyd A.; Kidd, Kenneth K.; Kidd, Judith R.; Chambers, Geoffrey K.; Lea, Rodney A.; et al. (2008). "The genetic structure of Pacific Islanders". PLOS Genetics. 4 (1): e19. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0040019. PMC 2211537. PMID 18208337.

- ^ Assessing Y-chromosome Variation in the South Pacific Using Newly Detected, by Krista Erin Latham [1] Archived 13 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Spriggs, Matthew (1997). The Island Melanesians. Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-16727-3.

- ^ Kayser, Manfred, Silke Brauer, Gunter Weiss, Peter A. Underhill, Lutz Rower, Wulf Schiefenhövel and Mark Stoneking (2000). "The Melanesian Origin of Polynesian Y chromosomes". Current Biology. 10 (20): 1237–1246. Bibcode:2000CBio...10.1237K. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00734-X. PMID 11069104.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Friedlaender, Jonathan (17 January 2008). "Genome scan shows Polynesians have little genetic relationship to Melanesians" (Press release). Temple University.

- ^ Sindya N. Bhanoo (3 May 2012). "Another Genetic Quirk of the Solomon Islands: Blond Hair". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ^ Kenny, Eimear E; Timpson, Nicholas J; Sikora, Martin; Yee, Muh-Ching; Estrada, Andres Moreno; Eng, Celeste; Huntsman, Scott; Burchard, Esteban González; Stoneking, Mark; Bustamante, Carlos D; Myles, Sean M (4 May 2012). "Melanesians blond hair is caused by an amino acid change in TYRP1". Science. 336 (6081): 554. Bibcode:2012Sci...336..554K. doi:10.1126/science.1217849. PMC 3481182. PMID 22556244.

- ^ "Synthèse N°35 – Recensement de la population 2014" (pdf). Nouméa, Nouvelle Calédonie: Institut de la Statistique et des Études Économiques (ISEE). 26 August 2014. p. 3. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- ^ "About PNG". Canberra, Australia: High Commission of the Independent State of Papua New Guinea. Archived from the original on 9 August 2016. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- ^ "3238.0.55.001 - Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, June 2016". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 18 September 2018. Retrieved 1 January 2020.