Yenish people

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in German. (June 2024) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

| |

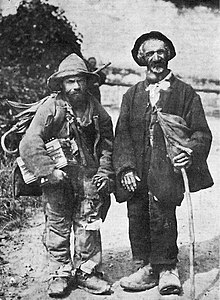

Two Yenish in Muotathal, Switzerland, c. 1890 | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 700,000[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Germany | 200,000[1] |

| Switzerland | 30,000[2] |

| Languages | |

| Yenish, German (Swiss German, Bavarian), French, DGS, DSGS, ÖGS, LSF | |

The Yenish (German: Jenische; French: Yéniche, Taïtch) are an itinerant group in Western Europe who live mostly in Germany, Austria, Switzerland,[3] Luxembourg, Belgium, and parts of France, roughly centered on the Rhineland. A number of theories for the group's origins have been proposed, notingly that the Yenish descended from members of the marginalized and vagrant poor classes of society of the early modern period,including persecuted Ashkenazi jews and gypsies, before emerging as a distinct group by the early 19th century.[4][5] Most of the Yenish became sedentary in the course of the mid-19th to 20th centuries.

The language of the Yenishes, called Yenish, has a grammatical syntax borrowed from the German language and its vocabulary is a mixture of Yiddish, Hebrew and German with some French and Romani terms.[6]

The origin of Yenish peoples is unclear but it would be linked to a gradual interbreeding over the centuries between itinerant German and Ashkenazi Jewish populations, then the integration of certain members of the Gypsy communities: indeed, according to Yaron Matras of the University of Manchester, the Yenish community has, over the centuries, integrated members of minority communities such as Gypsies and Jews who, for one reason or another, left their own communities.[7] This hypothesis is shared by Rémy Welschinger, who specifies that, due to the various wars and numerous food shortages, Jews and Yenishes were forced to live marginally by exercising professions which required great mobility and that the two peoples were able to settle and their languages to mix.[8] In this hypothesis, the Yenish language would mainly come from the mixture of Rotwelsch, the language of the marginalized of Germanic origin, and Yiddish and Hebrew, the languages of the Ashkenazi Jews, when the poor and marginalized itinerant German populations absorbed, notably via mixed unions, the Jews rejected on the road, following the persecutions carried out against them at the time. According to Sandrine Szwarc also raises the hypothesis that the Yenishes are, at least for certain families, descendants of Ashkenazi crypto-Jews.[9]

Interestingly, according to the encyclopedia of Hebrew languages and linguistics, jenisch "words of Hebrew origin, such as laf ‘no’ (= לאו lav) and Schuck ‘market’ (= שוק šuq), entered Jenisch with the Ashkenazi pronunciation employed when Hebrew words were integrated in the Judeo-German speech of German Jews",[10] that is to say before its modification in contact with Slavic languages.

Name

[edit]The Yenish people as a distinct group, as opposed to the generic class of vagrants of the early modern period, emerged towards the end of the 18th century. The adjective jenisch is first recorded in the early 18th century in the sense of "cant, argot".[a] A self-designation Jauner is recorded in 1793.[b] Jenisch remained strictly an adjective that refers to the language, not the people, until the first half of the 19th century. Jean Paul (1801) glosses jänische Sprache ("Yenish language") with so nennt man in Schwaben die aus fast allen Sprachen zusammengeschleppte Spitzbubensprache ("this is the term used in Swabia for an argot used by rogues which has been cobbled together from all sorts of languages").[12] An anonymous author in 1810 argues that Jauner is a deprecating term, equivalent to card sharp, and that the proper designation for the people should be jenische Gasche, Gasche being a slang word derived from the Romani term for 'non-Romani'.[13][14]

Germany

[edit]Many Yenish people in Germany became sedentary in the second half of the 19th century. The Kingdom of Prussia in 1842 introduced a law forcing municipalities to provide social welfare to permanent residents without citizenship. As a consequence, there were attempts to prevent Yenish people from taking permanent residence.[15] Recently established settlements of Yenish, Sinti, and Roma, dubbed "gypsy colonies" (Zigeunerkolonien), were discouraged and attempts were made to incite the settlers to move away, in the form of various forms of harassment, and in some cases physical attacks.[16] By the late 19th century, many recently sedentary Yenish were nevertheless integrated into local populations, gradually moving away from their tradition of endogamy thus being absorbed into the general German population. Those Yenish who did not become sedentary by the late 19th century took to living in trailers.

The persecution of Romani people under Nazi Germany beginning in 1933 was directed not exclusively against the Romani people but also targeted "vagrants who travel around after the manner of the gypsies" ("nach Zigeunerart umherziehende Landfahrer"), which included the Yenish and people without permanent residence in general.[17][18] Travellers were scheduled for internment in Buchenwald, Dachau, Sachsenhausen and Neuengamme.[19] Yenish families began to be registered in a Landfahrersippenarchiv ('archive of travelling families'), but this effort was incomplete by the end of World War II.[20] It appears that only very limited numbers of Yenish (compared with the number of Romani victims) were actually deported: five Yenish individuals are on record as having been deported from Cologne,[21] and a total of 279 woonwagenbewoners ('caravan dwellers') are known to have been deported from the Netherlands in 1944.[22] Lewy (2001) has discovered one case of the deportation of a Yenish woman in 1939.[23] The Yenish people are mentioned as a persecuted group in the text of the 2012 Memorial to the Sinti and Roma Victims of National Socialism in Berlin.[24]

Switzerland

[edit]In 2001, Swiss National Councillor Remo Galli, as speaker of the foundation Zukunft für Schweizer Fahrende, reported an estimate of 35,000 "travellers" (Fahrende, a term combining Sinti, Roma and Yenish), both sedentary and non-sedentary, in Switzerland, among them an estimated 20,000 Yenish people.[25] Mariella Mehr had already claimed in 1979 that there were "about 20,000 Yenish", among whom only "a handful of families who are still travelling".[26]

From the 1920s until the 1970s, the Swiss government had a semi-official policy of institutionalizing Yenish parents as mentally ill and having their children adopted by members of the sedentary Swiss population. The name of this program was Kinder der Landstrasse ('Children of the Road'). The separation of children was justified as the Yenish being a 'criminal milieu' of 'homelessness and vagrancy' was later criticized as a violation of the fundamental rights of the Yenishe to family life, with children separated from parents by force without due criminal procedure, and resulting in many of the children suffering an ordeal of successive foster homes and orphanages.[27] In all, 590 children were taken from their parents and institutionalized in orphanages, mental institutions, and even prisons. Child removals peaked in the 1930s to 1940s, in the years leading up to and during World War II. After public criticism in 1972, the program was discontinued in 1973.[28]

An organisation for the political representation of travellers (Yenish as well as Sinti and Roma) was founded in 1975, named Radgenossenschaft der Landstrasse ("Wheel Cooperative of the Road"). The Swiss federal authorities have officially recognized the "Swiss Yenish and Sinti" as a "national minority".[29] With the ratification of the European language charter in 1997, Switzerland has given the status of a "territorial non-tied language" to the Yenish language.

Austria

[edit]Around 1800, a group of Yenish settled in Loosdorf near Melk, and since then a language island of Yenish has existed there.[30] In November 2021, on the initiative of linguist Heidi Schleich and now chairman Marco Buckovez, the association Jenische in Österreich (Yenish in Austria)[31] was founded with headquarters in Innsbruck. As part of a meeting with the ethnic group spokespersons of the parliamentary parties, the association submitted a request for recognition in accordance with the Ethnic Groups Act on 23 March 2022.[32]

France

[edit]While there are references to Yenish people in France, there are no reported figures.[33] Alain Reyniers wrote in a 1991 article in the journal Etudes Tsiganes that the Yenish "probably form the largest group of travellers in France today".[34]

Yenish organisations

[edit]- Radgenossenschaft der Landstrasse (Switzerland)

- Jenischer Kulturverband (Austria)

- Jenischer Bund in Deutschland und Europa (Germany)

- Woonwagenbelangen Nederland (Netherlands)

Film and television

[edit]- 1957: Es geschah am hellichten Tag

- 1979: Das gefrorene Herz

- 1992: Kinder der Landstrasse

- 2008: Hunkeler macht Sachen

- 2016: Fog in August based on the 2008 book of the same name

- 2017: Dove cadono le ombre

- 2023: Ruäch — eine Reise ins jenische Europa

- 2023: Lubo

Notable people

[edit]- Mariella Mehr (1947–2022), notable for documenting the plight she suffered under the Kinder der Landstrasse project in the 1970s, contributing to its discontinuation

- Stephan Eicher (b. 1960), Swiss musician, Yenish on his father's side

- Oliver Kayser, Luxembourgish musician and variété performer

- Rafael van der Vaart (b. 1983), Dutch footballer

- Pierre Bodein (b. 1947), French spree killer

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ The 1714 reference refers to the Rotwelsch cant, not its speakers, with no implication of an itinerant lifestyle.[11]

- ^ Jauner is reported as a Rotwelsch term for vagrants in Swabia. Johann Ulrich Schöll, Abriß des Jauner- und Bettelwesens in Schwaben nach Akten und andern sichern Quellen von dem Verfasser des Konstanzer Hans. Stuttgart 1793. The author of the 1793 work identifies the vagrant populations of criminals as a recent phenomenon, originally due to vagrant soldiers in the Thirty Years' War and reinforced by later wars.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Murphy, David (25 July 2017). "Ethnic Minorities in Europe; the Yenish (Yeniche) People". Traveller's Voice. Archived from the original on 2024-07-07. Retrieved 7 November 2023.

- ^ Vuilleumier, Marie (24 September 2019). "Switzerland's nomads face an endangered way of life". SWI swissinfo. Archived from the original on 7 November 2023. Retrieved 7 November 2023.

- ^ Ermolenko & Turchyn 2021, p. 27.

- ^

- Lucassen, Leo (1993). "A Blind Spot: Migratory and Travelling Groups in Western European Historiography". International Review of Social History. 38 (2): 209–223. doi:10.1017/S0020859000111940.

- Lucassen, Leo; Willems, Wim; Cottaar, Annemarie (1998). Gypsies and Other Itinerant Groups: A Socio-Historical Approach. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-68241-8.

- "Jenische. Zur Archäologie einer verdrängten Kultur" [Yenish. On the archaeology of a repressed culture]. Beiträge zur Volkskunde in Baden-Württemberg (in German). 8: 63–95. 1993.

- ^ Seidenspinner, Wolfgang (1985). "Herrenloses Gesindel. Armut und vagierende Unterschichten im 18. Jahrhundert" [Masterless Rabble: Poverty and Wandering Underclasses in the 18th Century]. Zeitschrift für die Geschichte des Oberrheins (in German). 133: 381–386.

- ^ Glorice Weinstein, le yeniche langue des gitans suisses, 2013

- ^ http://languagecontact.humanities.manchester.ac.uk/McrLC/casestudies/YM_Jenisch.html

- ^ Rémy Welschinger, Vanniers (Yeniches) d'Alsace, Nomades blonds du Ried, L'Harmattan, 2013

- ^ Sandrine Szwarc, Le yéniche, une langue méconnue à l’histoire fascinante, L'Eclaireur, 2022

- ^ ENCYCLOPEDIA OF HEBREW LANGUAGE AND LINGUISTICS Volume 2 G–O, 2013

- ^ Kluge, Friedrich (1987) [1901]. Rotwelsch. Quellen und Wortschatz der Gaunersprache und der verwandten Geheimsprachen [Rotwelsch. Sources and vocabulary of the thieves’ language and related secret languages] (in German). Strasbourg. p. 175f.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Paul, Jean (1801). Komischer Anhang zum Titan [Funny appendix to Titan] (in German). p. 108.

- ^ Anonymous (24 August 1810). "Die Jauner-Sprache" [The Jauner language]. Der Erzähler (in German). No. 34. p. 157f.

- ^ Matras, Yaron (1998). "The Romani element in German secret languages: Jenisch and Rotwelsch". In Matras, Yaron (ed.). The Romani Element in Non-Standard Speech. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. pp. 193–230.

Gasche is itself a Rotwelsch term, derived from the Romani term gadže 'non-gypsies'.

- ^ Verordnung über die Aufnahme neu anziehender Personen vom 31. Dezember 1842, Neue Sammlung, 6. Abt., S. 253–254; Verordnung über die Verpflichtung zur Armenpflege vom 31. Dezember 1842, ebenda, S. 255–258; Verordnung über Erwerbung und Verlust der Eigenschaft als Preußischer Untertan vom 31. Dezember 1842, in: ebenda, 259–261.

- ^ Opfermann, Ulrich [in German] (1995). ""Mäckeser". Zur Geschichte der Fahrenden im Oberbergischen im 18. und 19. Jahrhundert" ["Mäckeser". On the history of the travellers in the Oberberg region in the 18th and 19th centuries]. Beiträge zur Oberbergischen Geschichte (in German). 5. Gummersbach: 116–128.

- ^ Wolfgang Ayaß, "Gemeinschaftsfremde". Quellen zur Verfolgung von "Asozialen" 1933–1945, Koblenz 1998, Nr. 50.

- ^ Ermolenko & Turchyn 2021, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Opfermann, Ulrich [in German] (2010). "Die Jenischen und andere Fahrende. Eine Minderheit begründet sich" [The Yenish and other travellers. A minority is established.]. Jahrbuch für Antisemitismusforschung (in German). 19: 126–150 [148–150].

- ^ Zimmermann, Michael, Rassenutopie und Genozid. Die nationalsozialistische „Lösung der Zigeunerfrage“, Hamburg 1996, S. 153, S. 436. Ulrich Opfermann: Die Jenischen und andere Fahrende. Eine Minderheit begründet sich, in: Jahrbuch für Antisemitismusforschung 19 (2010), S. 126–150; ders., Rezension zu: Andrew d’Arcangelis, Die Jenischen – verfolgt im NS-Staat 1934–1944. Eine sozio-linguistische und historische Studie, Hamburg 2006, in: Historische Literatur, Bd. 6, 2008, H. 2, S. 165–168,

- ^ Michael Zimmermann, Rassenutopie und Genozid. Die nationalsozialistische „Lösung der Zigeunerfrage“, Hamburg 1996, 174; Karola Fings/Frank Sparing, Rassismus – Lager – Völkermord. Die nationalsozialistische Zigeunerverfolgung in Köln, Köln 2005, 211.

- ^ Michael Zimmermann, Rassenutopie und Genozid. Die nationalsozialistische „Lösung der Zigeunerfrage“, Hamburg 1996, 314.

- ^ Lewy, Guenther (2001). "Rückkehr nicht erwünscht". Die Verfolgung der Zigeuner im Dritten Reich ["Return undesirable": The persecution of the Gypsies in the Third Reich] (in German). Munich/Berlin. p. 433.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Vollständiger Text auf den Informationstafeln des Denkmals, Dokumentations- und Kulturzentrum Deutscher Sinti und Roma, Pressemappe, S. 16–20, pdf

- ^ Rahmenkredit Stiftung „Zukunft für Schweizer Fahrende“, in: Nationalrat, Sommersession 2001, Sechste Sitzung, 11. Juni 2001. [1]

- ^ Mehr, Mariella (1979). "Jene, die auf nirgends verbriefte Rechte pochen" [Those who insist on rights that are not enshrined anywhere]. In Zülch, Tilman; Duve, Freimut (eds.). In Auschwitz vergast, bis heute verfolgt. Zur Situation der Roma (Zigeuner) in Deutschland und Europa [Gassed in Auschwitz, persecuted to this day. On the situation of the Roma (Gypsies) in Germany and Europe] (in German). Reinbek. pp. 274–287 [276f.]

eine Handvoll Sippen, die noch reisen würden

[a handful of clans that would still travel] - ^ Huonker, Thomas; Ludi, Regula (2001). Roma, Sinti und Jenische. Schweizerische Zigeunerpolitik zur Zeit des Nationalsozialismus. Beitrag zur Forschung [Roma, Sinti and Yenish. Swiss Gypsy policy during the National Socialist era. Contribution to research] (PDF). Veröffentlichungen der UEK (Report) (in German). Vol. 23. UEK, Swiss Government. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2023.

- ^ Gaillard, Florence (12 December 2007). "Le passé enfin écrit des enfants enlevés en Suisse" [The past finally written of the children abducted in Switzerland]. Le Temps (in French). Geneva. Archived from the original on 19 June 2024., an historical study spanning the years from 1926 to 1973.

- ^ Since autumn 2016, the Swiss federal authorities officially declare: "With the ratification of the Framework Convention of the Council of Europe of 1 February 1995 on the Protection of National Minorities, Switzerland has recognized the Swiss Yenish and Sinti as a national minority—regardless of whether they live travelling or sedentary."[citation needed]

- ^ "Loosdorf: Wo viele noch Jenisch 'baaln'" [Loosdorf: Where many still 'baaln' [speak] Jenisch]. ORF.at (in German). 2 March 2017. Archived from the original on 5 October 2023.

- ^ "Jenische in Österreich - Website des Vereins" [Yenish in Austria - Website of the association] (in German). Archived from the original on 1 February 2022. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ "Offizielles Ersuchen der Jenischen um Anerkennung" [Official request from the Yenish for recognition]. ORF.at (in German). 23 March 2022. Archived from the original on 14 April 2024. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ Bouniot, Sophie (16 May 2007). "Misère et rejet. L'histoire des Yeniches de l'affaire Bodein" [Misery and Rejection. The Story of the Yeniches of the Bodein Affair]. L'Humanité (in French).

En France, on ne connaît pas exactement leur nombre.

[In France, we do not know their exact number.] - ^ Bader, Christian (2007). Yéniches: les derniers nomades d'Europe [Yenish: the last nomads of Europe] (in French). L'Harmattan. ISBN 978-2-296-03675-8.

Ils constituent, aujourd'hui en France, sans doute le groupe le plus volumineux au sein de la communauté des Gens du voyage

[Today in France, they constitute without doubt the largest group within the community of Travellers.]

Works cited

[edit]- Ermolenko, Svetlana; Turchyn, Karina (2021). "Sprachliche Diskriminierung und die Politische Korrektheit in Der Deutschen Sprache" [Linguistic Discrimination and Political Correctness in the German Language]. Philological Treatises (in German). 13 (1): 24–31. doi:10.21272/Ftrk.2021.13(1)-3.

Further reading

[edit]- Becker, Helena Kanyar (2003). Jenische, Sinti und Roma in der Schweiz [Yenish, Sinti and Roma in Switzerland]. Basler Beitrage zur Geschichtswissenschaft (in German). Vol. 176. Basel: Schwabe. ISBN 3-7965-1973-3.

External links

[edit] Media related to Yenish at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Yenish at Wikimedia Commons